On a hot afternoon in June, some 700 seated attendees of the annual summit of the conservative parents’ rights group Moms for Liberty bowed their heads in prayer. The Moms had waited in a security line that spanned two floors of the Philadelphia Marriott to get here, and even during this somber moment, the giddiness in the ballroom was palpable as they geared up for the highlight of the conference: a speech by former President Donald Trump.

Up at the dais, wearing a shiny green satin T-shirt that stood out against a row of American flags, Moms for Liberty advisory board member and wife of Rep. Byron Donalds (R-Fla.) Erika Donalds offered an invocation. “Lord, you have elevated this organization to do your good work in this country,” she said. “We’re grateful that the truth is being exposed, that parents are being able to see what’s really going on in education in our country.”

Presumably, Donalds was referring to the litany of complaints about public schools that had emerged in the conference breakout sessions: how they were corrupting children with lessons about institutional racism, gender diversity, and sex ed. Trump, when he finally took the stage, put a finer point on these forces of corruption, decrying the “radical left, the Marxists and communists” who had supposedly taken over American education. Then, he thanked Donalds by referring to her as “Byron’s wonderful wife.” He went on, “Where is she? I hope she’s here somewhere because she is an incredible person!”

Trump’s hour-and-a-half speech was a meandering affair, but the Moms were rapt: They booed when he accused President Joe Biden of arranging his indictment, and whooped when he complained about “the 87 different genders that the left says are out there.” But possibly the loudest applause of all came when he returned to the topic of education. “By the way I want to move our education system back to the states,” he said. The audience exploded. “You hear that, Erika?”

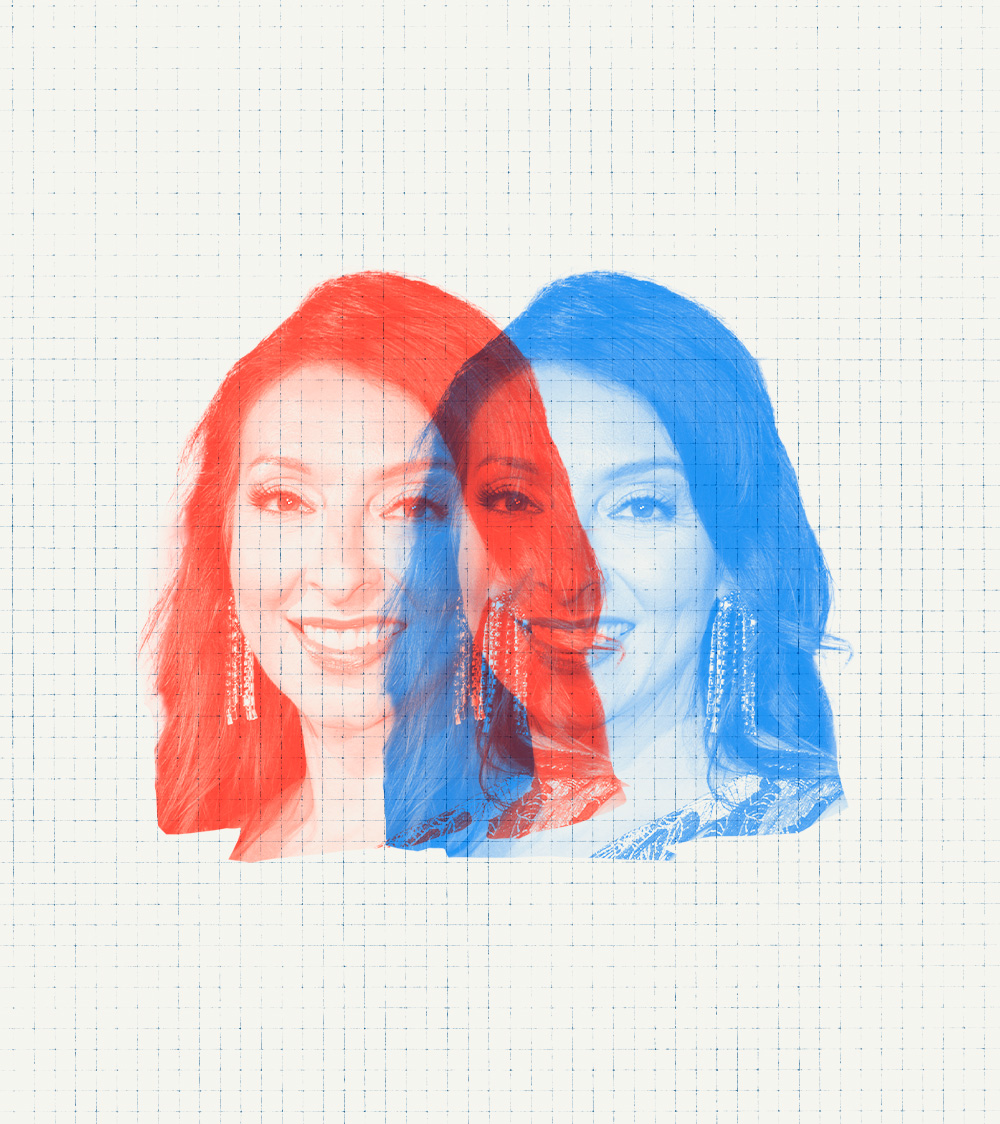

That Donalds received two separate Trump shout-outs was noteworthy because, well, she’s not all that famous, at least not outside of her home state. A former school board member from Collier County, Florida, she now runs a local network of charter schools—you’re more likely to have heard of her congressman husband, a Black archconservative who has been touted as a potential Trump running mate in 2024. Trump’s praise of Donalds was even more striking given that she was, until recently, a golden child of one of Trump’s Republican opponents. Over the last decade, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis helped position Erika Donalds as an educational power player in the state, elevating her work and appointing her to key committees. In return, Donalds has had an outsize influence on Florida’s educational policy, says Sue Legg, a retired University of Florida professor of education who has followed Florida’s move toward conservatism in education.

But in recent months, as DeSantis’ political fortunes shifted, Donalds appears to have dropped the governor and instead hitched her star to Trump’s wagon. Legg believes it’s possible that Donalds may be on the list of possible Trump picks for the next secretary of education, the role previously filled by charter-school crusader Betsy DeVos. In addition to her school-choice advocacy, DeVos threatened desegregation efforts, rolled back Obama-era protection for transgender students, and has openly called for the dismantling of the Department of Education. “Betsy DeVos was a disaster,” says Legg. “I think Erika Donalds could be worse.”

A fourth-generation Floridian born in 1980, Donalds grew up middle class in Tampa. Her current passion for education wasn’t on display in her early life; in a 2015 interview with the News-Press, she recalled being a mediocre high school student, buckling down only after she learned she would be thrown off the basketball team if she couldn’t get her grades up. With the help of her churchgoing grandparents, she raised her GPA and narrowly qualified for admission to Florida State University, where she excelled, graduating magna cum laude in 2002 with a degree in accounting. It was at Florida State that she met her husband, Byron, who became a Christian after attending Erika’s evangelical church. The pair got married shortly after graduation and moved to the affluent town of Naples in Southwest Florida’s Collier County. Erika went on to earn a master’s degree in accounting from Florida Atlantic University, then to work her way up in an investment firm, an experience that would later serve her well when she became a charter-school entrepreneur.

In 2013, when the second of Erika and Byron’s three sons was in elementary school, the couple began to question the public school that their children attended. During his speech at this year’s Moms for Liberty summit, Byron Donalds recalled his son struggling with math homework that followed the instructional method endorsed by the federal Common Core education program under Obama, which many conservatives see as an example of federal government overreach. “I remember it like it was yesterday,” said Byron. “He’s sitting at the kitchen table. He’s got tears in his eyes crying. ‘This is how they’re teaching me.’ And I said, ‘Son, I don’t know what they’re teaching you. But I promise you this. In the real world, you get fired over doing math like that.'” The Donaldses promptly pulled their son out of their neighborhood public school and enrolled him in private school.

That experience seems to have made a strong impression on Erika Donalds; she soon began advocating for school choice, an educational policy movement that champions charter schools and private school tuition vouchers as alternatives to public schools. In 2013, she helped found a group called Parents’ Rights of Choice for Kids (Parents ROCK), whose members, foreshadowing the current parents’ rights movement, railed against what they saw as government intrusion into the sacred relationship between parents and children. In a July 2013 Facebook post, the group wrote, “We are fighting so hard for all of these parents, and many more who are still unaware that their parental rights have been snatched away by an overreaching school district, hungry for more money and control.”

The next year, Donalds won a seat on the five-person school Collier County School Board. The job, she found, wasn’t easy: Donalds argued valiantly against what she saw as progressive causes—for example, she opposed a school dinner program to feed an evening meal to hungry students, telling the Naples Daily News, “I think these students need to be home with their families, having dinner with them, not being bribed to stay after school and us becoming basically their second home.” She took every chance she could to oppose Common Core. But no matter how hard she tried, Donalds and the other conservative board member, Kelly Lichter, found themselves losing every vote to the three-person liberal majority.

Donalds became adept at racking up small victories even among her political adversaries. In 2017, she managed to convince her fellow board members to reduce the amount of school-related taxes that residents were required to pay. “I was very impressed with Erika—she was very politically astute,” said Kathy Ryan, a retired Collier County educator who ran against Donalds for school board in 2014. “Erika would remain calm and occasionally get something done. She got some compromises through by not getting into a big argument, but by laying back at the right moment and knowing when to suggest a compromise.”

She was also good at finding allies. The Florida School Boards Association at the time leaned left, so Donalds helped to launch a splinter group for conservatives who advocated for school choice, which she called the Florida Coalition of School Board Members. Other early members of the group were school board members from Sarasota and Brevard County, Bridget Ziegler and Tina Descovich, who would later go on to help found Moms for Liberty.

While on the Collier County School Board, Donalds formed a friendship with her fellow embattled conservative. In 2014, Lichter had launched a new school in Naples called Mason Classical Academy. The Donaldses enrolled their children, and Lichter appointed both Erika and Byron as members of the board. Lichter founded Mason in partnership with the Barney Charter School Initiative, a network of schools run by the ultraconservative Christian Hillsdale College in Michigan. Hillsdale accepts no public funding but instead relies on generous donations of wealthy conservatives, including from the family of Betsy DeVos. In recent years, the college emerged as a power player in conservative policy; Hillsdale president Larry Arnn led Trump’s 1776 Commission, a group that challenged the idea that the damaging legacy of slavery has shaped American history.

Hillsdale College has over the last 10 years helped found dozens of classical academies serving more than 15,000 students across the United States, with more opening every year. In its charter schools, including at the time of its founding Mason Classical Academy, Hillsdale employs what it describes as “traditional” teaching methods. Elementary schoolers practice cursive, learn parts of the Constitution by heart, and recite their multiplication tables. In middle and high school, students focus on the Western canon; few books from other cultures are included in the curriculum. For history, the schools use the 1776 Curriculum, which Hillsdale developed as a conservative answer to the New York Times’ 1619 Project on the legacy of slavery in the United States. Through these pursuits, Hillsdale says, the students receive an education “that is rooted in the liberal arts and sciences, offers a firm grounding in civic virtue, and cultivates moral character.” By serving on the board at Mason Classical Academy, Donalds developed relationships with key players in Hillsdale’s charter school network.

Preston Green, a University of Connecticut education professor who has studied the school choice movement, believes that Hillsdale may be laying the groundwork to deliver Christian education through publicly funded schools. He pointed to the example of a Catholic school in Oklahoma, which if it opens as planned in 2024 will become the nation’s first religiously affiliated charter school. Green says he expects the Supreme Court to take on the issue of religious charter schools in the near future. “Hillsdale has the infrastructure and the mechanism for delivering religious charters if and when the Supreme Court gives the go-ahead.”

Rep. Byron Donalds (R-Fla.) speaks during the Moms for Liberty Joyful Warriors national summit at the Philadelphia Marriott Downtown on June 30, 2023.

Michael M. Santiago/Getty

While Donalds was learning the ropes of conservative education activism through the school board and Mason Classical, her husband, Byron, was busy building his political career. Like his wife, Byron worked in finance, but in 2010 he had begun to dabble in right-wing politics, speaking at tea party rallies. To say that Byron must have stood out in that lily-white crowd would be an understatement, and the opportunity to groom a Black conservative was not lost on local Republicans. They urged him to become more involved in politics and then run for office. In 2016, Byron was elected to the Florida House of Representatives, where his signature issue was school choice. In 2017, he sponsored legislation that dramatically expanded state funding for charter schools. Under the proposed law, the state would pay millions of dollars in management fees to charter school companies that served in areas with low-performing public schools.

But in 2018, cracks began to appear in the leadership of the charter school that was closest to the Donaldses’ heart, Mason Classical Academy. Donalds and her fellow conservative school board member, Kelly Lichter, got into an argument that morphed into an all-out legal battle. To hear Donalds and her allies tell it, the board that Lichter had appointed had engaged in questionable financial practices, leaving the school’s budget in ruins. Lichter, however, maintained that Donalds was conspiring with Hillsdale College to wrest control of the school from Lichter. Donalds pulled her children out of Mason Classical Academy and resigned from the board. Hillsdale College, too, parted ways with Mason Classical, but Donalds kept close ties with the Hillsdale leaders she had met through the school. (The dispute over the school was supposed to end in mediation, but several related lawsuits are ongoing.)

Donalds opted not to run for reelection for the school board in 2018, but her career as a conservative operative in Florida education politics was just getting started. That year, newly elected Gov. DeSantis began to take notice of Donalds, appointing her to his educational transition committee. Then, his commissioner of education, Richard Corcoran, appointed her to Florida’s Constitution Revision Commission. In that group, with the help of several other members of her conservative school board group, she launched a campaign for an amendment that bundled two relatively uncontroversial moves—imposing term limits on school board members and making civics education a requirement in Florida schools—with an edgier one: limiting the authority that boards had over charter schools. That part of the amendment was ultimately removed from the ballot, but the other two items passed.

But Donalds had achieved something more significant: an in with the upper echelons of Florida government. “We need to show strong support for our bold and courageous Governor who is doing what he said he would do for Florida’s children,” she gushed in a Facebook post in 2019. “Such exciting times!” That same year, she told the Tampa Bay Times, “My time on the School Board really led me to conclude that the best prescription for school reform is the free market.”

True to her word, over the next few years, Donalds began to build an empire around Hillsdale’s charter schools. In 2017 she had quietly launched OptimaEd, a for-profit company with the explicit intention of expanding Hillsdale’s network of schools. According to an early version of the company’s LinkedIn page, “Optima’s goal is the successful launch of Hillsdale College Barney Charter School Initiative classical academies and other schools of excellence across the state of Florida.” In addition to OptimaEd, Donalds also launched another charter school management company called Classical Schools Network Inc., and a nonprofit, the Optima Foundation, both of which fundraise for the Hillsdale classical academies that Donalds’ company manages.

In the time since Donalds began advocating for school choice, charter schools have proliferated in Florida: In 2022, nearly 362,000 of the state’s students were enrolled in charter schools, up from just more than 200,000 in 2013. According to a 2023 report by the education advocacy group Network for Public Education, about half of Florida’s charter schools are run by for-profit companies, compared with 17 percent nationwide.

Donalds’ companies are among those cashing in on the Florida charter school boom. In 2021, with the help of the Hillsdale team, she launched Naples Classical Academy, a 70,000-foot campus just 15 miles away from Mason Classical Academy. In addition to Naples Classical, Optima manages four other classical schools. Through these contracts, OptimaEd brings in a tidy profit each year: The company charges a fee of between 10 and 12 percent for its services. At Naples Classical Academy, for example, in the 2021–2022 school year, the last year for which a financial audit is available, the school brought in a gross revenue of nearly $10.5 million—netting a fee of about $1.2 million for Optima. At the same time, Donalds’ Optima Foundation is raking in donations for the schools that her company manages.

And what are schools getting in return for those fees? This year, Treasure Coast Classical Academy, an OptimaEd-managed school in Martin County, Florida, commissioned an independent evaluation of OptimaEd’s management of the school. The resulting report raised concerns about blurred lines between Optima and the school: It found that OptimaEd had hired key staff away from the school, asked school employees to do extra work for OptimaEd without compensation, and that Donalds had given herself ultimate authority over the school’s board, an arrangement that the auditor found odd. “In my experience, a charter school executive director does not ordinarily have the authority to ‘allow’ his or her board chair to do anything,” he wrote. In general, the evaluation found that the faculty seemed to resent OptimaEd’s authoritarian style of management. One school staffer noted that when she and her colleagues raised concerns, OptimaEd typically responded with “a faculty meeting where they basically gaslit the faculty and told us if we cared about the kids we wouldn’t have these opinions. It made us all afraid to be honest in fear of backlash which we had no power to speak for ourselves.”

The audit seemed to reveal low morale that was caused at least in part by the faculty’s perception that OptimaEd prioritized profits over investment in the culture of the school community. As one faculty member told the independent auditor, OptimaEd seemed “to be driven more by their own financial gain than that of the teachers that are responsible for making sure all scholars get a prime education.” Another noted that OptimaEd “seems dedicated to profit sometimes to the detriment of the school itself.”

In an email to Mother Jones, Donalds called the audit “not independent, but instead part of a coordinated effort to essentially unionize the charter school’s teachers.” But there is evidence that Treasure Coast Classical Academy wasn’t the only school dissatisfied with OptimaEd’s management services. The two classical academies in Jacksonville recently ended their management agreement with the company. In the background of all this was legal trouble for Donalds: In 2022, Lichter filed a federal lawsuit against Donalds and Hillsdale president Larry Arnn over their dispute about Mason Classical Academy, making accusations of conspiracy, libel, and racketeering, among other charges. (Donalds told Mother Jones that OptimaEd continues to support the Jacksonville classical academies “on an as-needed basis” and characterized the federal lawsuit as “without merit.”)

Throughout all this controversy, in 2022, Donalds continued to maintain a mutually beneficial relationship with DeSantis. In March that year, he appointed her a member of the board of trustees of Florida Gulf Coast University. As he campaigned for his second term as governor, Donalds was there to support him. In November of that year, the Donaldses hosted a fundraising event featuring DeSantis’ wife, Casey, at a Naples restaurant. “Be there to STAND WITH DESANTIS,” Donalds urged her Facebook followers.

So it was somewhat surprising when the very next month, Donalds’ Classical Education Network company threw a fundraising Christmas gala with special guests Donald and Melania Trump. Tickets ran between $10,000 and $30,000, with proceeds to benefit Donalds’ nonprofit Optima Foundation. Guests were offered the opportunity to take a photo with the former president and his wife. Since then, Donalds has tweeted about her support for Trump on multiple occasions. In April, when news of Trump’s indictment broke, she tweeted, “Praying for the Trump family today!” A few days later, she tweeted, “The Donalds are all in for The Donald in 2024!”

The distance between Donalds and the DeSantis campaign seemed to grow. In May, she groused on Twitter about Team DeSantis’ frequent fundraising texts, sharing a screenshot from her phone. “Seven DeSantis fundraising texts in the past 24 hours,” she wrote. “It’s going to be a long year folks.” In July, after DeSantis faced backlash for a revision in Florida’s history curriculum that would teach middle schoolers that Black people acquired valuable skills through slavery, Byron Donalds tweeted that “the attempt to feature the personal benefits of slavery is wrong & needs to be adjusted.” The DeSantis campaign’s rapid response director, Christina Pushaw, clapped back, “Did Kamala Harris write this tweet?”

Today, Erika Donalds is a busy woman: In addition to her charter school management work and her position as a Florida Gulf Coast University trustee, she sits on the board of Moms for Liberty and the advisory council of the conservative nonprofit Independent Women’s Forum’s Education Freedom Center, which says its mission is to advocate for “reforms to unleash a more vibrant education marketplace.” She also serves on the board of the company behind the Classic Learning Test, an explicitly Christian high school exam that the Florida legislature was reportedly considering as an alternative to the SAT. Donalds’ entrée into the parents’ rights movement has proven to be a savvy business move: The disgruntled conservative parents whom she encounters in these spaces are eager to hear about alternatives to the schools that they believe are corrupting their children.

In March, Donalds’ nonprofit, Optima Foundation, hosted a fundraising gala; sponsors included two libertarian groups—the lobbying organization Americans for Prosperity and the Florida-based think tank James Madison Institute—as well as Betsy DeVos’ school choice lobbying group the American Federation for Children. Exactly how much money the event brought in is unclear, but the funds likely came in handy for Donalds’ latest venture: Optima Academy Online, a remote-only classical charter school that issues each student a virtual reality headset—a strange project, considering that most technology is explicitly prohibited at Optima’s brick-and-mortar schools. Naples Classical Academy assures parents on its website, “We do not entrust the preparation of our next generation of Americans to an adult monitoring the students allegedly ‘learning’ from a computer program.”

Because of the nature of the programming, the virtual reality school is open to any student in Florida—though since its charter is through Collier County Schools, it is required to enroll half of its students from that district. In June, the Florida Department of Education noted in a letter to Optima Academy Online that the school had significantly overenrolled nonlocal students and penalized the district upward of $470,000. (Donalds told Mother Jones that OptimaEd responded to the letter arguing that the enrollment cap should not apply to Optima Academy Online under current law.)

But Donalds has bigger plans: This summer, she announced that the school would operate through a charter in Arizona. OptimaEd now sells virtual reality field trip packages to schools across the country—and private schools in Florida, Arizona, Idaho, and New Hampshire can use state voucher money to buy them.

As Donalds looks to expand her sphere of influence outside of Florida, it’s not hard to see why she’s turned away from DeSantis; at this point, it seems unlikely that he’ll be in a position to give her a national platform. As of early August, Trump appeared to have left him in the dust; the Florida governor was polling at just 16 percent to Trump’s 52 percent among Republican candidates.

If Trump were to tap Donalds as his secretary of education, University of Connecticut’s Green worries about her “removing even any ‘nudge nudge, wink wink’ toward the idea that [charter schools] are public.” He speculated that if Donalds were given such a position of power, she could lay the groundwork for allowing states to use public funding for religious schools—a move that could be especially advantageous for Christian Hillsdale College and its network of classical charter schools, as well as the companies helping spread their gospel.

Back at Moms for Liberty, Donalds closed her invocation by asking God to allow the attendees to “fulfill the call that you have for them.” She warned the Moms that this task, assigned by God, would require courage, patience, and endurance. Then, she assured God that she knew he believed in their mission. “We know that that will result in a better country,” she said. “America, the beautiful, the country that you established for your glory for our children and our children’s children.”