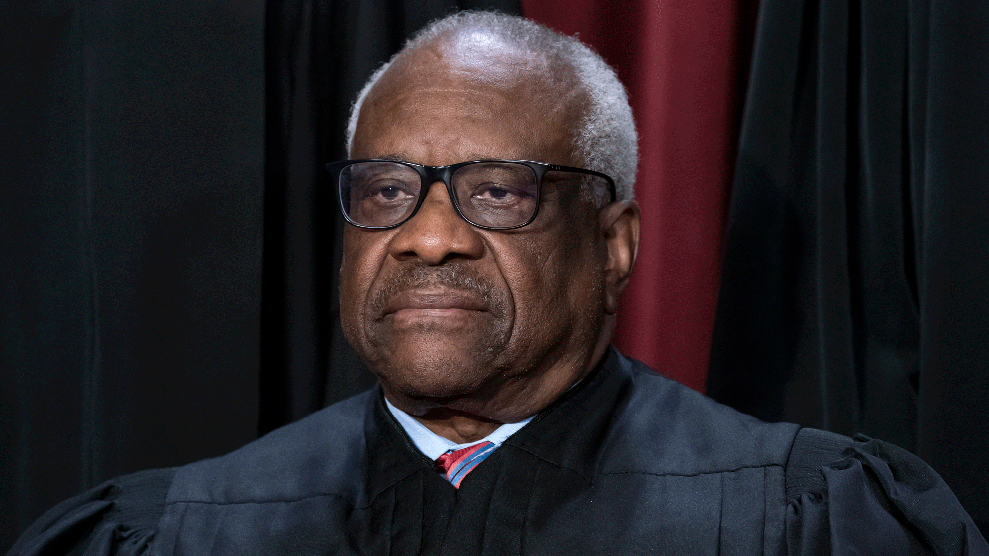

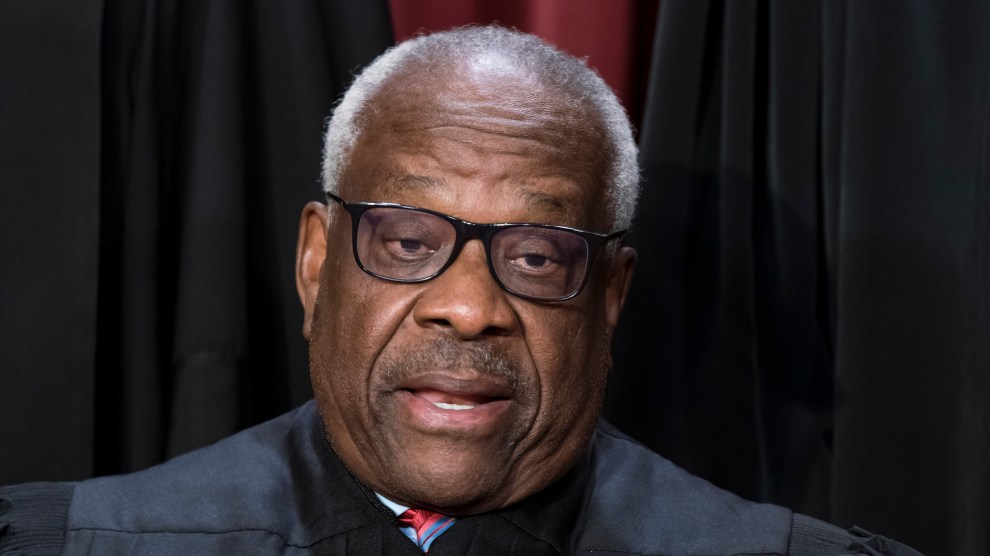

J. Scott Applewhite/AP

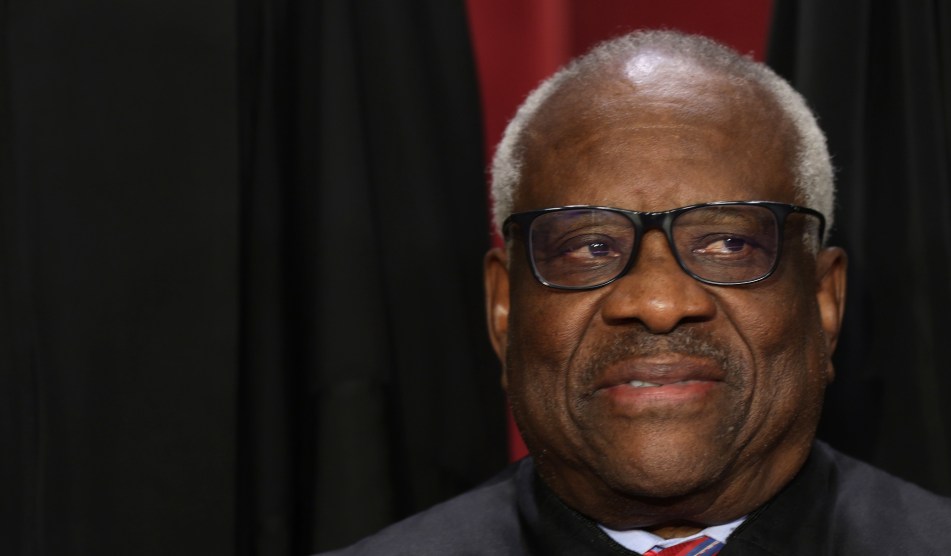

On Thursday, ProPublica dropped a major new story about Clarence Thomas’ relationship with Texas conservative megadonor Harlan Crow. In addition to inviting the Supreme Court justice on expensive vacations on his superyacht, buying Thomas’ mother’s house, and letting her live there rent-free, Crow also spent roughly $100,000 on private-school tuition for Thomas’ great nephew—for whom the justice and his wife, Ginni, served as legal guardians.

Thomas himself did not respond to ProPublica’s queries. But for a sense of what a defense of his failure to disclose these gifts might sound like, look no further than a statement issued by his friend Mark Paoletta, a conservative lawyer who has worked in multiple Republican presidential administrations and is literally the man sitting next to Thomas in the center of a painting Crow once commissioned.

STATEMENT OF MARK PAOLETTA, FRIEND OF JUSTICE THOMAS

The Thomases have rarely spoken publicly about the remarkably generous efforts to help a child in need. They have always respected the privacy of this young man and his family. It is disappointing and painful, but unsurprising…

— Mark Paoletta (@MarkPaoletta) May 4, 2023

The statement walks a tightrope, but not well. It emphasizes that “Justice Thomas and his wife devoted twelve years of their lives to taking in and caring for a beloved child” in the same breath that it emphasizes that the child “was not their own.” It asserts that the tuition “did not constitute a reportable gift” to a dependent, because the Ethics in Government Act “does not include ‘great nephew’” in its list of possible dependents—though, as ProPublica notes, the tuition might more accurately be characterized as a gift to the legal guardians who would otherwise have paid for the child’s education. Paoletta refers to the “personal and financial sacrifices” the Supreme Court justice made to help a relative he was raising, to use Thomas’ words, “as a son,” which only underscores the significance of the favor Crow did for him.

There is a tendency, which is understandable, to view these disclosure stories through the lens of the corruption they lay bare. It is all very corrupt, if not in the legal sense—the Supreme Court essentially ended public corruption as a concept already and effectively polices itself—than as a matter of common sense. Thomas treated a basic requirement of his job with the good-faith and rigor of a Trump Organization accountant trying to justify a deduction.

“Neither Harlan Crow, nor his company, had any business before the Supreme Court,” Paoletta noted in his statement, echoing the line we’ve heard before, as if Crow is just a regular businessman with a passion for Viennese impressionists. It is almost too obvious to point out that the business of a political donor is the Court. Crow and Leonard Leo did not meet Thomas at Walmart; they are friends, you would say, from work.

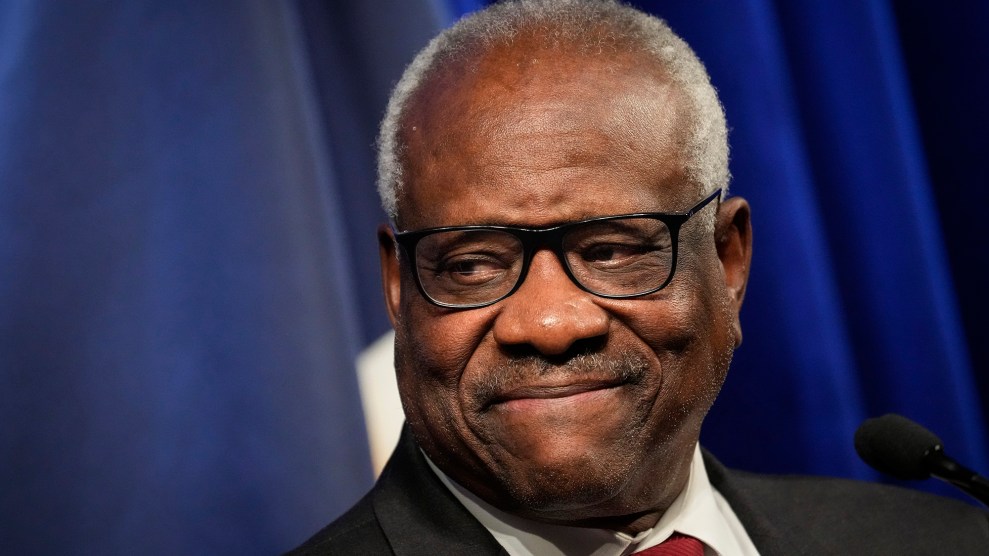

But this is not just a story about conflicts of interest and ethics and the importance of strong male friendships. The half-baked justifications, and the people who rally around them, are a kind of blueprint, too, for the way this whole world operates. The modern conservative legal movement is, in the simplest sense, about finding a way to the outcomes its proponents want. Over the last 40 years or so, that movement has often couched those outcomes in the lofty idea of “originalism,” arguing that Federalist Society jurists were applying a rigorous, almost-scientific rubric to settling legal questions in a judicious manner. It was useful, both as a branding exercise and as a vehicle—it turns out that you can get a lot of modernity thrown out just by setting as a baseline the writings of 15th-century exorcists.

But the outcomes were always the point, and the philosophy of interpretation was a pretext to reinterpret what they wanted: An entirely new Second Amendment; a very old and enfeebled administrative state. That was what brought all those activists, donors, and strategists together.

There is not really an originalist position on a mandatory federal financial disclosure form. But to watch Thomas and his friends defend his novel understanding of transparency—to listen to increasingly convoluted efforts to explain why a gift is not a gift (and by the way, thanks again)—is to see the conservative legal movement for the mercenary program that it is. Strip aside the airy invocations of the founders and they all just sound like an army of well-compensated, white-shoe lawyers arguing on behalf of a conglomerate that, actually, organ harvesting is a kind of agriculture.

This is the work: Find a loophole, or make one. Justify the conduct you want. You can find a founding father to say anything, but it’s regulatory capture all the way down.