Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Nailing down the motive behind a mass shooting is often difficult. Most shooters tend to be driven by a poisonous blend of entrenched grievances, personal setbacks, depression, rage, suicidal urges, and in some cases, serious behavioral disorders or mental illness. Rarely can their actions be explained definitively by a single factor. However, Mother Jones’ in-depth database of mass shootings reveals a stark pattern of misogyny and domestic violence among many attackers. This factor is already relatively well known in cases where men gun down intimate partners, children, and other family members in their own or other people’s homes.

There is also a strong overlap between toxic masculinity and public mass shootings, according to our latest investigation.

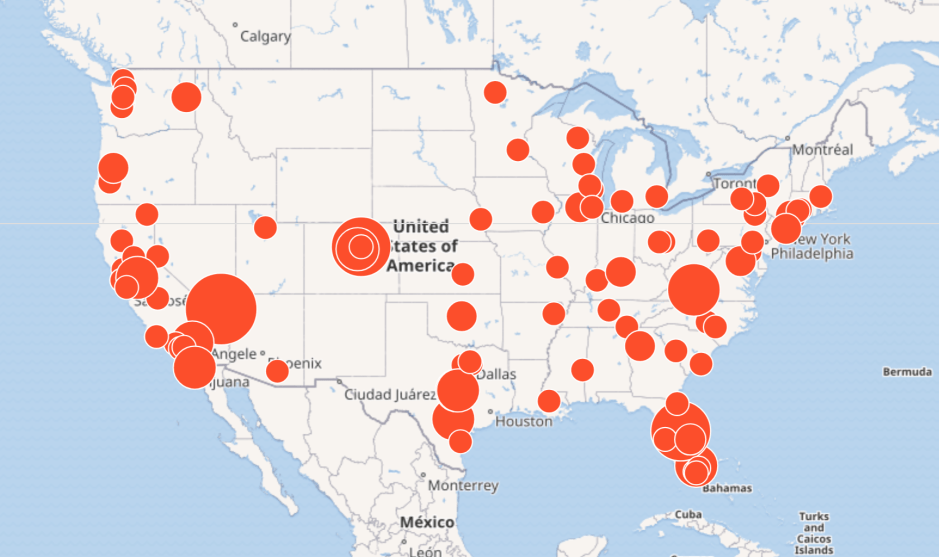

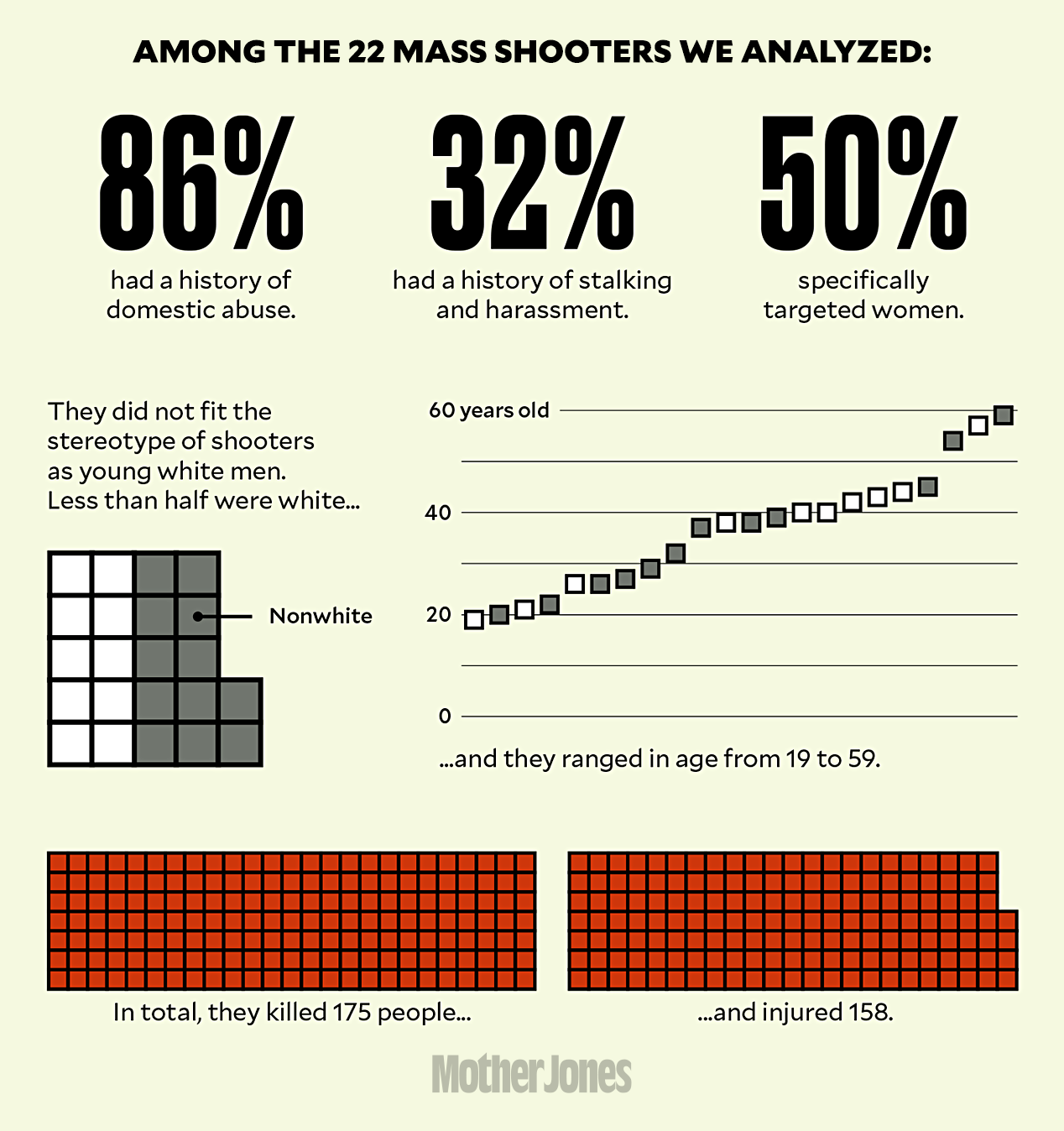

Based on case documents, media reports, and interviews with mental health and law enforcement experts, we found that in at least 22 mass shootings since 2011—more than a third of the public attacks over the past eight years—the perpetrators had a history of domestic violence, specifically targeted women, or had stalked and harassed women. These cases included the large-scale massacres at an Orlando nightclub in 2016 and a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, in 2017. In total, they account for 175 victims killed and 158 others injured. Two of the shooters bore the hallmarks of so-called “incels”—a subculture of virulent misogynists who self-identify as “involuntarily celibate” and voice their rage and revenge fantasies against women online. A man who recently planned to carry out a mass shooting in Utah and another who opened fire outside a courthouse in Dallas also appeared to be influenced by incel ideas.

Two recent cases show how violent misogyny and abuse against women can fuel mass shooters’ behavior—and may serve as warning signs long before they strike. As observable indicators of a person’s capacity for escalating violence, this information could help mental health and law enforcement experts who work to prevent mass shootings by using behavioral threat assessment to identify and intervene with potential attackers.

Scott Beierle was a socially maladjusted 40-year-old with a history of arrests for groping women in public. As far back as high school, he’d written detailed fantasies about raping and murdering women. At Florida State University, where he attended graduate school, he alarmed people around him with inappropriate comments and stalking behavior and was eventually banned from campus. In videos he posted on YouTube, he expressed anger toward women and admiration for Elliot Rodger, a suicidal mass shooter who targeted sorority members in Southern California in 2014. By last November, Beierle had hatched a plan to attack a yoga studio in Tallahassee. As an evening class began, he posed as a customer carrying a yoga mat. Once inside, he opened his bag, put on a pair of noise-muffling headphones, and pulled out a handgun. He fatally shot two women and wounded four other people, then used the gun to kill himself after a person in the class rushed him and fought back as others fled.

About three weeks later in Chicago, 32-year-old Juan Lopez approached his ex-fiancé, Tamara O’Neal, outside the hospital where she worked as an ER doctor and demanded that she give him back an engagement ring. At the time, Lopez was still involved in a protracted custody battle with his ex-wife, who had secured an emergency protection order against him after he menaced another person with a gun and threatened to show up at her job to “cause a scene,” according to December 2014 court records. “I fear that my safety is in jeopardy,” she said. Four years later, Lopez fired a pistol at O’Neal from point-blank range, then shot her again as she lay in the hospital parking lot. He then entered the building and killed two more hospital employees before dying in a gun battle with police.

The trail of violent misogyny and abusive behavior in many shooters’ cases dovetails with a key finding from research published by the FBI in 2018: Not only do most shooters give off multiple behavioral warning signs that are observable to people around them, a majority do so starting months and even years before their attacks. The shooters in Tallahassee, Chicago, Orlando, Sutherland Springs, and elsewhere brutalized women long before their gun rampages. These patterns are significant to threat assessment professionals, who are trained to gauge how dangerous a person may be by analyzing a range of possible warning behaviors, including a history of violence, acquisition of weapons, and signs of further violent intent.

Years before he fatally shot O’Neal and two other people, Lopez, like many domestic abusers, had used threats of violence to exert control over his ex-wife. Brandishing a gun and threatening to go after her at work were indicators of Lopez’s capacity to plan and carry out an attack, according to a threat assessment expert familiar with the case. Lopez’s record with women contained other warning signs: He had been kicked out of a fire department academy after inappropriately touching female cadets and roughing them up during training exercises.

In the years before Beierle struck, he expressed his misogyny and grievances in verbose YouTube monologues. He delivered his pseudo-intellectual and narcissistic screeds mostly in a calm, articulate manner. But his smoldering rage against women was not far from the surface: He seethed in moments when he called out several young women who he claimed had wronged him during his school years. As he recounted how one stood him up for a date, he paused briefly for a nonchalant but chilling aside: “Ah, I could’ve ripped her head off.”

Naming names may have been tantamount to Beierle making a hit list, a common behavior among shooters, though ultimately he targeted women he did not know. “The treachery that a female is capable of…to me is astonishing,” he said. “What comes around goes around, and those that engage in treachery ultimately will be the victims of it.”

According to a Washington Post investigation, Beierle had also written reverently about a trip he made to the site of the Tallahassee boardinghouse where serial killer Ted Bundy once lived, and to the sorority row where Bundy had murdered two women in 1978. Such a pilgrimage-like act, seeking inspiration from a place associated with infamous violence, is another behavior seen among various rampage shooters.

Mass shootings are a small fraction of overall gun violence in the United States, but their steady repetition is grim. Mass murders where men kill their female partners and children occur nearly two dozen times per year, according to a 2013 study in the Journal of Family Violence. The public attacks by men who targeted or brutalized women that we analyzed for this investigation average out to about three per year. Moreover, hundreds of other women are shot to death annually in individual murders or murder-suicides by male intimate partners.

Existing federal law prohibits people convicted of some domestic violence crimes from owning or possessing guns, and some states have passed laws in recent years to strengthen such regulations. The Justice Department has also been cracking down recently on domestic abusers who unlawfully keep guns. But many states with looser gun restrictions still allow misdemeanor domestic-violence offenders to have firearms, including abusive partners who are not spouses, a problem known as the “boyfriend loophole.”

In Florida recently, a woman fearful of her estranged husband was arrested on robbery charges after she took his guns and turned them into the police—even though he had just been jailed for alleged violence against her, was subject to a temporary restraining order and was prohibited from having guns as a condition of his release on bail. A local law enforcement official said that the gun prohibition was difficult to enforce and essentially would have required the husband’s voluntary compliance: “It’s one of those things you hope people do the right thing and surrender their guns.”

As part of an attempt to reauthorize the federal Violence Against Women Act this spring, House Democrats sought to broaden gun restrictions for domestic abuse and stalking convictions and close the so-called boyfriend loophole. But the National Rifle Association and their allies have stood in the way, with Majority Leader Mitch McConnell so far burying the bill in the Republican-controlled Senate. Gun lobbyists have long pursued similar goals in statehouses. Opposing a recent effort in Rhode Island to strengthen gun laws against domestic abusers, the NRA acknowledged that domestic violence is “abhorrent”—but argued that some men are falsely accused of abuse and could have their gun rights trampled.

As the NRA opposed the Violence Against Women Act this April, a spokesperson reiterated the group’s opposition to tighter gun restrictions for known abusers: “The fact that Nancy Pelosi and her minions of anti-gun zealots insist on adding a gun-control poison pill to an otherwise good bill is just another example of the shameful politics Americans hate.”

A week later, a new study based on FBI data revealed that intimate partner homicides in America have been steadily on the rise, increasing 19 percent between 2014 and 2017. In 2017, a total of 2,237 victims were killed. Two thirds of them were women, most of whom were shot to death.

Additional research by Olivia Exstrum