I know I just remarked on the proliferation of ridiculous Batman tie-in blog posts, attempting to grab some page views from a populace obsessed with this record-breaking film. But I promise this isn’t a cynical grab for your clicks; I’m just pissed off and want to get it off my chest.

I know I just remarked on the proliferation of ridiculous Batman tie-in blog posts, attempting to grab some page views from a populace obsessed with this record-breaking film. But I promise this isn’t a cynical grab for your clicks; I’m just pissed off and want to get it off my chest.

I finally got myself into an Imax screening of The Dark Knight yesterday, and sure, it was enjoyable. The extra-large shots of city skylines were impressive, the effects were well done, and Heath Ledger’s performance was riveting, if only for the creepy back-of-your-mind sense that embroiling oneself so deeply in such disturbing emotions could easily lead one to dangerous self-medicating. But as the film reached its climactic denouement, I found myself getting more and more perturbed at its underlying message, which seemed straight from the office of the Vice President.

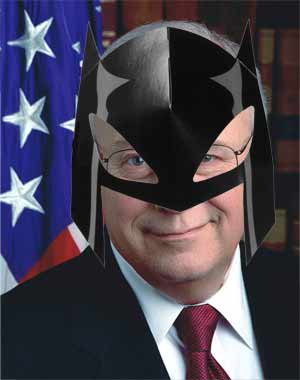

Afterwards, a quick search showed that otherwise–erudite reviews didn’t reflect my concerns, with most critics won over by the film’s expansion of the superhero genre into deeper, darker territory. But what, exactly, was the message emerging from the darkness? Finally, I Googled “dark knight dick cheney,” and I found an article that expressed my feelings exactly: “Batman’s Dark Knight Reflects Cheney Policy.” You go, Washington Independent:

The thought of Vice President Dick Cheney in a form-fitting bat costume might be too much for most people to bear. But the concepts of security and danger presented in Christopher Nolan’s new Batman epic, “The Dark Knight,” align so perfectly with those of the Office of the Vice President that David Addington, Cheney’s chief of staff and former legal counsel, might be an uncredited script doctor. Insofar as it’s possible to view an action movie that had the biggest three-day-opening in cinematic history as a comment on the current national-security debate, “The Dark Knight” weighs in strongly on the side of the Bush administration.

Spoilers follow, so bear with me. Throughout the film, the Joker’s violent schemes are described as inexplicable, pure chaos, the actions of a man who starts fires “just to see them burn.” To fight such an enemy, rules must be broken, and by the end, Batman himself has engaged in some spectacular wire-tapping (listening in on every cell phone conversation in Gotham) and the now-disfigured D.A. has taken revenge on everyone who collaborated, even unwittingly, with the bad guys. Batman proposes a huge cover-up, because, well citizens can’t handle the truth: we need our unsullied heroes, and moreover, we need dark knights to do the dirty work to keep us safe while we can sit back and self-righteously dismiss them as going too far. Sound familiar?

The problem with this scenario is that it’s based on falsehoods. Fox’s 24 ran into similar criticism a while back with their typical setup: a terrorist with the codes to defuse a ticking bomb is found, and only Jack is courageous enough to torture the information out of him. Watching the show, you’re forced to side with the torturer: Jack got the codes, he saved the city, that must be how it works! But of course, not only is the situation completely unrealistic, we also know very well that torture is a terrible way to retrieve accurate information. The only way the neocon worldview makes sense is in a false, exaggerated fantasy world.

In The Dark Knight, the entire premise is based on our villain having no motivation other than chaos: he’s just an evildoer who hates our way of life, which justifies the dark methods of our heroes. But that’s just not how it is. Terrorists are nothing if not motivated, and even if their agenda confuses and angers us, ignoring that agenda is part of the problem. Moreover, it’s infuriating to be told once again that those of us criticizing our leaders are doltish sheep, too stupid and weak to understand their incredible sacrifices, so much so that even our anger is all part of their grand plan to sacrifice themselves for us.

Sure, you can read The Dark Knight as a criticism of our fear-driven society, and of Batman himself, the outlaw obsessive as the pseudo-hero a sick nation deserves. But there’s no way this film is making Batman the bad guy: at the end, after Batman has saved a little boy’s life, blame is shifted to our dark knight and he’s forced to run. “But he didn’t do anything wrong,” cries the boy. It’s a sickening moment, one that reveals the film’s true message: it’s the innocent child whose life was saved that justifies any and every action, and those who vilify our leaders for their methods just don’t understand, not in the way the sweet child does. Unlike Frank Miller’s 1986 graphic novel from whence this film takes its name (and which indicts the corrupt and impotent government), this film seems to laud rule-exempt leaders as the only effective weapons against our evil enemies, a message I thought Americans had finally decided to reject.