Robert Franklin/AP

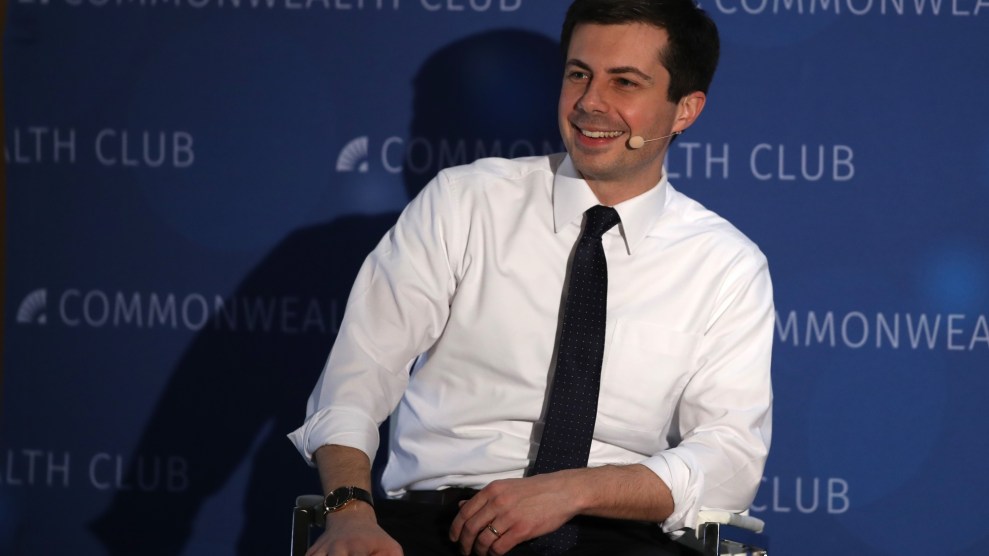

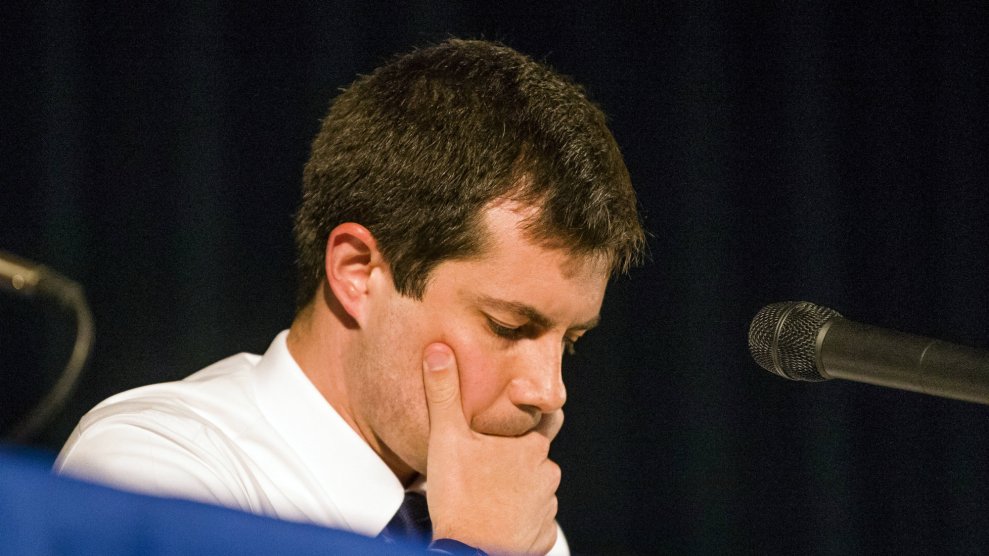

Mayor Pete Buttigieg appeared to be overwhelmed as he stood on stage with his chief of police at a South Bend, Indiana, town hall in June. Buttigieg had abruptly left the campaign trail after Sergeant Ryan O’Neill, a white cop, shot and killed Eric Logan, a 54-year-old black man. O’Neill had been responding to a call about a suspicious person breaking into cars when he came across Logan inside a vehicle. According to O’Neill, when the officer confronted Logan, he approached him with a knife; so he fired his gun twice, killing Logan. The officer’s body camera was turned off and the shooting sparked local outrage. Buttigieg’s constituents were loudly voicing their frustrations with the city, the mayor, and his police department. “Reorganize your [police] department by Friday of next week,” someone in the audience demanded. “Get the people that are racists off the streets.”

Buttigieg told the crowd that he’d been trying to fix the police department. “I promise you,” he said. “We have tried everything we can think of.”

This was not the first time the community had clashed with police, but it was the most public instance, occurring in the midst of the two-term mayor’s presidential campaign. Starting before Buttigieg’s tenure as mayor and throughout his seven years on the job, the relationship between black residents and the South Bend Police Department has been tense, a relationship that it appears Buttigieg had done little to improve. But this shooting also brought to light a rift between Mayor Pete and South Bend’s black community.

“The many well-intentioned steps we have taken, locally and across the country, have not succeeded,” he said in an email to supporters after the town hall. “We have not done enough.”

It’s a story replicated across the country in big cities such as Baltimore and small towns including Ville Platte, Louisiana. What distinguishes South Bend, aside from the fact that its mayor is running for president, is that black residents and black police officers have similar complaints about the police department that serves their town. During Buttigieg’s tenure, several officers have alleged that their white superiors have discriminated against them, which has resulted in even greater mistrust between the community and the police department as a whole. That strain is reflected in the numbers. When Buttigieg became mayor in 2012, there were 29 black police officers in South Bend. By 2019, that number had dwindled to 15. Mayor Pete has presided over a police department that’s been roiled by internal tension and has been at odds with the black community. More to the point: He’s done little to resolve it.

“When these issues continually happen, it shows that there’s definitely a problem,” Alfred Titus, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, tells Mother Jones. “The community feels as if they’re not going to get a fair shot.”

But as Buttigieg wowed pundits and reporters with his knowledge of multiple languages, and his piano talent, little national attention was paid to the way he handled a number of police department scandals and how his relationship with the black community frayed. According to Mayor Pete’s campaign, however, he has attempted to address the problems in the police department in several ways over the past few years. He appointed a majority black civilian police board, he said, “to make all the decisions in police discipline.” After realizing that one problem in recruiting diverse officers was the physical fitness test, he restructured the application process so that potential recruits would be able to take a practice test before the official one in order to be more prepared. The results of a structural review of the SBPD he mandated in 2017 found that community policing should be increased, and that all police officers should engage in civil rights and “implicit bias” training. Mandatory body cameras were added for the 170 officers in the patrol division in 2018. When making that announcement, Buttigieg noted that the body cameras would reinforce the message that, “This city is a safer place and a better place to live when officers and neighbors know they’re all on the same side.”

Buttigieg is on his third police chief. When he assumed office in 2012, he inherited Darryl Boykins, the first black person to serve as police chief, who had been appointed in 2008 by then-Mayor Stephen Luecke. After Boykins was accused of illegally recording white police officers allegedly making racist remarks about him in 2012, he was investigated by the FBI for violating wiretapping laws. He denied the allegations, but Buttigieg demoted Boykins, and he later resigned. Litigation over whether the tapes should be made public is still pending. The contents of the tapes remain publicly unknown. Boykins was replaced by Ronald Teachman, a white police officer.*

In 2014, a group of black officers went to the police department’s human resources to complain about Teachman. “Some of our primary concerns is the lack of diversity on the police department, and what we have noticed, and what we are now claiming to be blatant racism by Chief Teachman and his administration,” Sergeant Nathan Cannon said at the time. Titus points out that the dynamic that Cannon described crucially eroded the trust of the community “in their police department—and their government.”

With little or no action after these complaints by the Buttigieg administration, police officers began to file a number of lawsuits. Things only deteriorated after Teachman resigned in 2015 and Buttigieg replaced him with another white officer, Scott Ruszkowski. Because the suits allege a discriminatory pattern over the course of a few years, both chiefs are named in the lawsuits.

The four suits filed by black police officers between 2015 and 2017 follow a similar pattern: Black officers alleged they were repeatedly passed over for promotion in favor of less-experienced white officers. Two of the cases were dismissed, one was resolved in mediation, and another is pending.

In April 2016, for instance, Lieutenant Marcus Wright filed a suit against the city and the police department alleging that he had been denied a transfer to the more desirable day shift. Lieutenant Wright claims that he was subjected to an interview for a rank he already held and then three non-minority officers with a lower rank were then promoted to day-shift lieutenants. The suit also claims this violated a policy that should have granted him the transfer before giving the shift to officers who had just been promoted. The case was resolved in 2016 by mediation.

In 2017, South Bend Police Officer Davin Hackett sued the police department over another allegation of racial discrimination. Hackett, a black man, has been an officer in South Bend since 2006. Before becoming a police officer, Hackett served in various branches of the US military and is currently in the US Air Force Reserves. Because his military experience gave him firsthand knowledge of working with bombs and missiles, Hackett applied to the police department’s bomb squad in 2014. His application was denied. According to the lawsuit, the reason behind the denial was that his active military status “might cause him to be absent for necessary training.” But Hackett alleges that it was because he’s black. He filed complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Department of Labor. The following year DOL informed him that SBPD reversed course and assigned him to the bomb squad.

But in Hackett’s suit, he asserts that he has not received bomb squad training, participated in any of the special squads activities, or received additional pay for bomb squad duties. He also filed a complaint with the EEOC alleging that he’d been denied a promotion and was passed over in favor of white men who were less qualified. The suit says that since filing the complaints, both Teachman and Ruszkowski retaliated against him by “subjecting him to a battery of unjustified investigations and discipline.” The case is still pending.

After Michael Brown had been shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 a national conversation about police violence in black communities made many Democrats embrace a generation’s rallying cry: Black Lives Matter. To counter the idea that some police officers were operating with impunity, conservatives responded by declaring “all lives matter.” In 2015, while the police department was embroiled in these accusations and with tension with community members still high, Buttigieg opted to use conservative language when talking about South Bend’s police problem, which boiled down to saying that it was possible to both respect the risks police officers take and fight implicit biases. “We need to take both those things seriously,” he said, “for the simple and profound reason that all lives matter.”

Women police officers also faced problems in the department, and there have been allegations of sexual harassment. In 2015, former police officer Joy Phillips, a white woman, filed a lawsuit alleging that she had been denied promotions and retaliated against for speaking to her supervisors about “demeaning remarks, sexual innuendo, and unwanted sexual advances” by her colleagues. Phillips claimed that when she applied for a higher-ranking position, Teachman instead promoted three men who had less experience and “serious disciplinary violations.” When Phillips complained to her supervisor about unwanted sexual advances, she said, she was investigated for “defaming a fellow officer.” At trial in 2017, Phillips’ lawyer Dan Pfeifer maintained that her superiors were targeting Phillips. “They were out to get her,” he said. “They were going to drive her out of the police force.” Phillips won her case, and she’s now an investigator at another Indiana police department.

Mayors are frequently blamed for the failings of their police departments. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio ran in 2013 on a platform of police reform, but critics have said his efforts were not enough. Officer Daniel Pantaleo killed Eric Garner by putting him in a chokehold in 2014, and five years later, Pantaleo will not face any criminal charges. Garner’s family is still waiting to see if the officer will face any disciplinary actions within the police department. Critics blame Mayor de Blasio for inaction on the case.

Similarly, Titus notes, Buttigieg had significant sway over the police department. “He has the power to make the changes necessary to fix the problem,” he says. “He has the ability to speak with them and exercise his suggestions.” The lawsuits indicated that there was a serious problem within the police department and that if black officers were alleging discrimination, how were black residents supposed to have faith that their police department would treat them fairly? But Buttigieg waited until he was under the national microscope before tackling an issue that’s been plaguing his community for years.

His campaign, however, said that Buttigieg worked to improve the inner workings of the police department. “Under Pete’s leadership, the South Bend Police Department has directly addressed decades-long issues, including transparency, discipline, bias, use of force, recruitment and promotion,” spokesperson Chris Meagher tells Mother Jones. “Under Pete’s direction, SBPD has instituted comprehensive internal record-keeping for personnel and Internal Affairs.”

At the town hall, one resident confronted the mayor. “You’re running for president and you want black people to vote for you?” she said. “That’s not going to happen.” The problems with the South Bend Police Department revealed to a national audience that Buttigieg’s relationship with the black community was strained in a number of ways. In an effort to address those concerns, last week Buttigieg released the Douglass Plan, named after famed writer and slavery abolitionist Frederick Douglass, which seeks to dismantle “racist structures and systems.” It touches on several issues important to black voters, including the criminal justice system. On policing, the plan stresses police accountability and eliminating discriminatory practices driven by racial bias. Buttigieg’s plan also says that as president he’d support departments that “actively strengthen community relationships,” including those that hire diverse officers, and departments that “effectively” respond to officer misconduct. It might be best to start at home.

* Correction: This article was revised to reflect the fact that it is unknown whether the recordings captured alleged remarks.

Clarification: This story has been revised to include additional information regarding steps Buttigieg has taken regarding the South Bend police department.