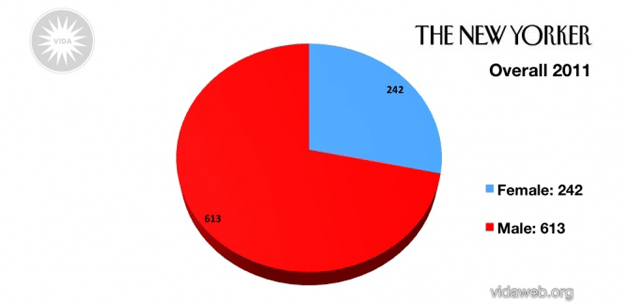

At the New Yorker, women write less than 29 percent of the articles.<a href="http://www.vidaweb.org/the-2011-count">VIDA</a>

Update: MoJo‘s editors discuss the controversy with ASME chief Sid Holt.

They called it the Count, and the concept was simple: Tally up how many women get published in some of the world’s top literary magazines and journals, compare it with the number of men gracing those pages, and slap the results into a pie chart. Red for men, blue for women. The result was a lot of big red pie slices. First published in 2011, they conveyed a clear fact: From Harpers to The New Yorker to The Atlantic, it’s still very much a man’s world. Roughly 65 to 75 percent of the space in the prestigious magazines went to male writers.

The Count is the brainchild of two accomplished poets, Cate Marvin and Erin Belieu. In 2009, the duo founded VIDA: Women in Literary Arts, a nonprofit that acts as part online community, part advocate and agitator for women of letters. The idea, Belieu says, came in a “moment of loathing and terror and revolutionary spark.”

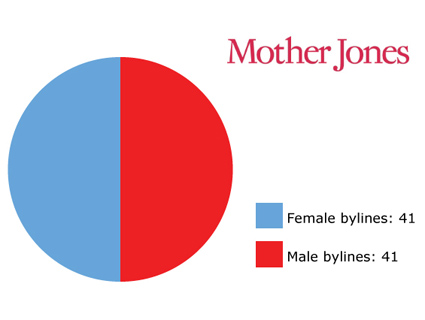

They intended the Count to be a conversation starter, and it certainly has been: After they published the first round, some major magazine editors slammed the numbers as unscientific or meaningless by themselves. Others took them to heart and vowed to work harder for parity. “We’ve got to do better,” New Yorker editor David Remnick said of his magazine’s results. The conversation heated up again this February, after the second tally was published. (Turns out that Mother Jones has done better: We weren’t included in the VIDA tallies, but we surveyed our own print pages and found just as many women as men contributing to them.)

Half of MoJo‘s bylines are women’s. Chart: Samantha Oltman

Half of MoJo‘s bylines are women’s. Chart: Samantha Oltman

And now the problem has once again reared its head: On Tuesday, when the 2012 National Magazine Award finalists were announced, exactly zero women were nominated in the big brass-ring categories—reporting, features, profiles, essays, and columns. (Some women did get nominations in other categories, most encouragingly two nods in public interest journalism, although more typically for pieces about breast cancer economics and “mommy tucks.”) “The National Magazine Awards have sent a pretty clear message,” Belieu says. “When it comes to a career in journalism, chicks should stick to writing about chicks.”

Mother Jones picked Belieu’s brain at a steamy outdoor bar in north Florida. She’s enjoyed some successes in the literary world: A celebrated poet who’s worked with Robert Pinsky, Derek Walcott, and Adrienne Rich, she currently teaches creative writing at Florida State University. She also raises a son—and works at expanding VIDA’s reach in whatever remaining time she has.

Mother Jones: What was your reaction to Tuesday’s National Magazine Award nominations?

Erin Belieu Courtesy photoErin Belieu: Not to denigrate the genuine accomplishments of the small number of women who were nominated, but it’s interesting that they’re acknowledged for what Ann Friedman identifies as “service” writing—the vast majority of their nominated articles concerning “women’s issues”—on breast cancer, under-aged brides, women’s body image. These are all worthy subjects and the nominations are well deserved, but it does beg the question: Do women journalists only want to write about “women’s issues”? Or is that the only thing for which they’re commonly rewarded? Why is it that the nominated men wrote about such a variety of topics that don’t seem to be strictly defined by the equipment they sport from the waist down?

Erin Belieu Courtesy photoErin Belieu: Not to denigrate the genuine accomplishments of the small number of women who were nominated, but it’s interesting that they’re acknowledged for what Ann Friedman identifies as “service” writing—the vast majority of their nominated articles concerning “women’s issues”—on breast cancer, under-aged brides, women’s body image. These are all worthy subjects and the nominations are well deserved, but it does beg the question: Do women journalists only want to write about “women’s issues”? Or is that the only thing for which they’re commonly rewarded? Why is it that the nominated men wrote about such a variety of topics that don’t seem to be strictly defined by the equipment they sport from the waist down?

A friend of mine defines this kind of intellectual segregation as the “tits and nether bits” ghetto, a place in which women only speak to other women. Meantime, men are allowed and encouraged to speak to whomever they want. These issues and questions are ones we at VIDA hope editors may think through in the future when assigning articles to reporters. And we also want to give women writers the confidence to say, “Hey, I can write about whatever I want. I have authority. I have expertise. I have a unique perspective as a person, first and foremost.”

MJ: Give us the background on VIDA and how it started.

EB: Cate Marvin, my co-conspirator, was feeling frustrated with the fact that she had a panel rejected that was the very first feminist panel that she proposed for the annual Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference. She was looking at some of the other panels on new criticism and how to publish a poem, and she just sort of felt like there wasn’t a conversation going on that she could feel good about. She was at her house—she’s a single mother by choice—and she was provoked by folding tons and tons of little tiny infant clothing. She had a gigantic pile of laundry. She suddenly had this vision of herself as the character in Tilly Olson’s “I Stand Here Ironing.“

She had this moment of loathing and terror and revolutionary spark. She hit a level of frustration where she decided to write a now slightly infamous email, saying: “What the heck is going on? Why aren’t women’s issues being discussed, what does it mean to be a writer, why am I the only woman feeling this way?”

I got Cate’s email, and it was an amazing email. The text of it was truly a kind of revolutionary document, and incredibly heartfelt and smart. I stayed up for hours forwarding it to hundreds of people. The next morning her inbox had just collapsed with all of these people who in a 12-hour period had written back to say, “Hell yeah, I feel exactly the same way. What are we going to do about it? Let’s do something.” That morning I got a call from Cate saying, “You’re the one who forwarded this to everyone, you’re going to be my co-conspirator, my cofounder.” I was like, okay, let’s start an organization.

MJ: What else does VIDA do to further the mission?

EB: We’ve spent the last few years building a board of directors, building up an advisory board, teaching ourselves about fundraising, connecting with other programs. In the meantime we’ve been doing the Count, because Cate and I always saw this as one of our central missions. But it’s not enough to just point out the inequity. I think we’re now getting ourselves in a position where we can do some mentoring programs. The first things we really want to work on are mentoring workshops, where we have women mentoring each other. One of the realities for women writers is that sometimes you’ll start strong, but as you see people go up the ladder, working in their literary lives, getting prizes and awards and the better teaching gigs, women tend to sort of drop away. That’s one thing we want to understand.

The other thing that we feel really strongly about is providing VIDAships—we’re not going to call them fellowships. We’re going to put our money where our mouths are and provide financial opportunities that’ll make a difference in women’s lives, provide time and space to do great work.

MJ: Much of VIDA’s work is focused on the creative writerly arts and journals of opinion. Do you see problems among general-interest and consumer magazines, too?

EB: If you go off into general-interest magazines, often women are being shoved aside into various ghettos that perpetuate the problem. Women’s interests are specialized, they’re secondary; they’re somewhere over to the side of the serious work that’s being done. Throughout history, there have been ladies’ magazines, ladies’ journals, and for years there have been women writers who would refuse to participate in women-only sort projects because of that stigma. And you’ve got Peter Stothard at the Times Literary Supplement saying women “are heavy readers of the kind of fiction that is not likely to be reviewed in the pages of the TLS.” He was basically saying, “Women aren’t interested in heavy issues; we do heavy work.”

I know there’s a part of the feminist world that is like, “Hey, screw ’em, we’ll do our own thing over here,” and I can see there’s a value in that. But a kind of nudgy part of me thinks: No. I want access, and I want my daughters to have access to the exact same thing, because we all know there’s no such thing as separate but equal.

MJ: What does the Count tell us, and what can it not tell us?

EB: One of the things that is brilliant about the Count is there’s a gorgeous simplicity to it. There’s something really stunning about those pie charts, right? At VIDA, this was the beginning of the conversation. We did not go into this thinking we knew the answer to something and this was going to illustrate it, because this is a complicated issue. But you can’t deny the starkness of such an incredibly wide discrepancy. We said, wow, this really appears to be of interest. Let’s have a conversation about this, what it means.

It’s been a little bit frustrating for us that people have just wanted to dismiss it. What you’re talking about are people’s unconscious biases. What I’ve learned over the last couple years doing the Count is that I could have Jesus Christ himself come down and say, “Yes, the ladies are right, there is discrimination in the literary world, just as there is in every aspect of life. Gender bias is profound and woven into the fabric of pretty much every part of our lives.” And there would still be all these people in comment boxes and articles saying, “Well, these numbers don’t mean anything.”

Well, maybe we don’t know exactly what they mean yet, but I’m pretty sure they mean something. And it’s not something positive for women writers. Even if it were true that women were submitting fewer pieces then men do, then why is that? Let’s have a conversation about that. Is it because women are inherently slothful? I think anybody who’s ever had a mother knows that that’s not true. Most of the women I know are busting their asses. Working and taking care of a home and, in my world, trying to do their creative work on top of maybe wanting to raise a family and trying to make ends meet. They’re not standing around eating bonbons.

MJ: A similar argument, put forth by the Guardian‘s books editor, is that women have a confidence problem.

EB: For women it is true, so often they don’t want to be seen as aggressive. It’s the double-edged sword that you’ve seen someone like Hillary Clinton face: If you put yourself out there, you’re a bitch, you’re shrill, you’re hysterical, whatever. Maybe it’s true women don’t want to put themselves out there in a critical way because the payback is pretty ferocious. I’m not telling anybody anything they don’t know, but what can we do to change that?

VIDA’s whole mission is predicated on the fact that we’re going to go ahead and believe that people understand it’s important for the world that women’s voices be represented in the mix. For the future. We don’t move forward based on only one half of humanity’s experience. Slightly less than one half, I might add.

MJ: What’s the overall trend? Are things improving for women?

EB: For a lot of women, this is the worst of times. There’s that picture that’s going around the internet of this strong, interesting woman standing there with a sign saying, “I can’t believe I still have to protest this shit.” I wasn’t alive for it, but I have this idea I’m living somewhere around 1967 with this cadre of old white men sitting around telling me what I should do with my body, as if the last 35 years of feminism had not occurred. And it does sometimes feel like a war. I don’t want to toss that word around, but there’s a kind of psychological war on women that’s turning into a legislative war on women.

At the same time, so many of the women that I know aren’t sitting on the fence anymore. I see all of these women, especially younger women, saying: “Yeah, I’m not going to be in the closet about this anymore. I’m a feminist.” All of the women I know are organizing and talking to each other. It just feels like there’s an energy moving in a certain direction. I’m sorry it had to come with these attacks on women’s agency.

You do not want to wake the sleeping giant that is women’s intelligence, ability to organize, ability to multitask. You do not want to piss a lot of women off. For a long time we’ve been taking care of business. While men were being visionary, we’ve been running everything. And we can really jam up the system pretty good.

MJ: Elsewhere, when questions of gender equity in publishing come up, I’ve heard conservatives say, “Oh, please! Mass fiction is a woman’s world, women are readers, they’re the consumers of the media, and as a result media is tailored to their sensibilities.” There are people who say we’ve done a good job of bringing out the Edwidge Danticats, Zadie Smiths, Alice Munros, going back to the ’60s and ’70s.

EB: You wanna make lists? That’s why we count. Look at the presses, at what the lead books are on presses. Look at who wins the awards, who wins the prizes that allow them to have more than an initial career, to have a mid-career and a later career. Do I think it’s changing? The National Book Critic’s Circle Awards just came out, and they were very positive in terms of the number of women who were represented and won. I haven’t counted yet. [Laughs.]

People have a different idea of what it means for women to fully equally participate. Some people see one or two or three women doing well and they say, “There’s not a problem.” Jeffrey Eugenides—and this bums me out, because I really like him—he got up in front of an audience in California and said, “Oh yeah, the thing with women and publishing. I work out…I’m on the elliptical next to a famous woman writer at my gym, so you know, they’re everywhere.” Really? Really? That’s your anecdotal evidence for the fact that there’s some sort of parity?

MJ: Does it make sense to be looking at publication records of these storied, dead-tree publications in an internet age? It seems like Occupy and other phenomena have shown us that if you get locked out, there are so many ways through the door now, online, creating a brand for yourself.

EB: I want that sort of new energy, that new focus. I think we all know that social media and internet magazines have fundamentally rocked the hierarchy of these old gray ladies, as they were. It’s funny that they call them ladies. [Laughs.] But at the same time, I don’t think that’s good enough. There are always going to be gatekeepers, and you always have to keep an eye on the gatekeeper.

Having a poem in The New Yorker means something, for good or for ill, as opposed to the Snotty Rabbit Review or whatever—which could be totally awesome, but at the same time it doesn’t have that kind of impact that allows you to buy the time and make the space to pursue. As writers, you and I know, it all comes down to time and space. If you don’t have your time and space then you just don’t get your work done. The established majors are the tastemakers; they’ve taken it upon themselves to be that. And what they’re telling us about their tastes is that they don’t like women. And they need to.

MJ: David Remnick sounded downright wounded when he saw your stats on The New Yorker.

EB: I like the fact that he just owned it. He didn’t waffle. He was like, “Wow, that sucks; we need to do better.” And I feel like the The New Yorker does that every five years, but it’d be great if they came out and said how they planned to do better.

We’d like to be helpful. We’d like to partner with these places. A lot of editors are like, “So few women writers submit.” Would you like us to put you in touch with some? Because I know a lot of them. I know some fantastic writers. That list is deep, so call me, David Remnick. Call me because we can help, and we want to help.

We don’t want this to be a negative conversation. We want positive gains to come out of it. But you know what? Civil rights made people uncomfortable. Gay rights made people uncomfortable. Sometimes you have to be uncomfortable to change your perspective. If you’ve discovered it’s something you need to care about, then talk to VIDA. We’d love to be of use. That’s what we’re here for.