Education supporters in Los Angeles protest ongoing cuts to education in May 2011.Kevin Sullivan/ZUMA

The Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) released a grim report on Thursday with a pretty simple message: We’re eating our seed corn. Over the past two decades, the number of California high school students completing the state’s most rigorous curriculum—known as the “a-g requirements”—has risen by a third, and the number of high school grads admitted to the state’s CSU and flagship UC systems has risen by a similar amount. That should be good news in a world that increasingly depends on educated workers. But there’s a problem: It hasn’t translated into more students going to college.

According to the PPIC report, state support for higher education over the past two decades has plummeted by a third and tuition charges have skyrocketed to make up the difference. When I attended CSU-Long Beach in the late ’70s, it cost me a little over $100 per semester in tuition and fees. Adjusted for inflation that’s about $300 in today’s dollars. But that’s not what today’s students pay. They pay about $3,000 per semester. UC students pay about $6,000 per semester. The cost of a state university education has skyrocketed 10 times in California.

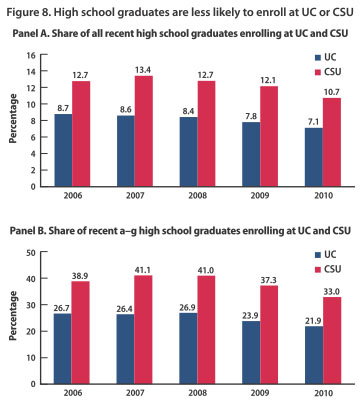

Students can still get loans and grants, of course, but increasingly the out-of-pocket cost is driving students away. And that trend is made worse by CSU and UC policies that have responded to budget cuts by restricting enrollments. PPIC reports  that among all high school grads, enrollment in state universities has declined by nearly a fifth since 2007, from 21.5 percent to 17.8 percent. And here’s even worse news: The enrollment rate among the highest qualified students, those who have completed the a-g requirements, has also declined by nearly a fifth, from from 67.5 percent to 54.9 percent. Both CSU and UC have seen enrollment declines.

that among all high school grads, enrollment in state universities has declined by nearly a fifth since 2007, from 21.5 percent to 17.8 percent. And here’s even worse news: The enrollment rate among the highest qualified students, those who have completed the a-g requirements, has also declined by nearly a fifth, from from 67.5 percent to 54.9 percent. Both CSU and UC have seen enrollment declines.

So what’s happening to these students? Are they going elsewhere? A few are. PPIC reports no increase in enrollments at private California universities and only a small increase in enrollments at community colleges (which have their own budget problems) and out-of-state universities. Their conclusion: “It appears that sizable numbers of high school graduates in California are increasingly less likely to enroll in any four-year college and that a small but notable share of those who were eligible and even accepted into UC and CSU do not attend college anywhere.”

Declining state support for higher education, of course, is not a phenomenon limited to California. And if the same thing is happening elsewhere, it means that a sizable number of students who have graduated during the Great Recession are simply choosing not to go to college even though they would have done so in better times. The combination of a tough economy and rising costs has shut them out of a college degree.

It’s hard to think of a more self-defeating social policy than this. Temporary economic downturns aside, we know that we desperately need more college graduates in the future. But instead we’re doing everything we can to turn out fewer of them, and in the face of this congressional Republicans are playing dumb games with legislation to keep student loan interest rates affordable—surely the absolute minimum response we could expect from our elected leaders.

Twenty years from now we’ll all be arguing about why the Chinese or the Koreans or the Indians are eating our lunch on the global stage. But why wait 20 years? The answer is right here in front of our faces today.