In a shabby, low-slung bungalow on the grounds of California’s San Quentin State Prison, Adnan Khan sits nervously in front of a microphone. A slender 33-year-old with dark, slicked-back hair and skin the color of cinnamon, he’s clad in typical prison fashion—jeans, powder-blue button-down over a white T-shirt, standard-issue dark jacket. To one side, inmate Antwan Williams sits at a workstation wearing headphones while fellow prisoner Earlonne Woods and longtime San Quentin volunteer Nigel Poor—Williams’ co-producers on the hit podcast Ear Hustle—prepare for Khan’s interrogation.

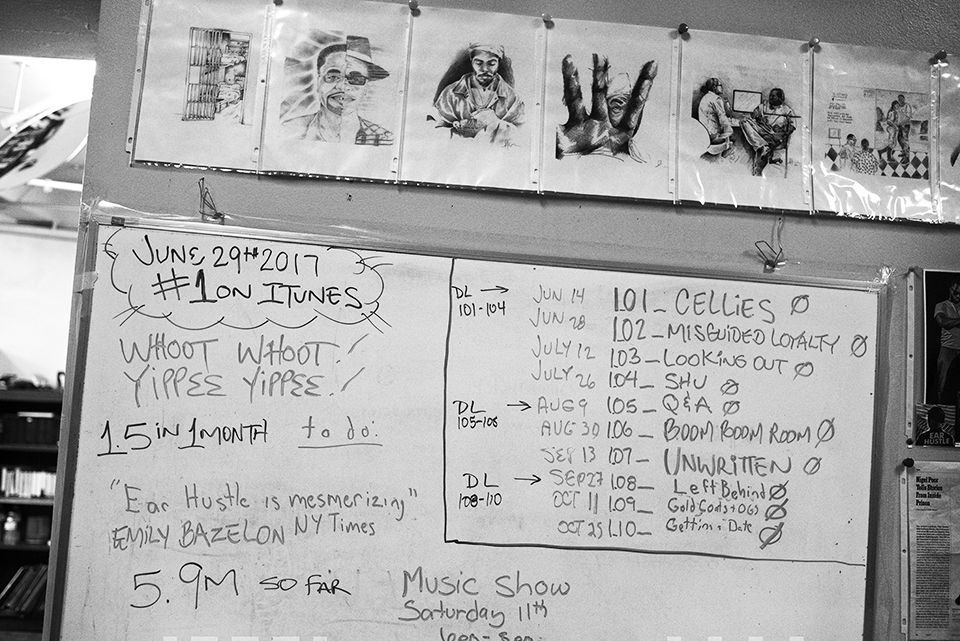

A whiteboard still displays the first season’s episodes, with one date highlighted: June 29, 2017—the day Ear Hustle hit No. 1 on iTunes after it was featured on the Today show. A second whiteboard lists new potential topics, such as “ministering on death row” and “gangsters and literature.” Today’s session is for an episode on “prison firsts” that will air during the podcast’s second season, which launches on March 14.

Khan’s story, at its heart, is about estrangement. At 18, he took part in a robbery in which his partner fatally stabbed a man. Khan got a sentence of 25 years to life. He’s here to talk about the day a few years ago when his mom first came to visit him in prison.

Poor, who teaches photography at California State University-Sacramento, gets things started. Her tone is soft yet deliberate: “How did you prep for your interview with your mom?”

“I took a lot of deep breaths,” Khan says, and then adds, almost as an aside, “I tried to choreograph my hug because I haven’t hugged my mom in a long time.”

A white board shows last season’s podcast schedule—and one very special date.

Mark Murrmann

This piques everybody’s interest. It turns out that Khan hadn’t hugged anyone during his decade-plus inside. He’d actually forgotten how to do it. Should his arms go around his mom’s shoulders? Her neck? He practiced in his cell by giving himself air hugs, but in the end, he let her lead. His shoulders were tight, his body like a steel rod. The hug didn’t have “too much grasp,” he adds, and he felt like a robot. But his mom held on and wouldn’t let him go.

Ear Hustle stands out in the podcast realm for its textured stories about men coping with the challenges of incarceration. One episode unpacks how San Quentin’s unofficial party planner navigates the unwritten rules of race. Another covers intimacy in prison and highlights how nerve-wracking it is for guys to prepare for the tenderness of a family visit after having to act macho for so long. Woods, stocky with a shy smile, is 19 years into a 31-to-life sentence for attempted second-degree robbery. He plays the role of tour guide, alternating lines with Poor and explaining to listeners how things work in prison—”ear hustle,” he notes in the debut episode, is prison slang for “eavesdropping.” Williams, the athletic-looking sound designer, works behind the scenes to compose the music and edit episodes. At 29, he’s served 10 years of a 15-year sentence for armed robbery. The first season, Poor tells me, has attracted many thousands of letters and emails from fans ranging from high school kids to district attorneys.

Ear Hustle co-host Earlonne Woods, who is serving 31 years to life for attempted second-degree robbery, deals with some production tasks.

Mark Murrmann

Julie Shapiro, executive producer for the podcasting outlet Radiotopia, knew Ear Hustle had potential the moment she first heard it. That was back in 2016, when Poor caught wind of Radiotopia’s talent-seeking contest. The prisoners she worked with were already considering a podcast, and so, basically on a lark, the three put together the required audio samples and ended up winning. Radiotopia rewarded the project with a distribution deal and funding they used to acquire high-quality production gear. “Their pilots,” Shapiro told me, “showed the promise for a very sophisticated, nuanced, sensitive, humorous way of telling stories—from a place where you wouldn’t suspect any of that.

Woods says he knew the idea would be a hit. When he first met Shapiro, he bragged that Ear Hustle would get 1 million downloads. Shapiro was skeptical, but season one ended up with 7.2 million. “There’s always something in a story that somebody can relate to,” Williams explains. “We’re still human. We still experience grief, pain, love, the desires of life. We still go to work, school. It’s just in a smaller microcosm.”

Antwan Williams, sound designer and co-creator of Ear Hustle, is serving a 15-year sentence for armed robbery. He composes all the music for the podcast.

Mark Murrmann

Producing a podcast in prison is more complicated than it is on the outside. You work when you’re allowed to and include what the authorities say you can. Each completed episode is submitted on a CD-ROM to Lieutenant Sam Robinson, San Quentin’s public information officer, for approval—a process that can take anywhere from hours to a week. Robinson says he has yet to shoot down an episode, but there’s no question who’s in charge. Last August, production was suspended for nearly three weeks while the facility went on lockdown. “There’s no investigative journalism in prison,” notes former inmate Troy Williams, who hosted a show called the San Quentin Prison Report during his incarceration.

Near the beige administration building, visitors encounter a second checkpoint where they show ID, get a hand stamp, and proceed through an ancient-looking iron gate into an impossibly lush courtyard flanked by a medical center and a chapel built in the same style. Were it not for the hulking stone building in the distance (death row), it would be easy to forget you were at a prison. Located on the San Francisco Bay in pricey Marin County, San Quentin is a study in jarring juxtapositions. To get there, you drive through San Quentin Village—a long road with quaint single-family homes (former staff housing) where middle-class white folks walk their dogs. The road ends at the prison’s perimeter gate.

Woods and co-host Nigel Poor interview a prisoner on the yard.

Mark Murrmann

As Woods explains in one episode, inmates would much rather be here than at other facilities—say, Folsom or (God forbid) the notorious Pelican Bay prison. San Quentin, which houses both medium- and maximum-security inmates, boasts a wealth of programming. There are college-level courses through the Prison University Project, a baseball team, coding seminars, yoga classes, and the multimedia program that gave birth to Ear Hustle. These activities, plus San Quentin’s proximity to an urban center, make it a destination for volunteers and luminaries. The NBA’s Golden State Warriors stop by every year—photos of coach Steve Kerr grace the walls of the multimedia studio.

There’s also an impressive journalism program. San Quentin News has been around since the 1920s. In 2009, Discovery sponsored a filmmaking class at San Quentin and donated the gear afterward. In 2015, a chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists was established here. The San Quentin Prison Report partnered with San Francisco public radio station KALW to broadcast stories about inmates with HIV and what it’s like to live through a cellblock riot. Former host Troy Williams views prison media as a vehicle for organizing the communities of color devastated by cycles of crime and punishment. Partly for that reason, he has been critical of Ear Hustle: “There’s no way a white woman who has never been incarcerated can be the voice of black men inside a prison,” he told me. “We don’t need a translator.”

Co-host Poor, who teaches photography at California State University, is a volunteer in the prison media lab.

Mark Murrmann

Poor seems sympathetic to the critique, but she’s adamant that Woods and Antwan Williams run the show. “The whole premise is to tell the everyday stories of life inside prison, and they’re told from the perspective of the people living it,” she says. For Williams, the chance to contribute to the public conversation is a key attraction. “The biggest thing that lacks in our society today is dialogue,” he says. “We believe we know where somebody is coming from, and we can be completely wrong.”

Woods gathers ambient sound on the yard for an upcoming episode.

Mark Murrmann

Woods and Williams are justifiably proud of their success, yet it raises a question: Who benefits? Working in the media lab earns inmates standard prison wages—less than $1 an hour—and California state law forbids inmates or volunteers from profiting directly from their media endeavors. (For now, Radiotopia uses the show’s sponsorship and donation income to cover production expenses—about $30,000 for season one, according to a corrections department spokeswoman.) While a parole board might view the men’s work favorably, that prospect is years away.

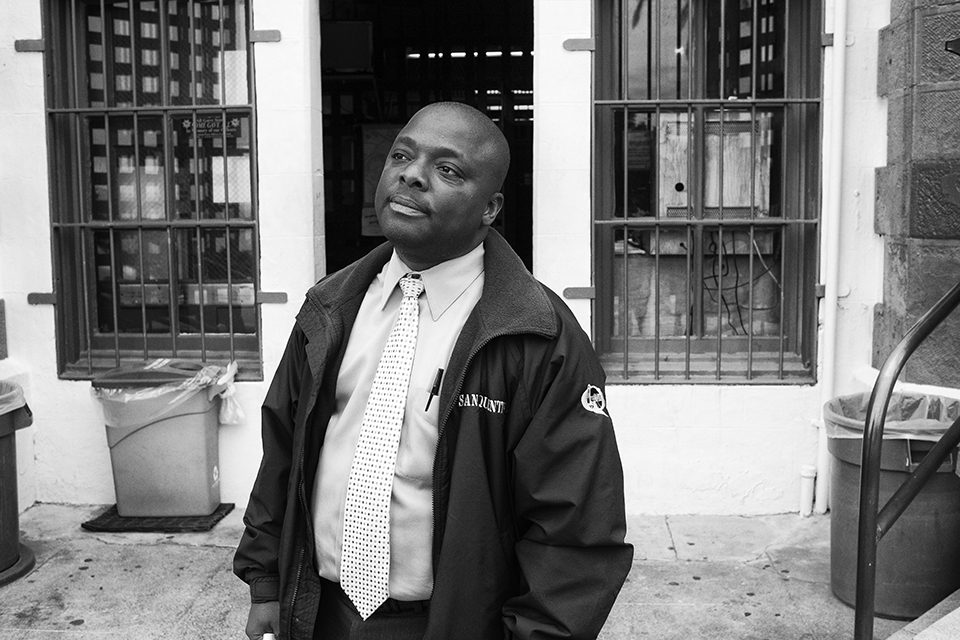

Lieutenant Sam Robinson, San Quentin’s public affairs officer, signs off on each podcast episode.

Mark Murrmann

There are intangible benefits, though. “I think it’s cool, especially when your mother can tune in and listen and give you her comments on what she thinks or things she didn’t know about,” Woods says. Add to that the outside connections—all that fan mail!—the busted myths, and the enhanced public understanding of whom we’re keeping in cages and why, and how it affects people’s lives inside and out. “It’s overwhelming at times, but I think it’s worth it,” Williams tells me. “We’re still in here. Our day-to-day lives haven’t changed. We have to be okay with being in here and still producing something that a lot of people enjoy.”