This article was produced in partnership with the nonprofit newsroom Type Investigations, with support from the H.D. Lloyd Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Any woman who works in the maritime industry will remember where she was when she read about Midshipman X.

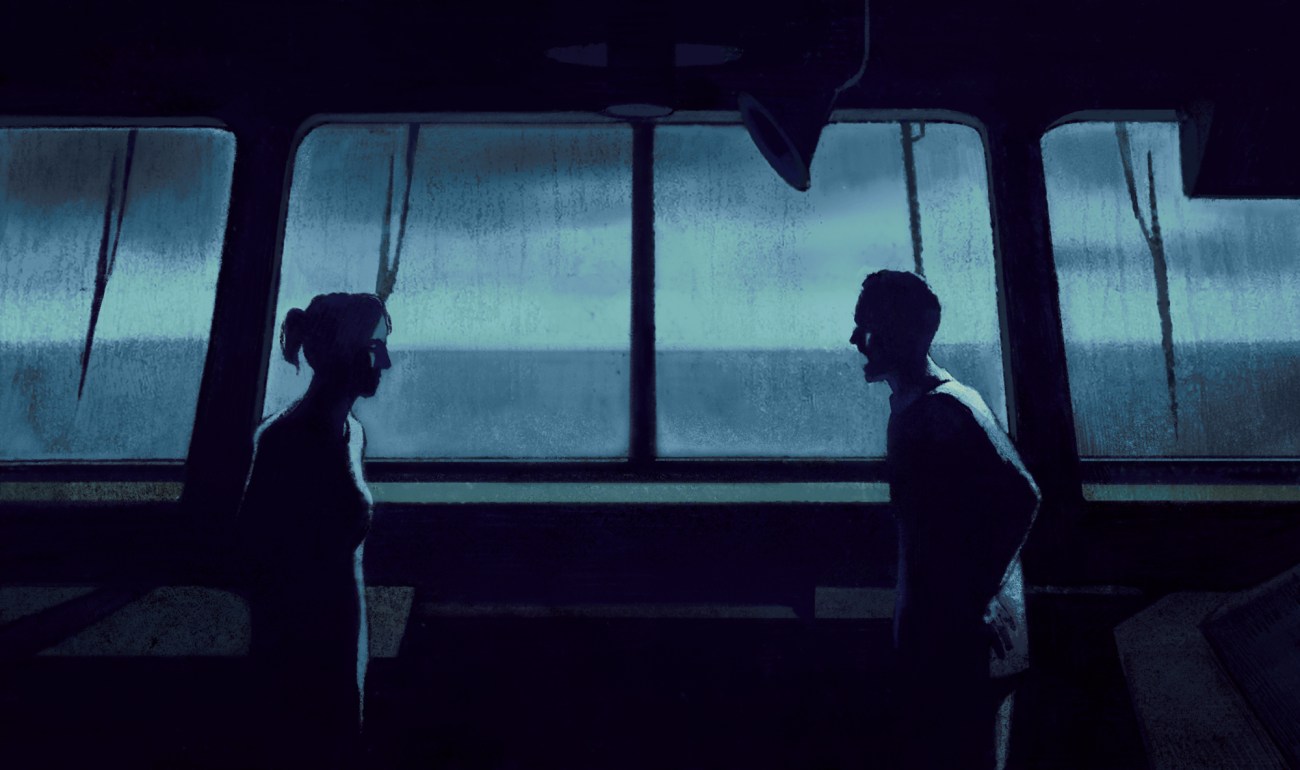

This was the pseudonym used by a student at the US Merchant Marine Academy when she published a blog post in September 2021 alleging that, as a 19-year-old cadet on board a cargo ship, she was raped by a senior officer. Afterward, the officer intimidated and threatened her; she had to remain on the ship and work alongside him for another 50 days.

The horrific specificity of Midshipman X’s account jolted the offshore world, as did the fact that she had written about it so publicly. In the Merchant Marine, the ubiquity of sexual violence against women is almost never acknowledged. But Midshipman X wrote that of the more than 50 women in her academy class, she had not spoken to a single one who “has not been sexually harassed, sexually assaulted, or degraded” during their time at the academy or while training offshore. She alleged that five cadets in her class were raped at sea.

The post went viral, and politicians and industry leaders were quick to express outrage. Midshipman X had not identified herself, but the details in her account allowed the Danish shipping behemoth Maersk Line, Limited, to extrapolate that she had been working on one of its ships. The company’s CEO said he was “shocked and deeply saddened.” The company then opened an investigation and suspended five crew members. The alleged perpetrator was fired, as were four other crew members: two for breaking the company’s policy against alcohol on board, and two for refusing to comply with the investigation of Midshipman X’s allegations. The Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration, which oversees the Merchant Marine Academy, announced that it would reassess safety procedures designed to protect cadets offshore. In a letter to the USMMA community, Deputy Transportation Secretary Polly Trottenberg and Acting Maritime Administrator Lucinda Lessley stated “unwavering support” for Midshipman X and reiterated a policy of zero tolerance for sexual misconduct.

For a lot of women, these statements felt empty. The way women are treated offshore has long been whispered about, and on rare occasions, stories of sexual violence at sea have broken into the news. In 2016, the Maritime Administration temporarily stopped placing USMMA students on board working ships over concerns about sexual assault. But for the most part, the industry has looked the other way. Ally Cedeno, a mariner turned advocate, read Midshipman X’s account and immediately thought of a long-ago experience of her own, and all the similar stories that women had told her over the years. “I can’t be surprised, knowing what I know about the industry,” she said. “How many more situations do we need to wake people up?”

Midshipman X’s post landed in the #MeToo era, and soon many other women began sharing their own stories of harassment and assault, and also pregnancy discrimination, bullying, racism, and, above all, relentless misogyny. They spoke in devastating terms about the psychological toll. “When I’m working, every emotion stops,” a mariner named Madeleine Wolczko told me. “I can pull it together for four months and be an extremely professional human. And then I probably cry every day when I’m off the ship.”

In June 2022, on the cusp of graduating from the academy, Midshipman X revealed that her name was Hope Hicks, and she filed a civil suit against Maersk. Her goal was not only to win her case, she said, but to draw attention to “the toxic culture of unpunished sexual harassment and sexual assault that plagues” the maritime world. Hicks has since repeatedly called out unions and the US Coast Guard for failing to hold abusive men accountable. “We all know there are people in this industry who have been reported for sexual harassment and sexual assault…but allowed to remain members of their labor unions and to simply join another ship,” she has written. “This lack of real legal accountability for sexual predators in the maritime industry, and the almost total absence of regulatory oversight on this issue, has perpetuated an endless cycle of harassment and abuse.”

Advocates argue that the ubiquity of sexual misconduct on ships forces women to leave the industry and keeps it overwhelmingly male, perpetuating the hostile environment for the women who remain. They are determined to use Hicks’ case, which has drawn unprecedented attention, to push for meaningful reforms. “The industry overall is behind in supporting women,” Cedeno said in October 2021 on a podcast devoted to sexual assault offshore. “Unless changes are brought forth…we will continue with the status quo of victims being silenced, of sexual assault and harassment happening in the industry without consequences, and women and other marginalized groups being pushed out.”

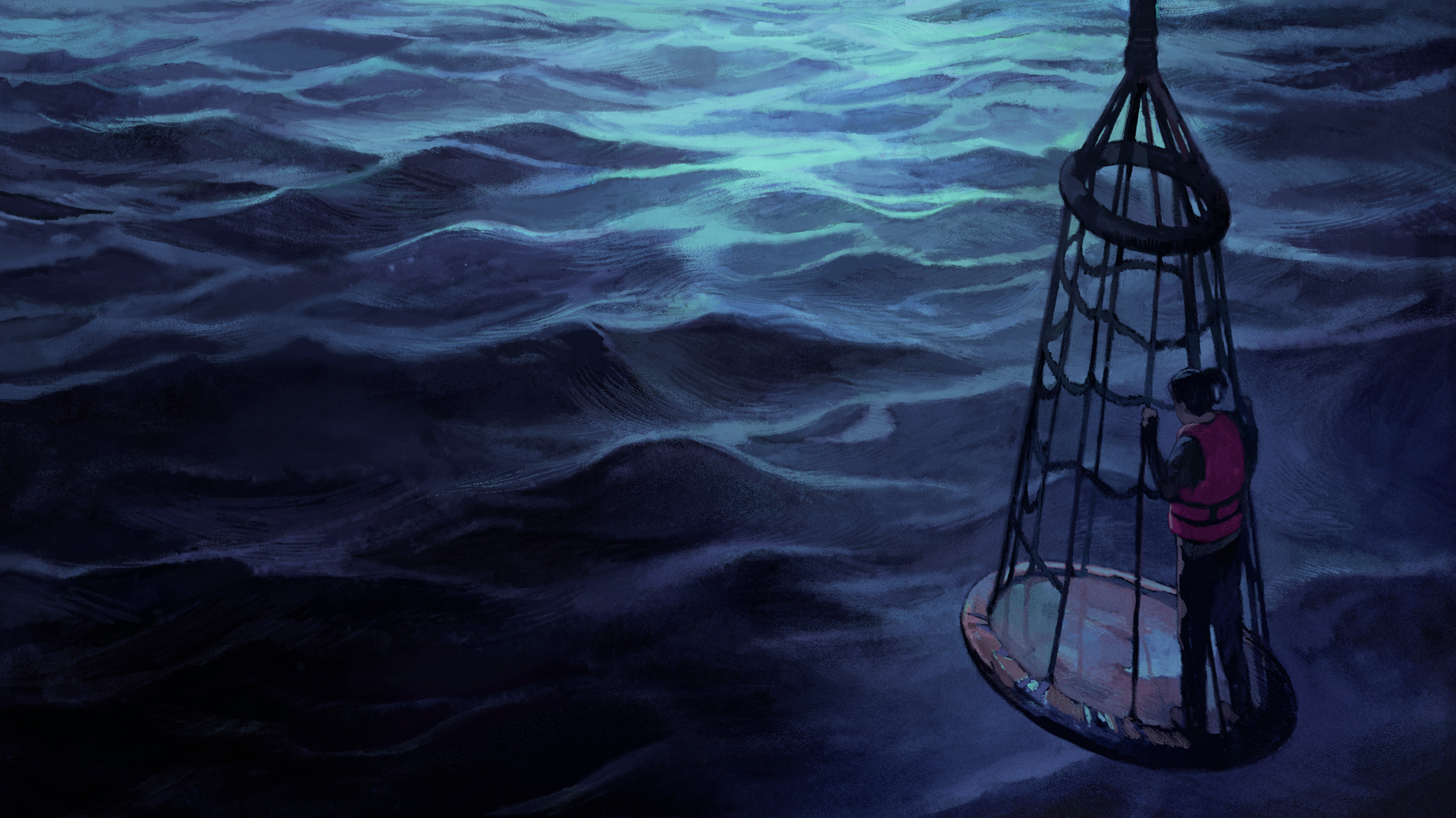

Life offshore sounds like a concept for a reality TV show: Put a group of strangers together in an isolated environment, deprive them of sleep, their families and friends, days off, and a means of escape, and then see who survives. But this is the way of life for 2 million seafarers across the world who staff the oil rigs, container ships, and car carriers that help keep the global economy moving. Offshore work is one of the most dangerous jobs in America—the fatality rate for maritime transportation workers is six times higher than that of the average US worker. Though mariners work largely out of sight, almost every object we buy has spent some amount of time on the ships they operate.

For centuries, superstitious seafarers believed that a woman’s presence aboard a working ship would lead the boat into troubled waters. Women were “the Devil’s Ballast,” sailors often said, and the tensions the expression suggests still remain. Maritime work is one of the last jobs that is truly a man’s world. Globally, over 98 percent of seafarers are men. (The active-duty US military, by comparison, is 83 percent male.) The roughly 24,000 women who work in the industry worldwide choose to live in an environment that often doesn’t want them to be there. The US Merchant Marine Academy didn’t begin accepting women until 1974; even then, they were hardly encouraged to apply.

In the mid-’80s, an advocacy group called the Women’s Maritime Association convinced Congress to launch an investigation into sexual violence at sea. But Government Accountability Office investigators reported that while they’d collected testimonies, they found it impossible to fully assess the situation, given that the isolated, dangerous shipboard environment required mariners to be “highly dependent” on one another. Women were dissuaded from “incurring the animosity of male crew members by reporting instances of sexual assault.”

In recent years, companies have begun actively recruiting women. But while the global number of female mariners almost doubled since 2015, “women are still encountering the exact same stuff that women of my generation had to deal with,” says Ann Sanborn, who became a mariner in the late ’70s before becoming a professor at the USMMA. “Sadly, I think I’m going to be ending my career with some of the same issues I started with.”

While reporting this story, I spoke with 20 women who experienced some form of sexual misconduct over the course of their careers offshore, ranging from verbal harassment to rape. “You’re in the middle of the ocean, thousands of miles away from everybody else,” says K. Denise Rucker Krepp, former chief counsel for the Maritime Administration. “You can’t just get in your car and drive to the emergency room and get a rape kit. Even in the military, you see different people on a regular basis. At sea, it’s the same people, and if you report, immediately everybody knows.”

Today, even on large vessels of a couple hundred workers, there might be only one or two women on board. Female mariners told me about men waiting in line for dinner who mimed slapping women’s asses, who pressured them to dance in the gym, who followed them to their rooms, who cornered and kissed them. “My first job offshore was on a supply boat in the Gulf of Mexico,” one mariner said. “I was the only girl who ever worked there—ever. The first night, some guy handed me a fishing filet knife and said, ‘I want you to sleep with this right next to your bed.’”

Ally Cedeno attended the USMMA in the early aughts. During her junior year, she was placed as a cadet on a tanker in the Gulf of Mexico. When she introduced herself to her supervisor, she says, he screamed, “‘Get out of my face! I specifically asked for you not to be here.’” She didn’t know if it was because she was a woman or a trainee, but she couldn’t shake the thought that a chief mate would never speak that way to a male cadet. The emotional abuse continued for months, Cedeno remembers. Asking to leave would have meant giving up on the certification she was working toward, so she pushed through. As she spent more time at sea and met other women mariners, she realized that “every woman offshore has had some sort of sexual harassment experience, and many have experienced assault or worse.”

In 2017, after a decade in the industry, Cedeno launched a nonprofit called Women Offshore to help women share experiences, commiserate, and strategize. She raised early funds from Transocean and Seadrill, two maritime companies that wanted to support her work and advertise their own efforts at inclusivity. Soon, women were contacting Cedeno for help with all sorts of problems. They told her about being stalked and raped, about hazing, about their employers telling them they couldn’t go to sea if they got pregnant.

These issues weren’t being widely addressed by companies, unions, or anyone else. Many women told Cedeno they didn’t even know where to turn to resolve their concerns. The Coast Guard oversees the US Merchant Marine, administering mariners’ credentials—which determine rank and the size of ship a mariner is qualified to crew—and regulating the private companies that employ them. It also has the authority to investigate crimes and less serious offenses and to revoke credentials if mariners are found guilty. But the process is complicated, especially since many American merchant mariners work on foreign-flagged ships.

If a crime involving a US-credentialed mariner is committed at sea, jurisdiction for an investigation depends on where the ship is located when the incident happens; it may be handled by the Coast Guard, local police, or the FBI, sometimes in collaboration with each other. If an incident takes place on a US ship in foreign waters, Coast Guard investigators might collaborate with foreign law enforcement. Following the December 1988 GAO report, Congress passed a law requiring that the captains of US-flagged ships report any incidents of sexual misconduct to the Coast Guard. But the Coast Guard did little to publicize or enforce the new rule. When Anne Mosness, then-president of the Women’s Maritime Association, asked why, a Coast Guard official told her that the agency didn’t consider rape a true safety threat.

Documents I obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request indicate that between 2003 and 2018, the Coast Guard received only one report of criminal sexual violence in the Merchant Marine. It declined to recommend prosecuting the case. In December 2021, the Coast Guard issued a bulletin reminding captains of the reporting requirement’s existence. (In a statement to Mother Jones and Type Investigations, a Coast Guard spokesperson acknowledged that before 2021, it received “very few reports” of sexual assault or harassment, in spite of the maritime industry’s “underlying culture permissive to violent behavior.”) After the bulletin went out, reports of sexual offenses “increased rapidly.” As of December 2022, the agency said it had 26 active investigations, compared with just one in 2019.

When it comes to harassment or bullying, Cedeno says, “the Coast Guard says it’s a culture issue and needs to be handled by the companies. But so much that is assault gets dismissed as harassment, and then harassment gets dismissed as nothing.” When she talked with male mariners about Hicks’ account, Cedeno adds, “there was pushback: ‘If it happened, why didn’t she report it?’” Cedeno tells them: “Well, you need to have trust in the system. That trust isn’t there.” Most women who contact her say they had little faith that reporting misconduct would be worth it. The maritime world is small, and rumors travel fast among workers cooped up together for months at a time. (“Anyone that thinks that teenage girls gossip—they ain’t got nothing on a bunch of middle-aged sailors,” one mariner told me.) Women fear that if they speak out they will have a hard time getting hired in the future.

“We live with our co-workers,” says Elizabeth Simenstad, who worked offshore for 13 years and founded Sea Sisters, a networking organization for female mariners. “If you report something and they ostracize you or further victimize you—that’s one of the biggest problems. We’re so close to the danger.”

When Cedeno launched Women Offshore, she believed that the way to remake the culture at sea was to show clearly that women belonged there, by building a critical mass of female mariners who were connected and supported one another. The more women on board a ship, the less likely it would be for men to target them for bullying or violence and for companies to ignore their needs. Soon Women Offshore’s leadership began providing DEI consulting to maritime companies in exchange for funding for its mentorship program, career development events, and the yearly conferences that host up to 300 mariners.

Cedeno found that while some companies simply wanted to put out a press release saying they had worked with Women Offshore, others were actually invested in changing the way they operated. In 2018, Transocean, whose offshore workforce was 1.3 percent women, announced a goal of increasing that number to 25 percent. “Everybody in the industry literally laughed at them,” Cedeno says. “But I loved that. If you don’t set ambitious goals, you’re never going to get anywhere.”

In 2019, the Department of Transportation asked Cedeno to join the USMMA Advisory Board, and she used the opportunity to develop a strategy for changing the Merchant Marine culture. After Hicks came forward, much of Cedeno’s plan was written into a bill called the Safer Seas Act, introduced in early 2022. It ordered the Coast Guard to revoke the credentials of any mariner convicted of sexual assault in the past 10 years; someone found guilty of harassment could have their credential revoked or suspended.

Cedeno was especially excited about a provision that required anybody who witnesses sexual misconduct on board a Coast Guard–documented vessel to report it or be subject to a fine; she hoped it would make mariners more acutely aware of the scope of the problem. “It’s not going to fix everything overnight,” Cedeno says, “but it will make people aware that they’re going to face consequences for not reporting or for allowing sex offenders to work in their companies.” The bill also required all commercial ships to install cameras outside sleeping quarters, in an effort to discourage the widespread problem of men stalking female mariners and trying to enter their rooms. Shipping companies and lobbyists for industry groups and unions pushed back on several of the bill’s provisions, especially the proposed surveillance.

Then the bill was folded into the annual Coast Guard Authorization Act. In spite of the service’s assertions that it wants to take sexual misconduct offshore seriously, “we experienced tremendous opposition from the Coast Guard to expand this to sexual harassment,” says a Democratic congressional aide familiar with the negotiations. Republicans on the Senate Judiciary Committee killed the bystander provision. But the camera requirements made it into the final version over industry objections, and it passed last December.

A month earlier, Hope Hicks had settled her lawsuit against Maersk. She is barred from disclosing the terms of the agreement, but the company publicly promised new training, reporting, and accountability measures to ensure its ships are safe. “The changes that MLL has proposed are an important first step, but there is still a lot of work to be done in the maritime industry,” Hicks said in a statement. The Coast Guard didn’t take responsibility for keeping the alleged perpetrator off other vessels and even renewed his credentials in 2022. And Hicks later revealed that though Maersk had fired the man she accused of rape, another shipping company later hired him.

No matter what legislation is passed or how many settlements are awarded, the industry’s cultural issues don’t have quick fixes. They are upheld by men who have sat atop the maritime world’s hierarchy for years. Cedeno says that female mariners who have been assaulted offshore often try to find ways to move through the trauma, because of their desire to keep working. Many later leave the industry. “There’s this type of torture, punishment by little cuts,” Cedeno says. “After a while, you wonder, do I even have a career? Do I want to be here? You question that a lot. It seems like it will just never end.”