Mother Jones; Macmillan; Broadside Books

There is a kind of genius in writing the savage review. Sometimes they become assessments of an artist that endure long after the works critiqued have faded from popular memory. The former New York Times chief book critic Michiko Kakutani (once called “the Queen of Mean”) described The Discomfort Zone, a memoir by Jonathan Franzen, as “an odious portrait of the artist as a young jackass: petulant, pompous, obsessive, selfish and overwhelmingly self-absorbed.” The great British theater critic and writer Kenneth Tynan said the rugged and proudly unsophisticated actor Anthony Quinn, “always acts as if he were wearing a suit for the first time.” And then there is Times movie critic A.O. Scott writing about Transformers: Dark of the Moon in 2011: “I can’t decide if this movie is so spectacularly, breathtakingly dumb as to induce stupidity in anyone who watches, or so brutally brilliant that it disarms all reason. What’s the difference?”

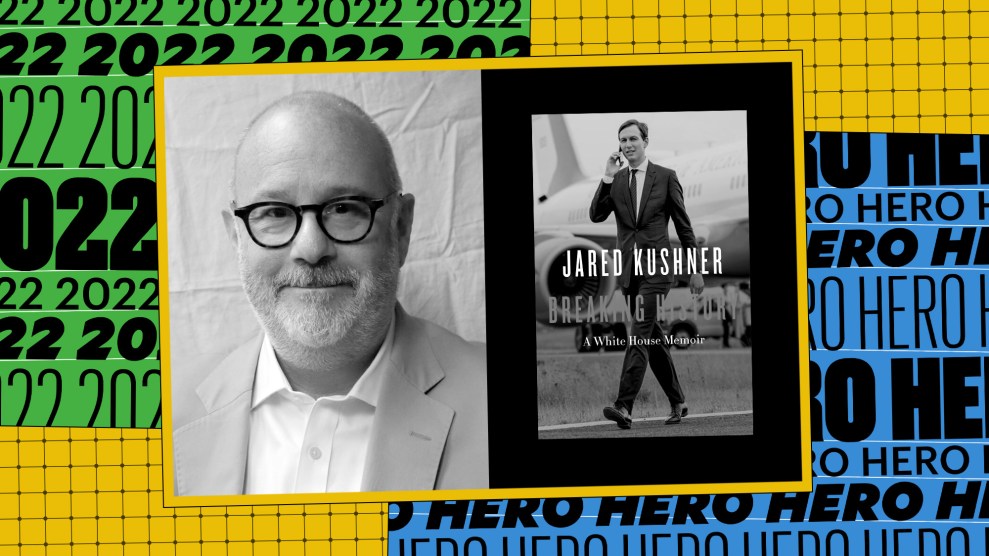

Fast forward to 2022 for an addition to this distinguished group. When the odious son-in-law of a vile president pens his reflections on his time in public service, someone must step forward. We are lucky it was Dwight Garner. He read the 492 pages of Breaking History: A White House Memoir. And then he wrote about it so decisively that none of us have to endure the slog.

As anyone who has paid the most remote attention to the onslaught of books by former Trump enablers knows, the appearance of this book was notable mostly because Kushner was the most insidery of insiders: a close adviser on weighty matters—supply chains! Mid-East Peace!— and the husband of the president’s favorite child. Plus, he went to Harvard! Surely there would be important insights on power, thoughtful policy reflections, and maybe even some yummy nuggets from chez Kushner.

Instead, as Garner so elegantly put it:

This book is like a tour of a once majestic 18th-century wooden house, now burned to its foundations, that focuses solely on, and rejoices in, what’s left amid the ashes: the two singed bathtubs, the gravel driveway and the mailbox. Kushner’s fealty to Trump remains absolute. Reading this book reminded me of watching a cat lick a dog’s eye goo.

What is so genius about this image? The answer, as with nearly all great brief sentences, is both literal and symbolic. Who among us has had the distinct pleasure of actually watching a cat lick a dog’s eye goo? As the proud owner, for many years, of three cats and one dog, this moment has eluded me. How preternaturally chill (or ancient) must both animals in this peaceable kingdom be to play their assigned roles? And yet, you can just see it: The sandpaper tongue, the icky ooze slightly hardened. The service of one subordinate but generally pristine beast to its sloppy comrade. Which is, I suppose, where the literal becomes symbolic: the sleek feline Jared eager to attend to his master, performing even the most debased act with submissive eager attention.

But Garner, the consummate professional, knows that literary criticism requires a focus on the elements of the work under consideration. Sharpening his skewer, he sets to work.

- The tone: “college admissions essay. Typical sentence: ‘In an environment of maximum pressure, I learned to ignore the noise and distractions and instead to push for results that would improve lives.’”

- The language: “Every political cliché gets a fresh shampooing.”

- The writer’s self-awareness: “Kushner, poignantly, repeatedly beats his own drum. He recalls every drop of praise he’s ever received; he brings these home and he leaves them on the doorstep. ” (The “poignantly” is worth many bonus points here. )

- The allusions to other works: “If Kushner can recall a professor or a book that influenced him while in Cambridge, he doesn’t say.”

- The character development: “Once in the White House, Kushner became Little Jack Horner, placing a thumb in everyone else’s pie, and he wonders why he was disliked.”

Yes, it would be easy to pluck one of these writerly jewels after another out of this review, but these are just a few to demonstrate the worthiness of Garner’s heroic status. In the end, this review may gain the immortality of Dorothy Parker, writing as the “Constant Reader” in the New Yorker. In her October 12, 1928 review of The House at Pooh Corner, she described her experience of reading the book as one that Garner might relate to over a hundred years later: “Tonstant Weader fwowed up.”

As usual, the staff of Mother Jones is rounding up the heroes and monsters of the past year. Find all of 2o22’s here.