For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

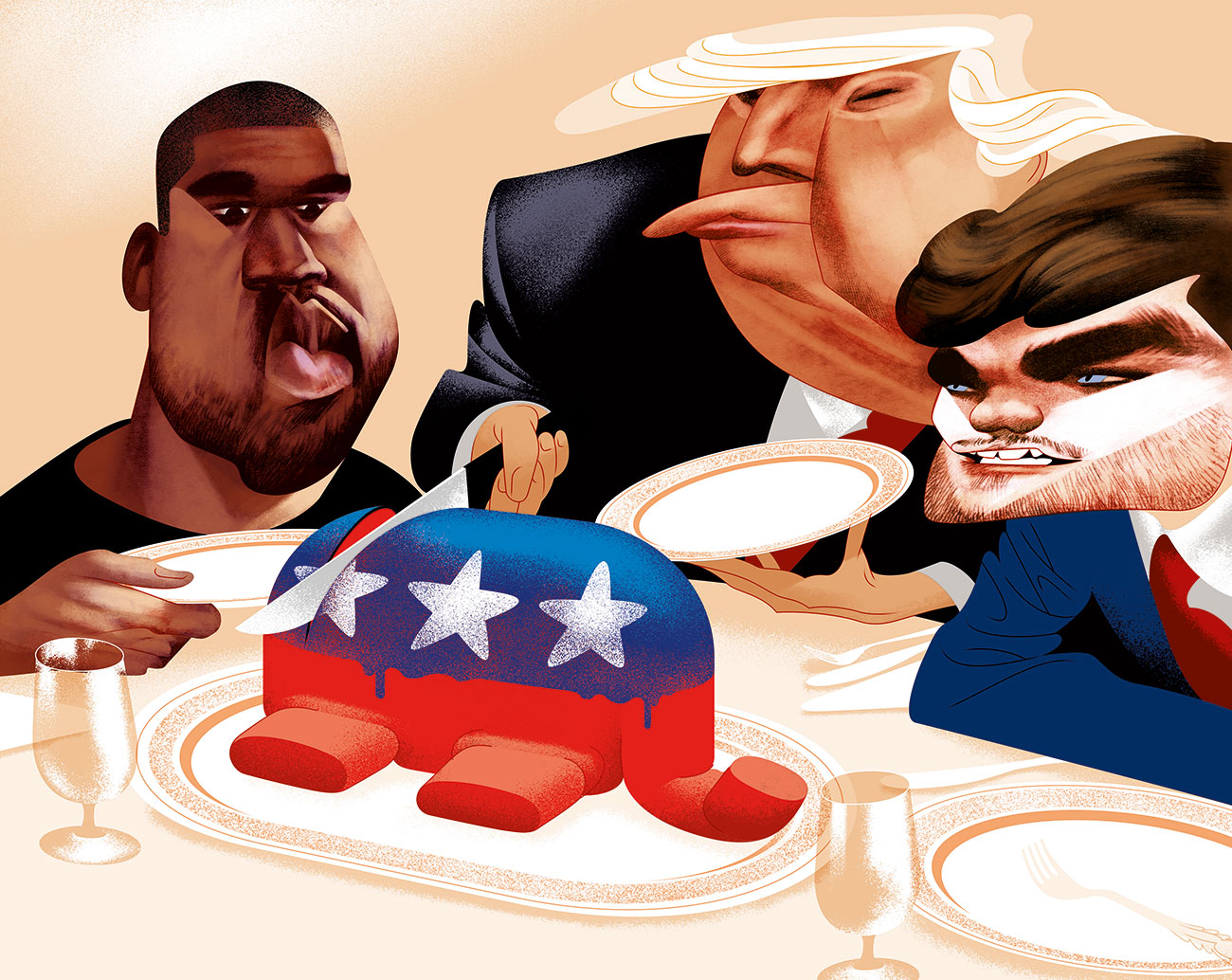

Eight months before the white nationalist figure Nicholas J. Fuentes ignited a political firestorm by dining with Kanye West and Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago, he strode out onstage to a crowd of what he claimed were 1,000 followers, chanting “America First.” Behind a podium, flanked by two American flags and one with that slogan, he hit his standard beats (the nation is in decline, Christ is king) while sprinkling in some extremely troubling riffs, like comparing Vladimir Putin to Hitler—and suggesting the similarity was a “good thing.”

This Marriott conference center worth of Groypers—which Fuentes’ fans call themselves in homage to a right-wing internet frog meme—had gathered in Orlando for the third annual America First Political Action Conference. He was serving as the warmup act for a secret guest of honor: Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.). She didn’t say anything too noteworthy, but her willingness to appear at an event hosted by an openly racist Holocaust denier was a massive victory for his cause. In becoming a member of Congress, Greene had helped bring institutional credibility to fringe and racist conspiracy theories. Now she was doing the same for his brand of white nationalism.

“It was a big deal for her to come out and do that,” Fuentes said, praising Greene after her keynote. “You guys know full well the risk—she put herself out on a limb tonight and we here at AFPAC are grateful.”

“At AFPAC I famously said it would be a small group of highly motivated people who would change the world,” he added. “Here in Orlando, I say we are that group of people…We are going to rule this country.”

The event’s evolution suggests he’s made progress toward that goal. The first one, in February 2020, had no politicians, instead featuring far-right commentator Michelle Malkin and Patrick Casey, a longtime member and leader of the neo-Nazi group Identity Evropa. By 2022, six Republican elected officials spoke, including Greene and Rep. Paul Gosar (R-Ariz.). They appeared alongside explicit white power activists, including Vincent James, a supremacist influencer who used his speaking slot to argue that crime wouldn’t go down until even more Black Americans were in prison; Peter Brimelow, who founded the white supremacist website VDare; and Jared Taylor, founder of American Renaissance, a racist journal.

The logistics of the Orlando conference, like the previous ones, were also designed to accelerate the GOP’s slide toward white nationalism: It was just a 15-minute drive from where the Conservative Political Action Conference, which for decades has drawn the party’s biggest names and thousands of attendees, was taking place the same day. AFPAC started at 9 p.m., after CPAC wrapped, so participants could attend both.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the GOP was pushed right by radio provocateurs like Rush Limbaugh and Fuentes’ hero Pat Buchanan—people who never held elected office but were deeply influential to a radicalizing party and a portent of its Trumpified future. Today, this 24-year-old digital native is doing the same. “My job,” Fuentes explained in a May 2021 livestream, “is to keep pushing things further. We, because nobody else will, need to push the envelope. We’re going to get called racist, sexist, anti-Semitic, bigoted, whatever. When the party is where we are two years later, we’re not going to get the credit for the ideas that become popular. But that’s okay…We are the right-wing flank of the Republican Party.”

I saw how Fuentes makes his pitch on a chilly, damp day in November 2021, when he hosted a rally in front of Gracie Mansion, the official residence of New York City’s mayor. A throng of about 100 intently watched as Fuentes waved a crucifix and railed against local Covid restrictions.

One of Fuentes’ talents is pivoting from any topic to his central beliefs. “It’s not even just about the pandemic,” he exhorted. “Take a look at this city for the past year, ever since George Floyd died… Just like every city in America, the crime is out of control!” Anger over public health measures provided a way to launder more extreme and racist positions—and to tap into his audience’s fears of being left behind.

The crowd—mostly white, male, and under 30—cheered. A handful waved flags, and others, in the organization’s riff on red MAGA hats, wore blue caps reading “America First.” (The slogan, popularized by Woodrow Wilson, was adopted by Buchanan and then by Trump and Fuentes.) “Our quality of life is being destroyed… They want us to live in smaller houses. They want us to eat less food, take up less space, have less health care, have fewer children. And they want us to eat crickets,” Fuentes said, egged on by supportive boos. “I’m not eating any bugs!”

From Father Coughlin to Donald Trump, demagogues have long commingled racist and anti-Semitic appeals with fears of economic decline. Fuentes’ power comes from layering on a generational critique that taps into young people’s apprehension that their prospects are dimming. Decades of wage stagnation, growing income inequality, a housing crisis, and productivity gains flowing mostly to upper management and investors have all led Gen Z to question capitalism. The ranks of democratic socialists have grown as a result, but not every young person is drawn to the left.

Fuentes is one of a few figures on the right who directly speak to new generations anxious about the decline of the middle class and wondering what to do about it. By combining class and economic precarity with white nationalism, Fuentes makes racism even more persuasive to a certain kind of person. This brew has helped fuel his meteoric rise from fringe YouTube star to Mar-a-Lago guest, becoming heir apparent to the American white nationalist throne.

Fuentes is known for his charisma. Unlike some of his right-wing internet peers, like Ben Shapiro and Tim Pool, who speak in monotones and try their hardest to present as intellectuals, Fuentes prefers to grandstand while working to provoke and engage. Another major component of Fuentes’ appeal is that he provides logically consistent, albeit atrocious, answers to the contradictions of modern conservatism. His arguments have a way of ripping open muddled beliefs advanced by mainstream conservatives.

Take their grievance against “woke capitalism”—which really means businesses responding to consumer expectations in a manner that bolsters the bottom line—a complaint that flies in the face of the free-market worship that is core to mainstream figures on the right. Fuentes circumvents this contradiction by just never defending capitalism. Unlike many elected Republicans, he does not argue against diversity while claiming he isn’t racist—he openly argues diversity is bad because of his belief in the inferiority of nonwhite races. The list goes on. If there is a right-wing belief that involves obfuscating an unsavory motivation, Fuentes is open about it. He speaks to the people who don’t mind saying everything out loud.

Nick Fuentes grew up in the relative comfort and stability of a two-parent household in the Chicago suburb of La Grange. He has said that his father, Bill Fuentes, a vice president at a ball bearing manufacturer, is half-Mexican, which Nick sometimes uses to claim he’s not a white supremacist—and sometimes brushes off as distant lineage irrelevant after decades of assimilation. His parents supported Nick as he broadcast racist livestreams from their basement. In one, he said that, growing up, his family avoided Applebee’s and Red Lobster because they were “commonly known as Black fare,” adding that they shared a saying about Olive Garden that contained the n-word. In December 2021, his mother phoned in to his show to speculate on the race of a man who’d opened fire in a mall near her home. “What flavor do you think that shooting was?” Lauren Fuentes asked. “You know what I mean.” Before hanging up, in a laughing moment, she insisted Nick had learned anti-Black prejudice “from your dad.”

Nick entered high school in 2012, where he assembled a roster of activities that suggest a lust for attention and budding oratorical skills. He joined the speech team and Model UN, got elected student body president, and was selected to greet Illinois’ governor during a school visit. Fuentes hosted a campus TV and radio talk show where he discussed his conservative politics—he was “more moderate” then, he would later admit, sometimes describing himself as a former libertarian. Bill Allan, who supervised the school’s television programs, told the Chicago Tribune in 2017 that “none of the stuff he produced was even close to the level he’s at now.”*

The libertarian-to-fascist pathway is well documented, and the seeds of what his politics would become were already present. In a blog post from just after his high school graduation, 17-year-old Fuentes harbors a pessimistic outlook that would lead him to forsake free markets: “My timely birth allowed me to watch on the nightly news the spoils of the American experiment squandered for one final time before the dying gasp of a once exceptional people as the free world and economic abundance of Ronald Reagan was inherited by the lizard people… My generation is the generation of hopelessness.” In a foreshadowing of his turn to Christian theocracy, he promised “to promulgate and preach the good word of the American restoration.”

In that same post, written the day before Trump was formally nominated as the Republicans’ 2016 candidate, Fuentes described his ascent as an opportunity. “Donald Trump has created an opening, we don’t know for how long and we don’t know if it’s big enough, but [it is] an opportunity for the American people to throw off the yolk [sic] of the new age orthodoxy which has enslaved us.”

Fuentes eventually deleted his blog, and began the livestreams that would make him a far-right star from his parents’ home. After enrolling at Boston University, he would broadcast nightly from the dorms. He grew more radical and established a campus reputation as an Islamophobic Trump supporter. He claimed persecution, likening the grief students gave him for wearing a MAGA hat to being discriminated against for being Black or wearing a hijab. When campus conservatives tapped him for an election debate against BU’s student president, Fuentes seized every opportunity to antagonize the audience. After claiming that “multiculturalism is a cancer” and trolling the crowd as “godless hippies,” Fuentes admitted to a student journalist that “it wouldn’t be fun if it wasn’t ugly.” After Trump took office, he told the Boston Globe that “Trump is a rocket ship…And everyone is trying to attach themselves to it.”

While there’s little record of his actions that weekend, Fuentes attended the August 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where Confederate flags and torches were hoisted by neofascists, neo-Nazis, white supremacists, militia members, and other far-right demonstrators—one of whom killed Heather Heyer, a counterprotester, by running her over. A few months before, Fuentes had just 2,000 followers on Twitter. But back on his own campus, he said he faced death threats from other students over his presence in Charlottesville. BU security didn’t respond to a request for comment on his claim, but contemporaneous press coverage repeating it raised his profile. By October, he had amassed 12,000 Twitter followers.

The rally proved to be the terminus point for key figures on the alt-right, leaving prominent white nationalists like Richard Spencer and James Allsup either tied up in litigation or too toxic to generate mass appeal. But it was one of the most important moments in Fuentes’ ascent, helping elevate him just as openings emerged among the fascist-in-a-suit set that he would one day take over. He dropped out of BU days after the rally, citing harassment. But the move had the benefit of freeing him to try his hand as a full-time political influencer. “‘Why don’t you give me just one year to explore this?’” Nick recalled telling his parents in a BBC documentary. “‘If it works out, I’ll keep doing it. If it doesn’t work out, I’ll abandon it.’…And it worked out.”

In his streams, Fuentes seldom mentions intellectual influences, preferring to parse the news and grievances of the moment. While he’s praised Brimelow and Taylor, both in their 70s, he’s most enthusiastic about 84-year-old Pat Buchanan. In 2018, on the far-right former presidential candidate’s birthday, Fuentes dedicated 45 minutes of praise to the “fantastic guy.” Clad in a plaid button-down and blazer, he hailed Buchanan’s books, including Suicide of a Superpower and Death of the West. But Fuentes was particularly excited by a syndicated column Buchanan wrote after Charlottesville, waving what he claimed was a signed copy given to him by a friend.

Buchanan’s piece praises the exploits of Western explorers, endorses their self-conception as “white supremacists” who disregarded the people they encountered and believed “European Man had the right to rule the world,” and embraces their vision of a racial hierarchy. “‘All men are equal’ is an ideological statement. Where is the scientific proof for it?” Fuentes read. “You can’t beat that!” he exclaimed. “When he says something like that, I say, ‘Okay, it’s not unpatriotic to believe this stuff. It’s not nonconservative, neo-Nazi stuff. It’s totally legit.’”

“There’s dumb-guy alt-right stuff and then people who consider themselves conservative intellectuals,” says Joshua Citarella, an artist and internet culture researcher who closely observed Fuentes’ ascent. “He was able to bridge the two.” For the next several years, Fuentes mostly straddled these worlds, appealing to online extremists who craved edginess while also seeking mainstream respectability. He took steps to distance himself from white nationalism and tried to hide his most racist beliefs. But after he was banned from Twitter in July 2021, he lost discipline. That November, after Kyle Rittenhouse was acquitted of killing two people amid racial-justice demonstrations in Wisconsin, Fuentes openly admitted to being racist. Two months later, he used the n-word while streaming. By then, whatever game he’d been trying to play had ended.

In 2019, Fuentes encouraged his fans to swarm political events featuring Donald Trump Jr., Rep. Dan Crenshaw (R-Texas), and Charlie Kirk, whose Turning Point USA student organization brought them and similar speakers to college campuses. Fuentes and his followers dubbed it the Groyper Wars, as they commandeered the Q&A portions of events to draw attention and gain recruits, while bullying Kirk and the like to move further to the right. Crenshaw’s response was unsparing: “I fucking hate Nick Fuentes,” he later told CNN. “He’s one of the worst human beings I’ve ever come across.”

But Kirk has since moved to the right. Last April, he tweeted that there “is an undeniable War on White People in The West,” a position he had previously overtly rejected. Fuentes declared victory, crowing on Telegram that the tweet was “a testament to how thoroughly Groypers have taken over the conversation.”

Like most political figures, Fuentes is prone to hyperbole, but the boast has a grain of truth. Since Fuentes came on the scene, prevailing right-wing attitudes have become more openly vitriolic toward LGBTQ people, and versions of the “white replacement” conspiracy theory have proliferated. That may have been inevitable, given the party’s long-standing trajectory and its embrace of Trump, but Fuentes played a part in generating energy around such positions and demonstrating to GOP gatekeepers that they would play with a new generation.

Through rooting around on social media and local news reports, I was able to find 30-some colleges, from Dartmouth to Old Dominion, where campus conservative or Republican organizations have been taken over by America First–styled groups. The groups’ exact orientation toward Fuentes can be unclear, but they all show varying degrees of sympathy to his brand of politics. At least 25 of those schools show up on a list maintained by something called the College Republican Patriot Coalition, whose website says “one of the primary challenges facing America is the gradual loss of its moral character,” and that it is “impossible to disentangle Christianity not only from American identity, but from Western civilization itself.” Simon Dickerman, a videographer, techie, and former Fuentes employee, has said the coalition is secretly run by Fuentes and America First.

Fuentes’ following and impact are hard to precisely measure. Former allies have alleged the numbers are juiced, but counters on his streams have regularly shown five-figure live audiences. Before he was finally banned from Twitter, Fuentes had nearly 140,000 followers; his Telegram now has more than 50,000.

“Nick Fuentes did not single-handedly cause these shifts in the Republican Party and in conservatism. He was in the right place at the right time,” says Ben Lorber, an analyst with the far-right watchdog group Political Research Associates. “I wouldn’t discount his influence, though, in helping craft a Gen Z conservative counterculture”—one that Lorber says is gaining sway as younger people are hired by lawmakers and work their way up the party. “They might not be writing the GOP national convention speeches and platforms, or leading the Heritage Foundation,” he says, “but they might be interns and young staffers.”

Fuentes, who declined to comment for this article, looked set to exit Trump’s presidency with the wind at his back. He still had his Twitter account, and seemed to maintain ties with the broader conservative apparatus. But his actions on January 6, 2021, risked everything he had built, and threatened to leave him marooned, as Charlottesville did to Richard Spencer three years before. Video footage circulated of Fuentes, yet again in a suit and tie, standing on the steps of the Capitol yelling into a megaphone encouraging people to “keep moving towards” the building and to “break down the barriers and disregard the police.” He would be subpoenaed and interviewed by the House January 6 committee, and the FBI reportedly investigated why he had received $250,000 worth of bitcoin in the days before the riot.

“We’re gonna get to the truth tonight about Nick’s sussy baka behavior,” said a giddy, baby-faced young man wearing a Hawaiian shirt, Harry Potter–like glasses, and a microphone headset, sitting in front of a tapestry of playing cards. Sussy baka is an internet term for “suspicious idiot,” and would be used repeatedly in the ensuing hours. The giddy man, a far-right podcaster and streamer who goes by PPP, was minutes away from hosting Jaden McNeil, Fuentes’ former right-hand man.

McNeil had started a successful Turning Point USA chapter at Kansas State University and eventually trekked to CPAC, where he says he met Fuentes. (Although Fuentes was barred from attending the conference in 2019, he established a tradition of speaking at nearby venues and sometimes hanging around outside CPAC’s doors.) Back home, McNeil started watching Fuentes and ultimately decided to drop out of school, move into Fuentes’ basement, and work full-time for America First.

But by the time he joined PPP’s stream in May 2022, McNeil had become a defector ready to detail their falling-out on livestream, and eager to paint a picture of a mercurial, petulant, and venal leader losing control of his acolytes. McNeil complained that he and other followers had been “brainwashed” and told stories suggesting Fuentes was not as committed to Catholicism as his public persona indicates. “Nick would compare himself to Christ,” Dickerman complained, and McNeil said he hardly ever attended Mass: “I can count on one hand the amount of times that I know he went.”

The two discussed a half-dozen or so former associates who’d also left, and griped that interns and staff had been underpaid or stiffed on promised pay. (In 2020, extremism researcher Megan Squire found Fuentes was pulling in more than $100,000 annually by broadcasting on DLive. Though he was kicked off that platform, he still collects money from his proprietary streaming service, sells merch, and accepts donations.) “He’s a sick person who sees no problem destroying young white men’s lives,” McNeil added, recounting Fuentes’ promise to “rape him in legal fees.” To top off their scorched-earth campaign, they speculated that, after January 6, Fuentes had become an FBI informant and insinuated that he was gay. “For some reason,” McNeil said, the fact that he himself dated women had “always been a weird issue with Nick.”

Observers wondered if followers were stepping away from Fuentes’ extreme brand of white nationalism. But McNeil and Dickerman weren’t manifesting disillusionment with the broader political project. Early in the stream, McNeil said Fuentes’ positions were “the truth,” and when Dickerman criticized Fuentes for praising Hitler, all he had to say was that it wasn’t a “winning strategy.” Instead, they were mad their old boss seemed too maniacal or distracted to properly carry the mantle for white Christian nationalists.

Between the defections and complications from January 6, Fuentes seemed at a low point. But this past November, he thought he had managed to find a way out of his problems through two other guys who were also going through it: Ye and Donald Trump.

After Kanye West began openly trafficking in anti-Semitism—and losing lucrative endorsements—Fuentes says he was asked to run Ye’s ostensible 2024 presidential campaign. Fuentes has described West’s reaching out as a lifeline. “I was doing well in 2020, and after January 6, I lost it all,” he lamented in a November 26 stream just after having dinner with Trump and Ye. “My income went to zero overnight. My best friends betrayed me. I was put on a no-fly list. It really looked like it was over,” Fuentes went on. “Now it looks like we’re finally seeing the light at the end of the tunnel,” he added with a smile. (On January 24, Fuentes’ profile got another boost from another Ye fan when Elon Musk’s Twitter reinstated his profile, seemingly gifting him back a platform that had been pivotal to building his movement. The company reversed the decision the next day.)

Fuentes might have first felt a glow after he and Ye broke bread with Trump at Mar-a-Lago, but it immediately became a harsh national spotlight. Even though Trump appeared to be in a funk, his star power on the wane after many candidates he’d backed lost in November’s midterms, the dinner became the country’s No. 1 political news story. Elected Republicans slammed Fuentes—while attempting to absolve the former president of any fault. Even Marjorie Taylor Greene joined in, claiming she condemned “his racist, anti-semitic ideology,” knocking the guy whose conference she’d not long ago headlined as an “immature young man.”

If extremist members of Congress like Greene are no longer willing to openly associate with Fuentes, there are other groups gladly taking advantage of the ideological space he helped create. The American Populist Union was founded in 2021, filling in a gap Fuentes left as he became more overtly extreme and bigoted. While the organization worked to distance itself from Fuentes personally, according to Amanda Moore, a leftist activist who spent almost a year infiltrating the alt-right, “APU was full of Groypers. They’re what Nick Fuentes was.” At the group’s events, she says she saw members wear blue America First hats and joke he was “their favorite Mexican.” In July 2022, the organization rebranded as American Virtue, likely, according to an analysis Lorber wrote for Political Research Associates, as part of another step in its campaign to achieve “mainstream conservative respectability” and “obscure its widespread association with the Groypers.”

Moore witnessed a similar dynamic with Republicans for National Renewal, which she describes as “the mid 30s, late 20s version of APU and the Groypers.” RNR’s grassroots director, Shane Trejo, is a local Michigan GOP official who used to host a podcast called Blood Soil and Liberty with a member of Identity Evropa. Like Fuentes, RNR has cultivated links with GOP legislators and candidates, most notably claiming to have worked with members of Congress on a failed push to create an America First Caucus that would have featured Gosar, Greene, Texas’ Louie Gohmert, and Alabama’s Barry Moore. Punchbowl News, the first to report on the effort in April 2021, described their planning documents as some of the “most nativist stuff we’ve seen.” Moore recorded Mark Ivanyo, RNR’s executive director, telling a CPAC audience two months before the Punchbowl story to “look forward to the America First Caucus,” saying it had “been a pleasure” to cooperate with Greene and Gosar on the project. A deleted RNR tweet claimed one of the group’s leaders had helped draft the caucus platform.

Fuentes’ charisma and antics have helped him build a personal following. But these developments suggest there will be an America First movement whether or not Fuentes is at the helm, because he has accurately located contemporary problems reshaping youth politics: An increasingly geriatric cohort of political leaders has not adapted to a changed world with fewer opportunities for young people. The buttons Fuentes wants to press in response are often fascistic, racist, and immoral. They are also frequently based on specious premises. But they raise the issue of building a better future for certain young people in a way that can resonate among them.

At the end of November, in a livestream after his dinner with Trump, Fuentes announced he would go on a slight hiatus from his nightly videos. Before closing his opening monologue, he paused to gather his thoughts.

“The last thing I’ll say is this: We really are at a crossroads here,” he said, looking straight into the camera. “It’s drag queens in school. It’s 18-year-olds joining OnlyFans. It’s the filth on TikTok. It’s this country not having a border. It’s the idea that our kids and this generation is never going to own anything. Debt slavery. Never owning a house, never owning a car, never paying off their school. Never making an income to support a family. Not being able to have a family,” Fuentes said, seamlessly blending the fears of a culture war with facts about economic precarity. “The future is so bleak. But that has changed the calculation,” he added. “There is nothing to lose.”

This story has been updated to reflect Twitter’s latest decisions on Fuentes’ account.

Correction: An earlier version misstated Allan’s position at the school.