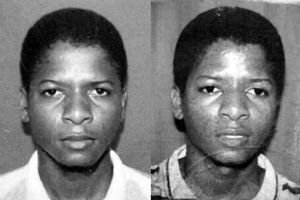

FBI/Zumapress.com

Read Karen Greenberg’s previous coverage of the trial of Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani, the first Guantanamo detainee to be tried in a civilian court.

Wednesday marked the end of the witness and testimony phase of the trial of Ahmed Ghailani, who stands accused of participating in the bombing of the US Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998. As Judge Lewis Kaplan remarked early in the week, the trial was advancing at “lightning speed,” largely due to his insistence that both prosecution and defense stay concise, on point, and efficient. Still, Wednesday’s milestone was not as remarkable as a small hearing held on Tuesday, a session that was rife with both intense debate and good humor—the tone Kaplan has set throughout. In the absence of the jury, the defendant, and the gallery of victim observers, the judge and counsel were discussing witnesses—FBI agents and Tanzanian police officials—whom the defense wanted to bring back for purposes of impeaching testimony they had previously given. The defense has tried to assert over and over in cross-examination that the testimony in this trial contradicted what these and other witnesses originally told the FBI. Over the course of nearly four hours, going over the defense’s requests “statement by statement,” Judge Kaplan reasoned his way through each one, regularly interjecting his thoughts about memory and translation and their impact on this landmark trial.

The problem of memory has plagued this trial from the beginning. As an FBI witness testified on Monday about his 1998 search of Ghailani’s residence, the jury repeatedly heard, “I have a vague recollection…I don’t recall…I don’t remember…I do not know…. I am searching my memory.” It has been a refrain echoed by witness after witness, both American and Tanzanian. But try as defense attorney Peter Quijano might to suggest that witnesses were merely “feigning a lack of memory,” the judge pointed out that it is just plain difficult to remember the details of events 12 years ago.

But more than memory was at issue here. The judge stepped outside the arena of memory to one that he has mentioned on several occasions in this case—the matter of translation. He has expressed concern on occasion about how exactly the FBI had questioned Tanzanians—the answer generally was: with Tanzanian police translating. During the hearing on Tuesday, Kaplan was blunter, noting that “For all we know [a witness] could have been reciting Willie Mays’ batting average,” given that FBI agents spoke no Swahili. Defense counsel Quijano was quick to point out that if this was true for one witness, it could be true for all of them.

The exchange once again evoked a question that had been lingering in the trial, yet has never been asked outright. What does it actually mean to try a case with evidence and testimony from a culture so far removed from the context of an American court of law? Several times, when a Tanzanian witness has been sworn in—raising his hand uncustomarily high, looking at no one, on occasion asking “Do I pledge?” to which Kaplan has responded, “Just say yes or no”—there has been a moment of poignant discomfort. Questions about memory and translation are merely symptoms of a larger issue—the distance in both time and space between the United States and Tanzania.

The sense of cultural disconnect has been apparent in the evidence as well. For example, much was made by the defense about the way in which the airport officials may have allowed terrorists go through airports without security checks, but what do we really know about airport scrutiny in general in Tanzania now—let alone as it existed in the 1990s? How, too, should the jury interpret the ways in which characters in this trial’s narrative are alleged to have shared phones, bedrooms, and work? How much of this is conspiracy versus common practice in a culture of poverty and extended family connections? What do any of these things mean in context, and who can be trusted for an answer?

Ghailani’s trial may indeed demonstrate that federal courts are the appropriate venue for prosecuting Guantanamo detainees. His case was chosen for its symbolic value, not for the nuance of its specifics. One hopes that in future terrorism trials, where the federal courts may be under less pressure to prove that they can handle these cases, there won’t be as much need to demonstrate efficiency. Instead of ignoring questions of cultural difference—and seeing memory and translation as impediments rather than as windows onto larger questions—prosecutors, defense counsel and judges may be able to explore the collision between US standards and those of a foreign culture. For now, bringing the trial to its ending swiftly and with the agreement of all parties, stands as an achievement in itself.

Additional research by Lisa Sweat, Brian Chelcun, and Christine Yurechko of the Center on Law and Security.