When shelter-in-place orders swept the country in March, Ashima Yadava’s first thought was not just to rush home safely to California from New York, but to find ways to make more visible—and help alleviate—a threat indoors. Domestic violence had been her photography’s focus for eight years. She knew right away that isolation in unsafe homes amplified risks for millions of survivors, including people she advocates for. She’d been documenting survivors’ stories in portraits, and she saw immediately that “not all shelters are equal and safe to shelter in,” she tells me.

But she vowed to continue advocating. “The project closest to my heart is If Hands Could Speak, about domestic violence in the South Asian community in the Bay Area. I had to find a visual grammar to tell their stories without compelling them to relive their trauma. So I started to photograph their hands.”

If Hands Could Speak is a vivid, powerful portfolio of images, each answering the title’s question. Gesture, touch, texture, expression, and so many aspects of hands tell a story of how trauma goes unseen—and how, in creative forms, it is seen. In one image, two hands hold a third supportively; in another, fingers are bent back. As Yadava tells me, “Not all bruises are visible. Perpetrators often resort to hurting without leaving physical evidence of bruising, and twisting fingers is manipulative, intimidating, and deliberate because, in many ways, it signifies the possibility of more violence.”

In another image, hands drape across a chest in self-embrace or guardedness, or both. Each person decides for themselves if and how to participate, pose, reimagine, and share their stories, with Yadava’s support:

A drawing adorns the hand of one of the people photographed in Ashima Yadava’s If Hands Could Speak series.

The power of Yadava’s approach is not in documenting harm. It’s in reframing what survival and support look like; in finding a language to share and respect bodies’ experiences while protecting identities. She began If Hands Could Speak as an artist-advocate with Maitri, a nonprofit that launched in 1991 when a group of women created a confidential helpline for South Asian survivors of violence in the Bay Area.

Yadava speaks about herself and her work reflectively, choosing her words as deliberately as she chooses her themes and subjects—but “subjects” is not a word she uses. “I’m very conscious about the language of photography because we’ve known for a long time that photography is a power tool. How it oppresses. ‘Shooting people,’ ‘my subjects.’ They’re not. They’re not my subjects—they’re people.”

She calls up Sustan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others as a foundational work to illustrate a photographer’s role, and Teju Cole’s essay about the camera as a weapon of imperialism. She also mentions Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind as a reminder of how civilizations progress by collaborating. “Stories are never one-sided,” she says. “I need to keep sharing my power with the people I photograph.”

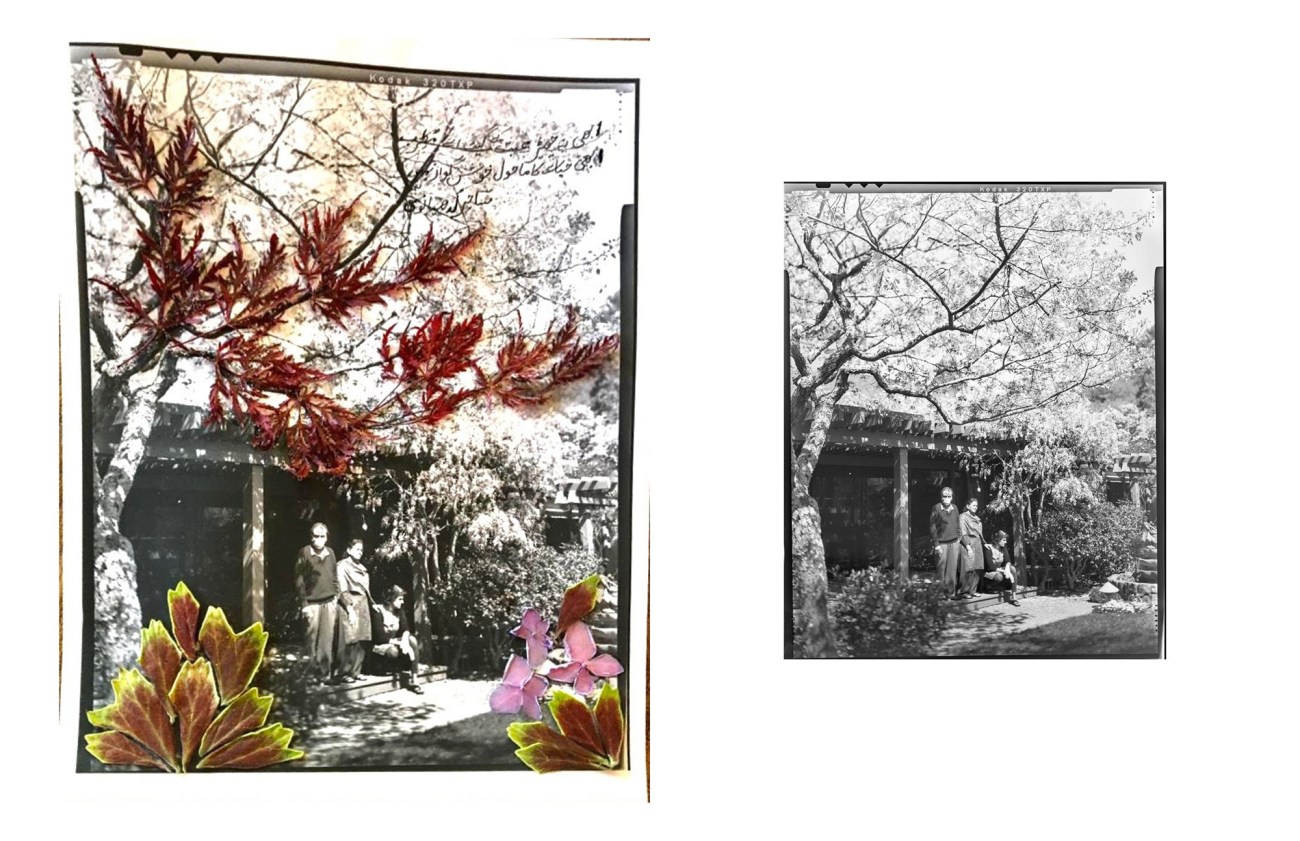

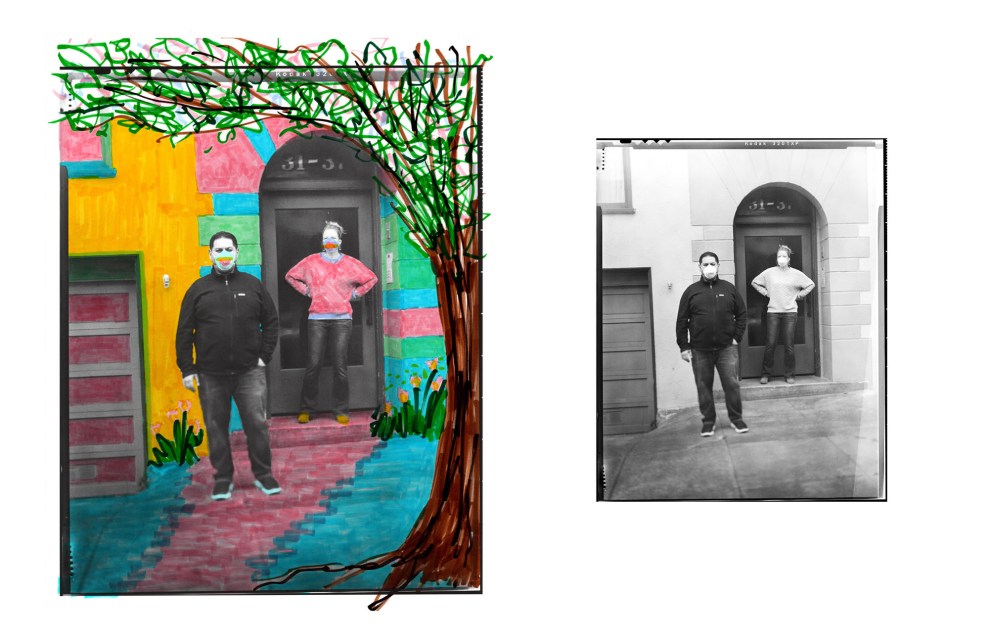

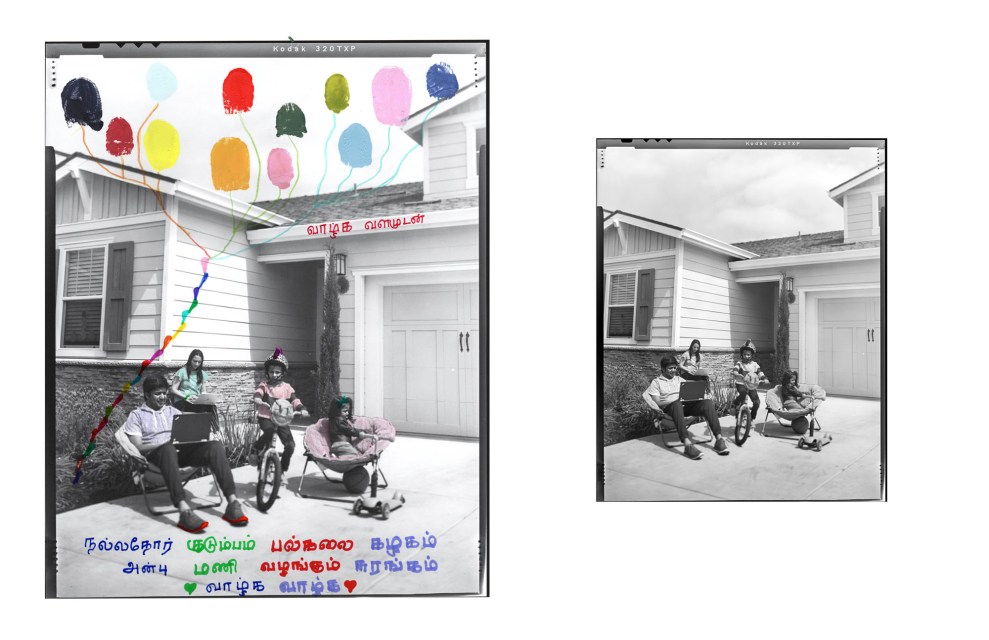

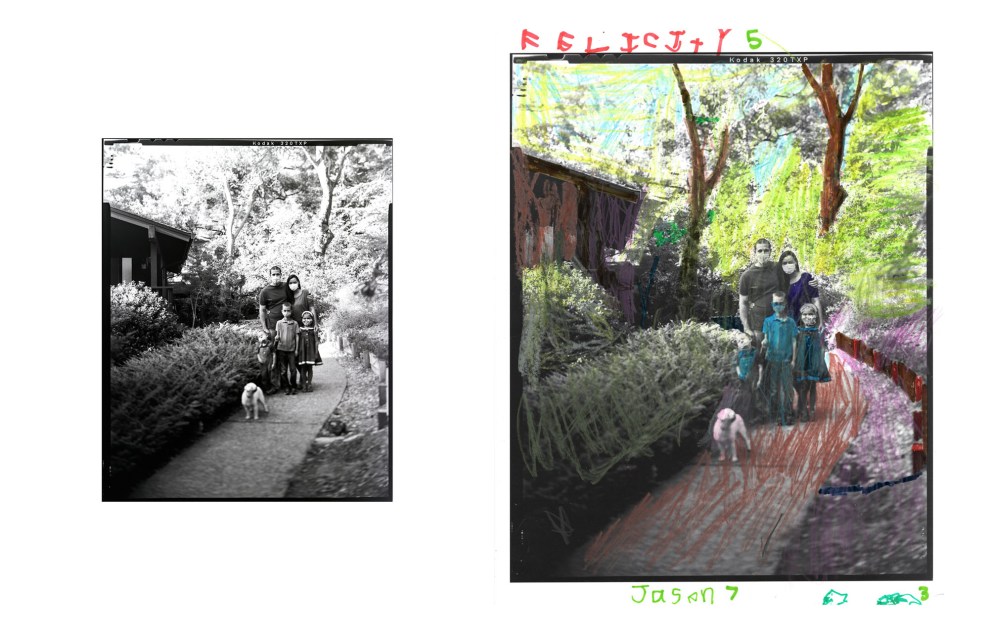

She accomplishes that brilliantly in Front Yard, a pandemic series that portrays families in their yards. After developing large-format slides, she prints them in black and white, inviting each family to color as they like:

A selection of images from Ashima Yadava’s Front Yard series

“This is your story. Do what you want!” she tells them. “Write on it, paint, embellish.” Some faces are pensive and quiet; others are bursting with joy. “Homes are places of love, comfort, fears, and so much more. I see how each family deals with the pandemic differently.”

Yadava keeps the 6-foot distance. “I miss the tactility of interaction. I wasn’t able to hug them, but the exchange of sharing the print and seeing the art they made of it added a bit of cheer.”

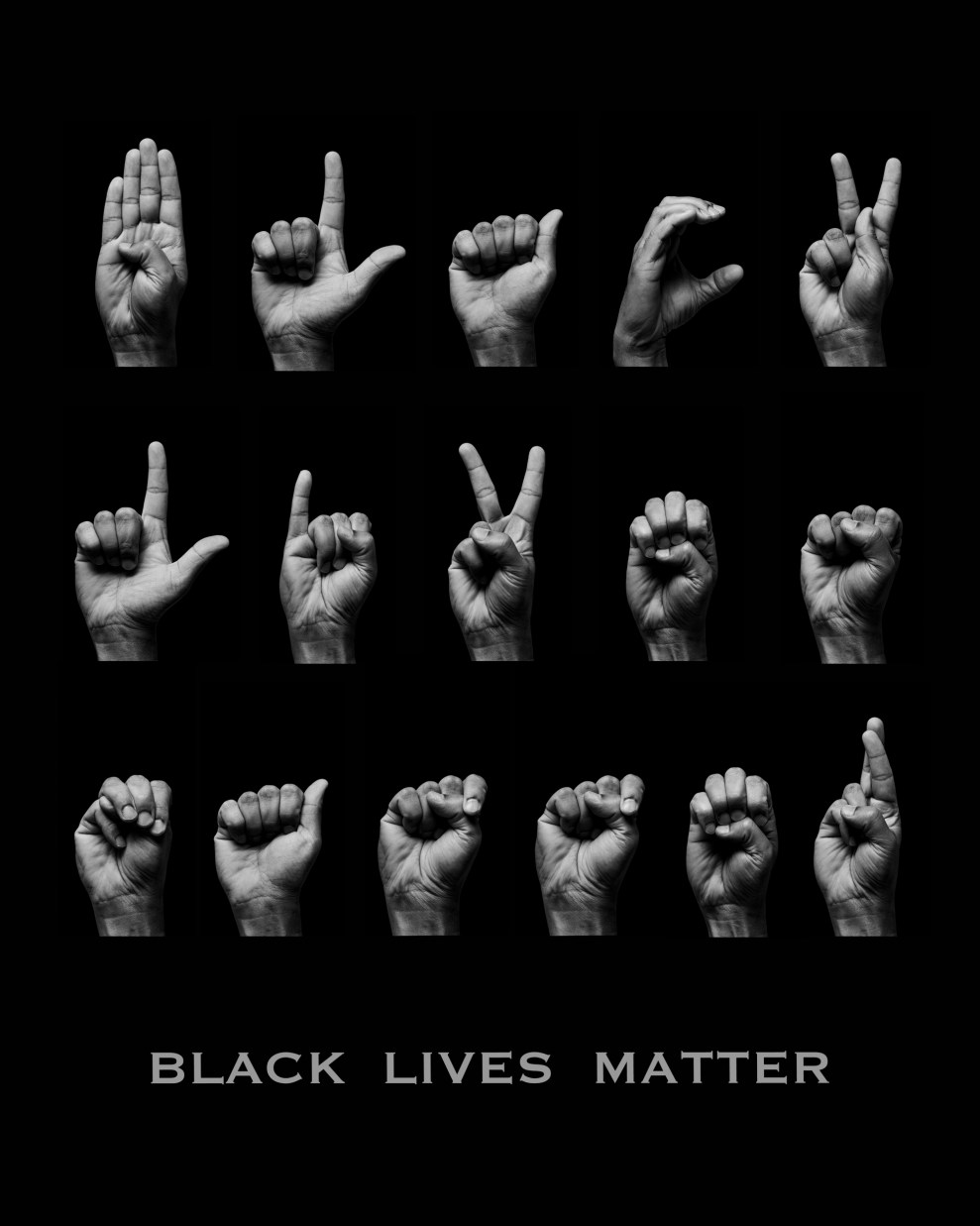

In her latest work, a 40-page zine that’s a photographic representation of “Black Lives Matter” in American Sign Language, Yadava returns to the theme of hands. “The use of ASL not only speaks to this idea of pervasive silence on racism, but also deploys hands as powerful metaphors,” she says. “Hands are in equal part tools of oppression and agents of resilience and revolutionary change.” With the zine, she’s raising funds for grassroots organizations in their fight for racial justice.

“At the core of my work, I’m trying to answer some difficult questions and add to conversations around issues that matter,” she says. “I want to be a creative channel through which these stories are told. Because I have this skill, and if I can use it to amplify these voices, that’s what I’d like to do.”

For more of Yadava’s work, visit AshimaYadava.com. Art inputs in the Front Yard series are by Hamida Banu Chopra, Molly Brennan, Mia Villa, Krish and Mayura Iyer, Shriya Manchanda, Nitya and Arvind Kansal, and the Shade family.

Maitri is at maitri.org and 1-888-8MAITRI (1-888-862-4874). The National Domestic Violence Hotline takes calls 24/7 at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233), or 1-800-799-7233 for TTY. If you’re unable to speak safely, visit thehotline.org or text LOVEIS to 22522. The Department of Health and Human Services has compiled a list of organizations by state.