Students walk out of school to demand justice for Amir Locke at Central High School in Saint Paul, Minnesota. DeeCee Carter/MediaPunch /IPX via AP

Amir Locke, a 22-year-old aspiring musician, was sleeping on a couch in his cousin’s Minneapolis home on a Wednesday morning this month when SWAT officers entered without knocking. “Get on the ground! Get on the fucking ground!” one of the cops shouted.

As Locke began to move, a pistol in his hand, the officers opened fire. Locke, who was not a subject of the police’s investigation or named in their warrant, was shot dead before he could even figure out what was going on.

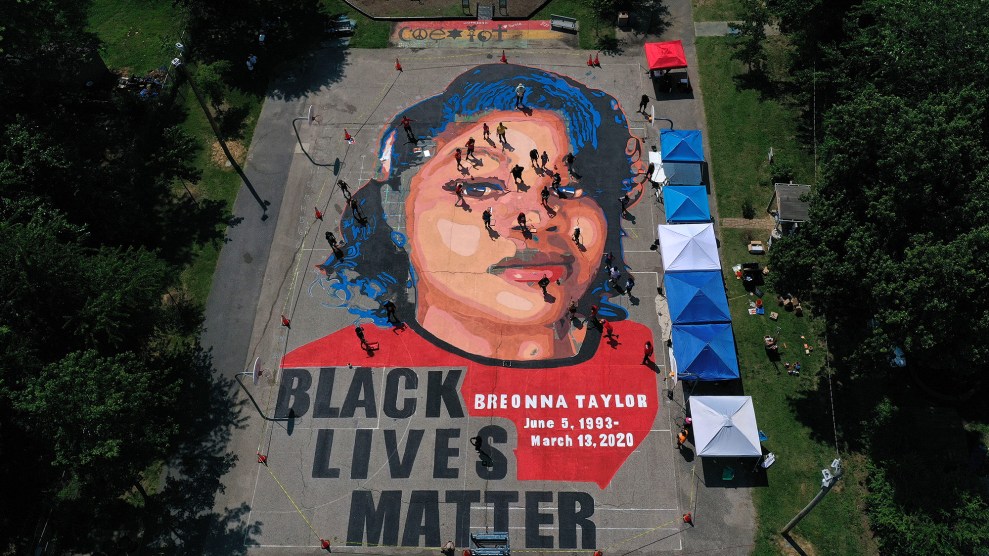

The case triggered fresh protests and renewed calls to ban warrants that allow cops to enter homes without knocking. “Like the case of Breonna Taylor, the tragic killing of Amir Locke shows a pattern of no-knock warrants having deadly consequences for Black Americans,” attorney Ben Crump, representing Locke’s family, told NPR. As I reported previously, Taylor, a 26-year-old EMT who died in a raid in Kentucky in 2020, was just one of a shocking number of Black people to be killed under similar circumstances. “This is yet another example of why we need to put an end to these kinds of search warrants,” said Crump, “so that one day, Black Americans will be able to sleep safely in their beds at night.”

Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey responded to Locke’s killing this week by placing a temporary moratorium on no-knock warrants, except for in some dangerous scenarios like hostage situations. (He previously tried to reform the use of these warrants in 2020.)

But even if the mayor were to fully ban no-knock warrants, as Locke’s family requested, it wouldn’t stop police from killing people during raids, argues data analyst Samuel Sinyangwe, who founded the Police Scorecard, which tracks police violence. He thinks the whole mentality behind police raids needs an overhaul. Many more people die unnecessarily in regular knock-and-announce raids than they do in no-knock raids. That’s partly because departments often don’t dictate how long officers must wait after knocking, or their policies include exceptions that let police rush in fast to maintain the element of surprise. “The police knock and wait and then kill somebody anyway,” Sinyangwe explains, “so just creating a delay is not ultimately a big game-changer.”

So how should Minneapolis and other cities stop these unnecessary killings? “Part of this is to think about, zooming out, how do we save the largest number of lives?” says Sinyangwe. “How do we make the biggest impact in terms of reducing police violence?” I called him up to hear more.

What makes no-knock warrants especially dangerous?

Well, obviously they provide less time or no time at all for the civilian who’s having their home invaded. People are often asleep, as we saw in the case of Amir Locke, and startled and not sure what’s going on. And meanwhile, police interpret that surprise as a threat and use that as a pretext to kill people. Often there are flashbangs. There are a whole host of people in the vicinity who are traumatized.

How common are these raids?

Nobody knows, but there are various figures that are used as back-of-the napkin estimates: More than a decade ago, there was a survey of police and sheriff’s departments across the country, and based on that survey, the researcher estimated there were between 20,000 and 60,000 no-knock [and quick-knock] raids a year. But today there’s no national database on this, as is the case with other forms of police violence. So nobody really knows. It’s likely in the tens of thousands.

What we do track are cases in which people are killed in police raids, and the type of raids in which they’re killed. We know there are at least 106 people who’ve been killed in police raids since 2013. And 34 percent of them were Black.

Of all those killings, only 31 were through no-knock warrants. [In the other cases, the cops had warrants that required them to knock.] Any type of police raid is harmful, whether or not the police knock, announce themselves, and wait a few seconds. At the end of the day, we’re talking about the police forcibly entering people’s homes, guns drawn. And in the majority of these cases, it’s over drugs. None of that is necessary.

Do police often justify themselves by saying, ‘We’re looking for drugs, and if we knock and announce ourselves, they might hide the drugs?”

Yeah, that’s one of the rationales. This is a product of the drug war, and we should be moving past that. And certainly, drugs ought not to be criminalized in my opinion, but certainly the police should not be able to forcibly enter people’s homes at threat of deadly force in order to find drugs. That’s not consistent with public safety.

There are jurisdictions that are moving away from this type of approach. I would suspect that many jurisdictions throughout Oregon are no longer getting search warrants and conducting raids for drug possession, given the drug decriminalization in the state.

How are other places restricting these raids? It seems like the focus is mostly on banning no-knocks.

Yeah. An increasing number of cities and even states have passed legislation generally targeting no-knock warrants, and in most cases restricting the use of no-knock warrants to situations in which there’s supposedly a violent crime or an imminent threat. Minneapolis is one of those jurisdictions. [In 2020 the city restricted how officers used these warrants, requiring them to announce their presence; Frey incorrectly described the policy as a ban during his reelection campaign last year.] Nevertheless, the loopholes in those laws and policies are often what the police cite to continue doing raids: In Minneapolis, they continued to do over 90 raids after the policy was passed, and three raids on the night Locke was murdered. Locke was not a threat to anyone—he was asleep. So, the efforts happening right now in cities and states across the country are often insufficient.

I will say that there are some jurisdictions that have reduced the use of no-knock warrants. Milwaukee substantially reduced the number of no-knock warrants over the past few years. One of the things that did happen there in 2019, right before we saw this precipitous decline, was that an officer was killed while conducting a raid. So it might be that the police decided it wasn’t safe for them to do the raids and then suddenly the numbers declined.

That’s interesting. It makes sense that no-knock raids would be dangerous for police, since people who are awoken suddenly without warning might think they’re being attacked by a burglar and might be more likely to fire on the police.

Yeah, and there are cases in which that happens. There are police who’ve been killed. There are even more civilians who’ve been killed.

With regular warrants, like knock-and-announce warrants, how much time do officers have to give between knocking and running inside?

It depends on the policy. But ultimately, we’re losing the forest for the trees: There are certain policies that recommend 30 seconds, and the police wait 30 seconds before entering the house. But again, when we look at the data, there are more people killed by police in knock-and-announce raids than in no-knock raids. The police knock and wait and then kill somebody anyway. So just creating a delay is not ultimately a big game-changer.

In Breonna Taylor’s case, the police claimed they knocked and announced themselves, but even so, nobody heard them and Taylor was killed.

Yeah. The police are going to continue handling these cases in the way they always have.

You’ve mentioned that ideally, the goal would be to prevent police from ever entering people’s homes without their permission. Are there smaller reforms that would be helpful beyond just banning no-knock raids? Like requiring raids to happen only during daylight, so that people can be awake and less startled?

I mean, sure, that could help along the margins. There are the technical things: Who signs off on the warrant? And what time does the raid happen? And how many seconds do the officers wait? What do they have to report afterward? And do they capture it on video?

But ultimately, this isn’t a situation where we can just fix these small technical issues and expect a completely different outcome. Because when we look at the data, the police are continuing to kill people even when they knock and announce. They’re continuing to kill people even during the day. They’re continuing to kill people and then not disclose the information about the circumstances or whatever imminent threat they alleged was perceived, whether or not there was video. So those technical fixes might make a difference on the margins. But I don’t think they will fundamentally change the dynamic.

We should think about this as one of many issues that needs to be addressed in policing: There were at least 106 people killed in raids of any type since 2013, but in that time period, there were about 10,000 people killed by police total. So, this is about 1 percent of the total number of people killed by the police. We have to think of this as a broader system and not continually respond to the particular circumstances of each incident. We saw after George Floyd was murdered, there was a big push around banning chokeholds. And now we’re seeing with Amir Locke, there’s a big push around no-knock warrants. But ultimately, we could stop chokeholds, we could stop no-knock raids tomorrow, and approximately 99 percent of the same number of people will be killed by police next year. So we have to think more expansively about how do we actually save lives, the largest number of lives, and make the biggest impact in this moment? Because otherwise, we’ll be right back here again.