Jay Mallin/ZUMA

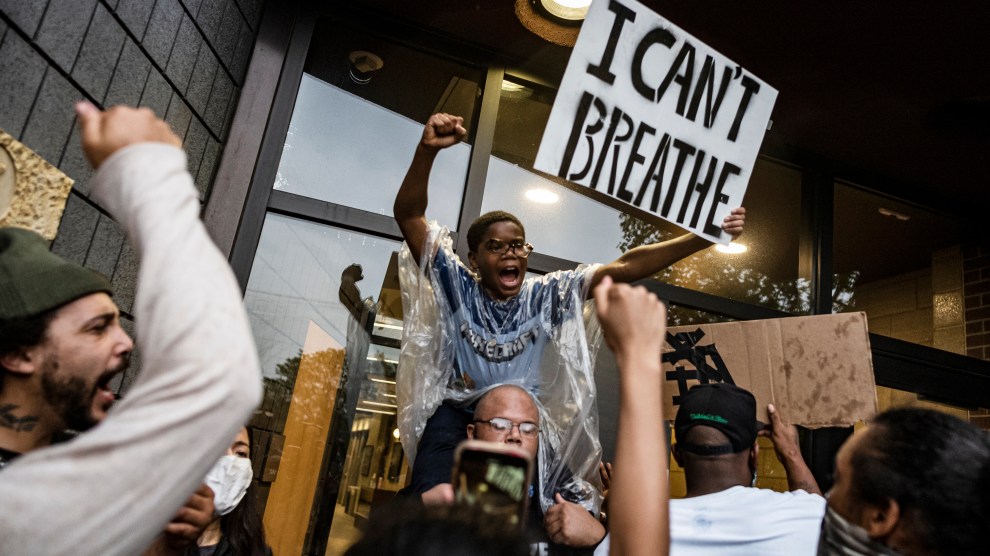

The civil unrest rocking the country in the wake of George Floyd’s death under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer has many catalysts. Among the more immediate is President Donald Trump and his first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, who freed local police departments from federal oversight and signaled that police brutality was no longer a problem that the federal government had an interest in solving. For police officers and departments with histories of terrorizing people rather than building relationships with communities they are supposed to protect, that message was heard loud and clear.

After the police officers who beat Rodney King in March 1991 in Los Angeles were acquitted, leading to the Los Angeles riots, Congress took action by giving the federal government oversight of local police departments. As Mother Jones reported in 2017, on the 25th anniversary of those riots:

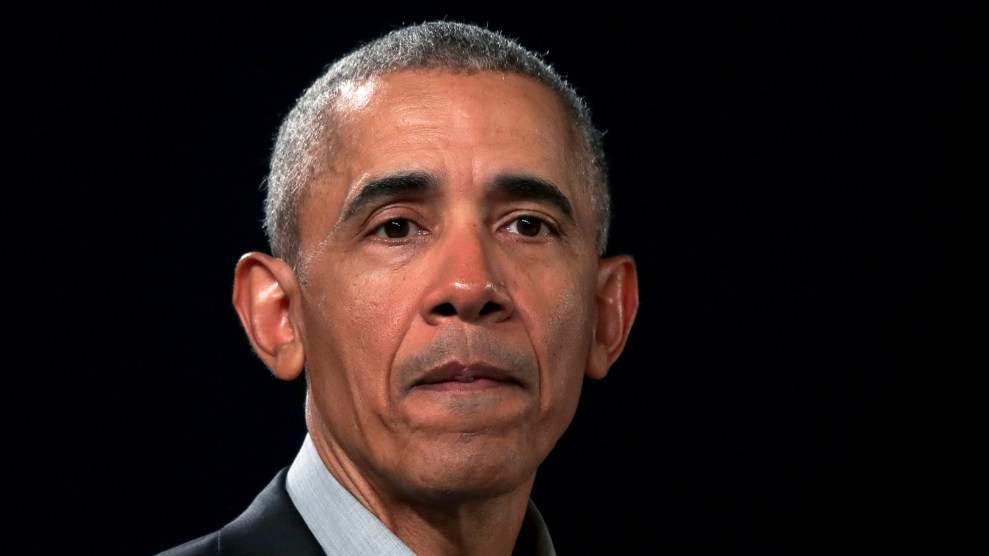

Since then, the Justice Department has launched 70 investigations into state and local law enforcement agencies and has negotiated 40 reform agreements, half of which are court-enforced consent decrees. The Obama administration was particularly active with this policy, enforcing 14 consent decrees for troubled police agencies, from Ferguson, Missouri, to Baltimore.

The riots’ 25th anniversary also happened to mark the beginning of the Trump administration. Jeff Sessions, newly installed as attorney general, immediately set out to undo years of progress on police and criminal justice reform. In April of 2017, a federal judge approved a consent decree—a legally-binding agreement between the Justice Department and a police department mandating reforms that is enforced by a federal judge—in Baltimore, finding that Sessions’ objections to an agreement made under the Obama administration came too late. “I have grave concerns that some provisions of this decree will reduce the lawful powers of the police department and result in a less safe city,” Sessions said at the time. “Make no mistake, Baltimore is facing a violent crime crisis.”

Though stymied from preventing Baltimore’s consent decree from going into effect, that same week he had ordered an internal review of all existing consent decrees nationwide. Even as Sessions’ relationship with the president turned sour over his recusal from the investigation into Russian election interference, the attorney general kept his head down and pulled back on criminal justice reforms, returning to a tough-on-crime policies that Sessions, a former prosecutor in Alabama, felt should never have ended. (Sessions is running for his old Senate seat in Alabama, but without the support of Trump he is not expected to win the Republican nomination in a July runoff.) The government’s police reform work came to a halt, while criminal justice policies reverted to harsher iterations.

When Trump finally fired Sessions in November 2018, the outgoing attorney general had one final trick up his sleeve. Before leaving the Justice Department, he quietly signed a memorandum in one of his last official acts all but ending the department’s oversight of police departments. The memorandum made the Trump administration’s de facto policy against new consent decrees official, while extending the same hands-off policy to other areas of federal enforcement involving state responsibilities in areas like pollution and voting rights. Experts predicted that even departments already under current federal oversight might once again act with impunity because the memo undercut the authority of civil rights attorneys to enforce them. Sessions’ memo set policy, but it also sent a message to police departments that they would no longer have to answer to the federal government—not even when when officer shootings draw national attention.

This message was sent not just in the order to pare back enforcement, but in the states’ rights language framing the 7-page document that has historically signaled support for state repression over the rights of black people. “Sessions’ memo also takes pains to emphasize that states are ‘sovereign’ with ‘special and protected roles’ and that, when investigating them, the Justice Department must afford states the ‘respect and comity deserving of a separate sovereign,'” Christy Lopez, who oversaw investigations by the department into local police agencies during the Obama administration, wrote at the time the memo was issued. “In his view, the Justice Department should be more concerned about protecting states from the burden of abiding by federal law than about protecting individuals from being hurt or killed by the state.”

Lopez then made a prescient prediction: “As has so often been the case with this administration, we will have to look to the courts, to local governments and to grass-roots political protest and pressure to protect our civil rights from police abuse. Because, as the Sessions memo confirms, this Justice Department has no intention of letting its civil rights division protect us from abuse by the state.”

Officer Derek Chauvin calmly kneeled on George Floyd’s neck until his body went limp after nearly four years of an administration that turned its back on police reforms and gave cops the green light to use excessive force. His actions showed the country the impunity some police officers still feel in 2020 to mistreat and even murder black people. That remains obvious in how some officers across the country have responded to the protests with unlawful action and more excessive force, all as the cell phone cameras are rolling. Perhaps they took comfort in what the current attorney general, William Barr said in a speech just a few months ago: “if communities don’t give [police] support and respect, they might find themselves without the police protection they need.”

The security forces in Minneapolis this weekend who ordered people to move from their porches into their houses and shot paint canisters at those who lingered may have felt protected by the friendship between Trump and the head of their police union, Bob Kroll, an officer with a long disciplinary record and history of discrimination who nevertheless rose to be the union’s president. When Trump traveled to Minnesota for a rally last October, Kroll took the stage in a “Cops for Trump” t-shirt and praised the president for liberating his officers from the constraints placed on them by the previous administration. “The Obama administration and the handcuffing and oppression of police was despicable,” he said. “The first thing President Trump did when he took office was turn that around, got rid of the Holder-Loretta Lynch regime and decided to start letting the cops do their job, put the handcuffs on the criminals instead of us.”

Uncovered: Last October, the head of the Minneapolis police union — which days ago warned against a “rush to judgment” of the officers involved in George Floyd’s death — spoke at a Trump rally and praised him for ending the “handcuffing and oppression” of police under Obama. pic.twitter.com/oW1olwWZh5

— The Recount (@therecount) May 30, 2020

No one knows if actions by Trump and Sessions led to George Floyd’s death or not. But neither his death nor the widespread unrest began in a vacuum. Trump, who often says the quiet part loud, has urged police to use excessive force in tweets from the White House. On Monday, Trump told governors on a call that “you have to dominate” protesters. If police were listening, they once again heard that the administration would do nothing to discourage their worst behavior.