A canvasser with the Stop Cop City Vote Coalition speaks with an Atlanta resident. Brynn Anderson/AP

On Monday, more than 25 of the leading voting rights groups in Georgia—including Fair Fight Action and New Georgia Project, both founded by former Georgia state legislator Stacey Abrams—signed an open letter that strongly criticized what they described as voter suppression tactics happening in their state. The letter wasn’t addressed to Republicans. It was sent to Atlanta’s Democratic Mayor Andre Dickens, and the majority-Democrat Atlanta City Council, after an announcement that the city would use “signature matching” to verify the petitions for a city ballot initiative referendum on whether or not to build the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center, better known as “Cop City.”

“Democracy calls on us to defend the right to participate in our civic process, not only when it is politically expedient or easy, but in every instance––without fail,” they write.

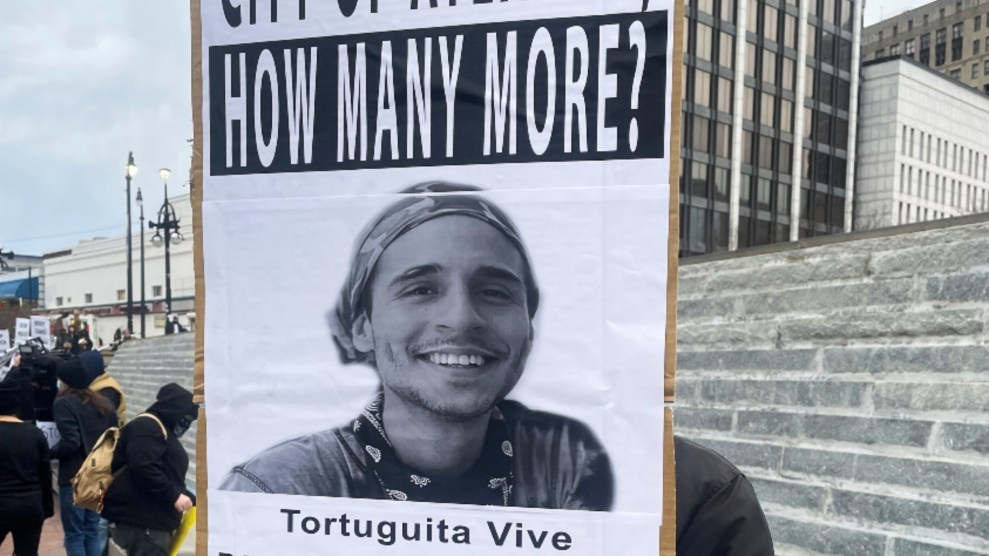

Cop City has become one of the defining issues in Atlanta politics over the last two years. Opponents of the project argue that Cop City will further militarize the police and raze vital green space, while supporters say that the new training facility is essential for police morale and retention.

Since June, the Stop Cop City Vote Coalition has led a campaign to gather enough signatures—between 70,000 and 80,000—to allow Atlantans to vote on whether to build the facility. Initially, they had 60 days to gather. In July a judge extended the deadline through mid-September. The city has already cleared most of the logistical hurdles to begin building Cop City—including an 11-4 vote from the Atlanta City Council in June to partly fund the project with public money (the rest of the funding will come from the Atlanta Police Foundation). But the Cop City referendum—modeled on a successful effort in Camden County, Georgia—is one of the final barriers.

According to a press release from the Stop Cop City Vote Coalition, they were prepared to turn in their 104,000 signatures on Monday––notably more than twice the amount of votes Mayor Andre Dickens received when he won in 2021—but over the weekend they heard from sources that the City might adjust the legal minimum signature count for ballot access, and that officials were planning to utilize a burdensome verification process. After the rumor spread, on Monday the coalition announced they were holding off until their September 23 deadline. That afternoon city officials sent a memo that announced the process to verify the petitions. It included “signature matching,” an ostensible fraud prevention method in which a prospective voter’s signature on the petition is confirmed to correspond with a signature from the same voter registered in the state’s database.

“In an effort to ensure that adequate resources are dedicated to this project, the City of Atlanta—through the adoption of the Atlanta City Council—has developed a step-by-step process to conduct the audit of the documents, of which the signature verification process maybe a critical element,” said Interim Municipal Clerk Vanessa Waldon in the city’s announcement.

This requirement is what has drawn the ire of voting rights groups in the state. “Signature verification is notoriously subjective, disproportionately impacts voters of color, and is biased against disabled and elderly voters,” Fair Fight Action wrote on Twitter. “Fair Fight calls on the @CityofAtlanta to rescind their intent [to] use this process, and to enact steps that fairly evaluate these petitions.”

Over thirty states use signature matching, but the practice has come under fire by voting rights groups and has been the subject of lawsuits that allege that it does more to weaken the democratic process than strengthen it. The ACLU has filed lawsuits against signature match laws all across the country because “a perceived signature mismatch heavily affects voters already at the margins—people with disabilities, trans and gender-nonconforming people, women, people for whom English is a second language, and military personnel.” In support of a lawsuit challenging Ohio’s signature matching law in 2020, a political scientist found that for every invalid ballot, thirty-two valid ones are thrown out. When the Stanford-MIT Healthy Elections Project analyzed the 2020 Florida primaries, they found that Black and Latino voters were twice as likely to have their ballots rejected.

For Democrats in Atlanta’s city government, it’s difficult for this use of signature matching to not look contradictory. In a speech focused on Republicans’ threats to democracy in January 2022 in Atlanta, President Biden called the city “the cradle of civil rights” while insisting on the need to pass voting rights legislation like the John Lewis Voting Rights Act and the Freedom To Vote Act. At the time, Mayor Dickens issued a statement saying that “I will personally do everything in my power to support the passing of those two very critical bills.” According to the Brennan Center for Justice, the “Freedom To Vote Act includes “safeguards to ensure fair resolution of discrepancies between a voter’s signature on a mail ballot and their signature on file with election authorities.”

Signature-matching has also become a major issue in Georgia politics. In 2018, Gwinnett County was the subject of two separate lawsuits over ballot rejections. When the data was analyzed, experts found that four percent of ballots from white voters were rejected, compared with 11 percent from Black voters, and 15 percent from Asian-American voters. Ahead of the Georgia Senate runoff in 2021, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected a lawsuit brought by the campaigns of Republican candidates Kelly Loefler and David Perdue that would’ve rejected more absentee ballots by changing the signature matching rules.

New Georgia Project Action Fund CEO Kendra Cotton issued a blistering statement on Monday, calling on Mayor Dickens and the city government to “immediately rescind this process and replace it with one built on sound, fair, and transparent procedures.” Cotton said the “arcane method to verify petition signatures in the push to get a referendum on Cop City on the ballot is the same method used for years by the GOP to throw out valid ballots cast by Georgia voters.”

So far, Atlanta has not responded to requests for clarity on multiple procedures from Cop City activists.

“The City should immediately announce a rolling cure process, where voters can find out if their signature has been rejected or counted as soon as that decision is made, and how to fix, or ‘cure’ their signature so they ensure it is in fact counted,” said Kate Shapiro, tactical lead for the Cop City Vote Coalition, in a statement. The city’s memo did not include details for how rejected signatures could be addressed.