Illustration: John Hendrix

On a warm, sticky winter morning, I waited nervously in a parking lot in Foshan, a city in southeastern China’s smog-choked Pearl River delta, for a man I’d never met. His name was Mr. Ou, and he ran the sprawling factory in front of me, a jumble of offices, low-slung buildings, and warehouses. Though the factory was teeming with workers, a Subaru SUV and BMW coupe were the only cars in the lot. Drab, gray worker dormitories loomed nearby, and between them ran a dusty road that led to the factory. At last a young man emerged from an office building. He motioned for me to follow him in.

I settled onto a plush leather couch and absorbed the decor. Framed awards and certificates covered the walls. A shopping-cart-size wooden frog stood sentry in the center of the room. Ping golf clubs leaned against one wall; a Rolling Stones commemorative electric guitar gathered dust behind a chair. And there were grills: a small kettle grill on a desk, a brushed-steel gas grill on the far side of the room, grills stacked atop other grills. This was Mr. Ou’s trade: supplying Western retailers with the cooking apparatus of patio parties and Fourth of July bashes.

The young man closed the door. He took the chair to my right, lit a cigarette, and met my stare as if to say, Let’s get on with it. Only then did I realize I was not talking to an assistant.

Mr. Ou had the good looks of a judge on one of those breathless Chinese talent shows. He wore a tailored blazer, an expensive-looking watch, polished leather shoes, and colorful striped socks. He asked why I’d come to China, why I cared about his factory. An American consultant, I said, had suggested I tour his operation, Foshan Juniu Metal Manufacturing, because Mr. Ou was part of a hallmark sustainability program launched by the company I had come to China to investigate—Walmart.

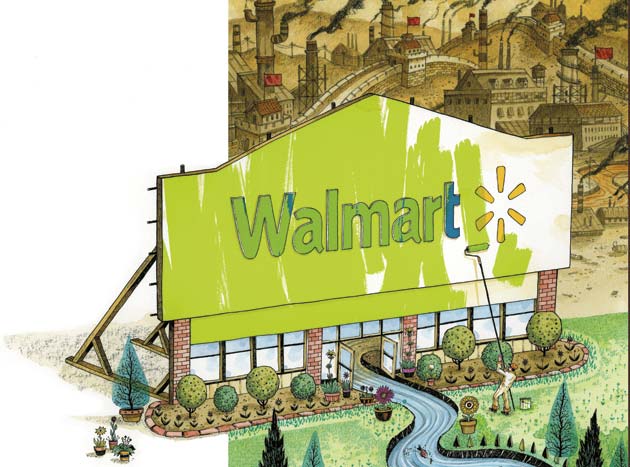

In October 2005, Walmart announced plans to transform itself into one of the greenest corporations in the world. Then-CEO Lee Scott called sustainability “essential to our future success as a retailer.” The company has been especially vocal about shrinking its environmental footprint in China, its manufacturing hub. But do the facts on the ground match Walmart’s rhetoric? This was the question that had brought me to Mr. Ou.

Mr. Ou dragged on his cigarette, mulling my questions. “Okay,” he finally said. “I will tell you what you want to know.”

He was 33 years old and came from a manufacturing family. His parents ran a factory making packaging for barbecue grills and then, in 1994, began producing the grills themselves. By 2004, when Mr. Ou took over from his parents, Walmart was a major customer. In 2008, Mr. Ou signed his operation up as one of 200 plants whose energy efficiency Walmart would seek to increase by 20 percent.

Mr. Ou said all this in a smoky rattle of a voice, but he perked up when he talked about this program. “As the biggest retailer in the world,” he told me, “Walmart has a responsibility to do this.” For the energy efficiency program, he submitted monthly reports to Walmart and met with a Walmart consultant about energy-saving equipment. But he had his doubts. While Walmart executives preached sustainability, its buyers pushed him to lower prices by 3 or 5 percent each year. Operating on the thinnest of margins and scrambling to keep up with Walmart’s demands, he said, factories just don’t have the time or capital to invest in green projects. “They will work the suppliers to death,” he told me.

Mr. Ou said all this in a smoky rattle of a voice, but he perked up when he talked about this program. “As the biggest retailer in the world,” he told me, “Walmart has a responsibility to do this.” For the energy efficiency program, he submitted monthly reports to Walmart and met with a Walmart consultant about energy-saving equipment. But he had his doubts. While Walmart executives preached sustainability, its buyers pushed him to lower prices by 3 or 5 percent each year. Operating on the thinnest of margins and scrambling to keep up with Walmart’s demands, he said, factories just don’t have the time or capital to invest in green projects. “They will work the suppliers to death,” he told me.

After our meeting, Mr. Ou’s assistant, who looked slightly older than Mr. Ou, took me around the factory grounds, 25 acres in all. One- and two-story buildings lined the road, and a bilious-looking river cut through the property. When I asked, the assistant said its pollution came from other factories. We passed through a dark, ear-splittingly loud packaging facility where, amid stacks of Styrofoam blocks and plastic-wrapped metal parts, workers eyed us warily before turning back to the production line. Kingsford grill boxes reached high toward the ceiling, WAL-MART printed on the side.

Near the end of the tour, the assistant led me inside a hangarlike plant filled with the whine of heavy machinery. Workers in jeans and T-shirts operated heavy presses, stamping metal sheets into grill lids. We sidled up to an unoccupied machine. Bits of metal glittered at its base like coins in a fountain. The assistant motioned for me to look closer, then pointed to a shoebox-size metal box affixed to one side that read “Mascot.” When turned on, he proudly explained, this box slashed electricity usage. I had asked to see the factory’s energy efficiency investments, and this was it.

Soon after, the assistant led me back to the parking lot. The tour was over. Mr. Ou gave me his card and told me to stay in touch.

It was never made clear to me how those energy-saving boxes exactly worked. What I did know was that Mr. Ou had welcomed me into his factory, served me tea, answered my questions, and let me snoop around. He seemed like a forward-thinking businessman with a strong belief in sustainability—exactly the right type to carry forward Walmart’s vision for a leaner, greener supply chain in a country smothered by pollution.

Except, as far as Mr. Ou was concerned, that vision never came to life. And no one, he later told me, ever explained why.

Walmart’s campaign to green everything from its break rooms to its global supply chain is one of the most publicized, and controversial, experiments in American retail. The company had made a halfhearted attempt in the ’80s and ’90s, with a few green products and ecofriendly stores. But this latest effort was different. It was sweeping, embracing every part of the company’s business. It emanated directly from the CEO’s office. And, perhaps most remarkably, some of Walmart’s erstwhile critics in the environmental movement—the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), and World Wildlife Fund, among others—got on board. Former Sierra Club president Adam Werbach was hired to spread the green message among Walmart’s 1.4 million US employees.

Almost seven years into the program, many environmentalists remain convinced that Walmart is serious about sustainability—and that its actions can have a major impact on the world economy because of the gravitational pull of its vast network of suppliers, customers, and employees. Walmart’s environmental initiatives in China have been heralded—most recently by Orville Schell in The Atlantic—as a key force in spurring other corporations to embrace sound environmental practices. My reporting—more than a year of research that took me from Arkansas to China—suggests a more complex, less flattering story: Walmart has made laudable though modest progress on many of its goals. But with the global economic slowdown tugging at the company’s profit margins, people involved with the environmental campaign say the momentum seems to be stalling or vanishing entirely.

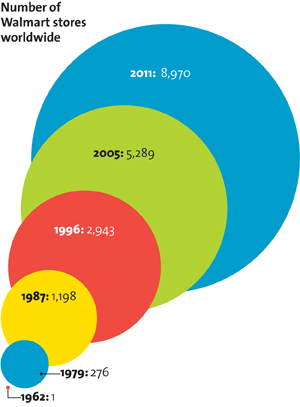

Since launching its sustainability program, Walmart has pledged to eliminate waste, use only renewable energy, sell more organic produce, support small farmers, and slash its energy footprint. That’s no easy task: Each second, 330 people buy something from one of Walmart’s 8,970 stores worldwide. With 2.1 million workers, it is the world’s largest private employer. Its carbon footprint—from its stores, distribution centers, company offices, corporate jets, and so on—totaled 21.4 million metric tons in 2010, more than that of half the world’s countries, according to data Walmart provided to the Carbon Disclosure Project.

Since launching its sustainability program, Walmart has pledged to eliminate waste, use only renewable energy, sell more organic produce, support small farmers, and slash its energy footprint. That’s no easy task: Each second, 330 people buy something from one of Walmart’s 8,970 stores worldwide. With 2.1 million workers, it is the world’s largest private employer. Its carbon footprint—from its stores, distribution centers, company offices, corporate jets, and so on—totaled 21.4 million metric tons in 2010, more than that of half the world’s countries, according to data Walmart provided to the Carbon Disclosure Project.

But that figure doesn’t include Walmart’s supply chain, a web of more than 100,000 suppliers from Tennessee to Turkey, Cambodia to Mexico. These companies fall largely into two categories: Some make house-brand products to Walmart specifications: Great Value (food), George (clothing), Mainstays (furniture). Then there are name-brand products, like Del Monte pineapples, Coleman tents, and Bic pens. Sometimes, a brand will make a Walmart-specific product; General Electric, for instance, sells kitchen appliances exclusive to Walmart and is subject to Walmart’s factory regulations. But neither the house-brand nor name-brand suppliers necessarily produce the jeans, tents, or toothbrushes they sell to Walmart. That work is done by contractors and subcontractors, which include many unregulated “shadow” factories—and that’s where some of the most carbon-heavy, polluting parts of the manufacturing process happen.

Counting all the suppliers, factories, mills, farms, and so on in its supply chain, Walmart estimates its total carbon footprint is closer to at least 200 million metric tons. And even that estimate doesn’t include all of the companies Walmart does business with, such as its distribution trucking firms.

In the past, Walmart’s outsize carbon footprint had made the company a favorite target of environmentalists. But in 2009, as hope for a congressional cap-and-trade deal evaporated and the Copenhagen climate talks ended in a stalemate, they began to see Walmart in a different light: If they could make the world’s largest retailer greener, other businesses might follow suit. EDF had opened its own office near Walmart headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas, embedding its employees in the “belly of the beast,” as one staffer put it. “Even though they’re a party of last resort, they’re our only hope at the moment,” said Linda Greer, an NRDC scientist who works with Walmart. “They have the potential to change the world.”

Key word: potential. So far the company has made strides on only some of its goals. It says it has boosted its truck fleet’s efficiency by 60 percent, eliminated hazardous materials from most electronics it sells, cut plastic bag use by more than 20 percent since 2007, and sold 466 million compact fluorescent lightbulbs in four years.

But interviews with key insiders and the company’s own reports reveal that on some of its biggest promises, Walmart’s results are underwhelming:

At a glitzy Beijing confab in 2008, Walmart pledged to make Chinese suppliers agree to comply with labor and environmental laws and standards starting in January 2009. (All other suppliers were to comply by 2011.) As of its 2011 Global Responsibility Report, Walmart had no updates except to say that the compliance agreement “is being strengthened.”

At a glitzy Beijing confab in 2008, Walmart pledged to make Chinese suppliers agree to comply with labor and environmental laws and standards starting in January 2009. (All other suppliers were to comply by 2011.) As of its 2011 Global Responsibility Report, Walmart had no updates except to say that the compliance agreement “is being strengthened.”

Walmart committed to eliminate 25 percent of solid waste from its US stores by October 2008. In its 2011 responsibility report, Walmart said it had no data for 2005, 2006, and 2007. Instead, it touted a “waste-redirection” rate of 64 percent in the 2010 fiscal year.

In 2008, Walmart pledged to boost energy efficiency by 20 percent per unit produced at 200 Chinese factories, including Mr. Ou’s, by this year. In April 2011, it announced 119 factories had hit the target. Yet later that month, EDF, a crucial partner in China, left the program over Walmart’s lack of cooperation, several sources told me. By year’s end, the program was dormant.

Walmart’s goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20 percent at its stores and distribution centers worldwide by 2012 was half met by the time of the 2011 responsibility report.

And even where Walmart has made its goals, questions linger. The retailer says every supplier making private-label and non-name-brand goods has provided the name and location of every factory involved in making those products. Yet Walmart concedes that the use of murky subcontractors is widespread in China, Africa, the Middle East, and Bangladesh. Walmart also won’t provide details about how it achieved its goal, whether suppliers were asked or compelled to share factory information, and whether any suppliers lost orders or were fired for unsatisfactory responses. My repeated attempts to get Walmart to answer specific questions yielded little in the way of hard data but plenty of PR speak. “We believe the sheer volume and ambition of our goals—and our annually reported progress—speak for themselves,” a spokeswoman wrote me in one typical exchange.

That’s why I decided to go see for myself.

Walmart began buying Chinese-made goods in 1993. The country’s first supercenter opened three years later in Shenzhen. Today, the company directly employs 96,800 people in China and operates 357 Chinese stores. Walmart’s supply chain includes some 30,000 Chinese factories, which produce an estimated 70 percent of all of the goods it sells. Walmart’s global sourcing headquarters, the nerve center for its international operations, is also located in Shenzhen, a booming city on the southeastern coast.

In December 2010 I arrived in Foshan, a city in the heart of Guangdong province. Known as the “workshop of the world” and bordering Hong Kong, Guangdong is packed with factories that churn out Barbies and bras, tube socks and toilet brushes, iPhones and plasma TVs. The province’s gross domestic product in 2010 was $690 billion, more than the GDP of Argentina, Saudi Arabia, or South Africa.

In December 2010 I arrived in Foshan, a city in the heart of Guangdong province. Known as the “workshop of the world” and bordering Hong Kong, Guangdong is packed with factories that churn out Barbies and bras, tube socks and toilet brushes, iPhones and plasma TVs. The province’s gross domestic product in 2010 was $690 billion, more than the GDP of Argentina, Saudi Arabia, or South Africa.

Walmart has connected other journalists with its suppliers and corporate officials in China in the past two years, but it had declined a half-dozen requests from me. And locating these sources on my own proved no easy task. The company closely guards all information about who makes its products. Aside from Mr. Ou, almost everyone connected to Walmart I met in China insisted I not use their real names for fear of being blackballed by Walmart and other employers.

Which is why I’ll call the former Walmart factory auditor I met one Saturday night Michael Chao. Chao was in his mid-30s and spoke good English. We couldn’t talk in public, he said, so we relocated to a friend’s office a few blocks away.

Chao joined Walmart as an auditor in 2004 after two years at an independent auditing firm. He spent four years at Walmart, which, combined with his previous gig, was plenty long enough to understand how auditing in China really works.

Walmart helped spawn the supplier auditing industry. After a scathing NBC Dateline report in 1992 uncovered child labor at a Walmart supplier in Bangladesh, the company denied the allegations but then created a supplier code of conduct that, among other things, outlawed child and prison labor. Other big-name companies followed suit, and soon there was a market for companies that could police those firms. Today, Walmart’s auditors inspect factories, meet with managers, scrutinize wage records, and interview individual workers to look for labor, health, and safety violations.

They have recently tried to keep an eye out for environmental issues as well, but it hasn’t been easy, since the inspectors are already overtaxed. Auditing is a demanding job, Chao told me. Burnout is common. Factories often cook their books, keeping two sets of records—the real ones, and a clean version for the auditors. Managers coach employees to lie. And a passel of companies help suppliers fudge their numbers and pass compliance audits.

Sometimes the auditors themselves are corrupt, Chao said, willing to overlook violations in exchange for a hongbao—a bribe. (Hongbao means “red envelope,” usually a bill-shaped sleeve filled with cash given as a gift at family celebrations.) Walmart, which has publicly acknowledged firing auditors for taking bribes, says it investigates all reports of corruption. But Chao told me that they can’t catch all the crooked auditors.

Walmart hired a crop of young college graduates to replace auditors who were inured to corruption, but challenges remained. Like off-the-books subcontracting. In China, auditors typically see only “five-star” factories, so named for China’s rating system for hotels and restaurants. These companies, he explained, obey the law, treat their workers fairly, pay decent wages, and ensure safe working conditions, by local standards. But Walmart and others often demand more than their five-star suppliers can produce, so a company scrambling to fill a massive order for, say, action figures will outsource to a shadow factory.

Walmart hired a crop of young college graduates to replace auditors who were inured to corruption, but challenges remained. Like off-the-books subcontracting. In China, auditors typically see only “five-star” factories, so named for China’s rating system for hotels and restaurants. These companies, he explained, obey the law, treat their workers fairly, pay decent wages, and ensure safe working conditions, by local standards. But Walmart and others often demand more than their five-star suppliers can produce, so a company scrambling to fill a massive order for, say, action figures will outsource to a shadow factory.

A shadow factory can be a mom-and-pop operation in someone’s house, or it can be a full-fledged factory hidden on the same property as a five-star. Regulations don’t apply inside a shadow factory, Chao said. Consultants and experts who’ve worked in China for decades say there are tens of thousands of shadow factories, and that up to 70 or even 80 percent of five-stars will outsource more than half of a given production order to shadow factories. At Walmart, Chao said, “We would look in the system which shows the [five-star] factory has only 300 people to handle an operation receiving massive production orders worth millions of dollars. How does it add up?”

Good auditors aren’t blind to this, he noted. But they don’t have time to hunt down all the shadow factories, and they feel pressure not to cause trouble or stop orders from being filled.

Chao recalled one case at Walmart when his boss received a confidential tip about a toy supplier outsourcing production to a strange location. Chao and a colleague staked out the supplier. When a truck emerged, they jumped into a waiting taxi and tailed it until the truck pulled into a prison. Upon further investigation, Chao confirmed that the factory was using inmate labor and got Walmart to pull its orders from the supplier.

He told me that story not to trumpet his or Walmart’s detective skills—he said the auditors likely missed many more shadow factories than they caught—but to stress the slippery nature of the supply chain. Walmart’s American brass, Chao said, doesn’t have a complete enough understanding of Chinese manufacturing. “They have the basic concept, but the top management knows nothing about how to make it work” at the ground level, he said. “So they can say, ‘Oh, a sustainability program,’ but they can do nothing.”

Chao isn’t the only one to question Walmart’s auditing. In 2009, the advocacy group China Labor Watch obtained documents from a Walmart packaging supplier on how to hide or adjust safety and environmental records; how workers should lie to auditors about wages, benefits, and working hours; and how to conceal a shadow factory. Another investigation by the group uncovered forced overtime, phony pay stubs, poor living conditions, and the use of hazardous chemicals at a Walmart shoe factory. Walmart-hired auditors had previously raised no concerns with either plant.

Chao isn’t the only one to question Walmart’s auditing. In 2009, the advocacy group China Labor Watch obtained documents from a Walmart packaging supplier on how to hide or adjust safety and environmental records; how workers should lie to auditors about wages, benefits, and working hours; and how to conceal a shadow factory. Another investigation by the group uncovered forced overtime, phony pay stubs, poor living conditions, and the use of hazardous chemicals at a Walmart shoe factory. Walmart-hired auditors had previously raised no concerns with either plant.

Li Qiang, China Labor Watch’s executive director, told me that Walmart’s auditing process has been plagued with fraud for years. In 2007, Li, who says he’s met with Walmart officials numerous times, urged the retailer to scrap its corruption-riddled internal auditing program. Walmart followed his advice, but Li discovered that the problems hadn’t disappeared. In November 2011, a lawsuit filed by Li’s group against Intertek, an international third-party auditing company, describes how in December 2009 an Intertek auditor took a bribe from a Dongguan toy factory while overlooking “extensive fraud” in pay and hours records. (An Intertek spokeswoman said the suit “has no merit” but declined to comment on specific allegations.) In its 2011 Global Responsibility Report, Walmart briefly hinted at this problem: “Lack of complete transparency to production practices [in China] has hindered our ability to implement meaningful change at the factory level.”

Li said these problems were systemic. “If the fraud in the auditing system isn’t solved,” he told me, “I’m far from optimistic about Walmart’s environmental programs.”

Thirty years ago, Shenzhen was a drab fishing village on the South China Sea, a place so remote it didn’t have a single traffic light. Then, as part of his economic reforms, Communist Party leader Deng Xiaopeng named Shenzhen the country’s first “special economic zone,” with laissez-faire trade policies and favorable manufacturing laws put in place to lure foreign investment. Shenzhen’s economy exploded, its GDP climbing from $31 million in 1979 to $107.8 billion in 2007. Today Shenzhen is China’s third-largest port city, packed with skyscrapers, nightclubs, and fancy hotels. Among the most luxurious is the Shangri-La, where, on any given morning, buyers for American retailers mill around the marble-floored lobby waiting for rides to factories. I sat down in the bar one Friday and ordered a cappuccino that arrived with the letters “S-L” spelled in froth.

I was there to meet Terry Foecke (pronounced FAKE-ee), a consultant spearheading Walmart’s factory energy efficiency program in China. In a lobby full of Westerners, Foecke cut an unmistakable figure—thickly bearded, 6-foot-3, with a broad belly and hip square-framed glasses. He was an unlikely Walmart ally: a soft-spoken, almost professorial progressive who quoted George Bernard Shaw and told me he spoke out against runaway consumerism at his Unitarian church back home in Minnesota.

Foecke’s actual employer was the Environmental Defense Fund, which in 2008 partnered with Walmart on the campaign to make factories more energy efficient. That degree of separation gave him the freedom to talk openly about implementing one of the retailer’s most ambitious efforts: shrinking energy usage by 20 percent at 200 Chinese suppliers by 2012, the same program Mr. Ou had participated in. Foecke spent many days on the road, visiting factories and performing “rapid assessments”—two- or three-hour sweeps through a factory to pick out quick and easy ways to save energy and money. Foecke and his crack team of sleuths could find up to 60 percent in energy savings in a single visit, pulling down banks of lights that illuminated empty space or plugging leaky equipment.

Foecke wanted me to ride along on one of his assessments. But Walmart officials denied multiple requests to do so, and so I had to settle for Foecke’s colorful written accounts. Here he is walking through an aging factory that makes plastic Christmas trees and other fake flora:

“Then it was on to the plastic injection molders. Wow, I thought I had stumbled into Mr. Wizard’s Wayback Machine and somebody dialed in ‘1960.’ Wide-open hoppers (hard to keep the polymer dry that way; causes lot of rejects), leaking hydraulics bandaged up with rags; filthy motors everywhere, and more compressed air than I believe I have yet seen used. They have 50-60 smaller molders crammed into the space someone in [Minnesota] would use for a 3-car garage, all actuated with compressed air instead of hydraulics, making bark and twigs and stems and such, sometimes even co-molding a stem onto a previously-made flower. P admitted later that the place made him jumpy, certified safety engineer that he is. The lack of safety guards and [emergency fail-safe] switches and doors and just plain space WAS impressive in a how-do-they-do-it? way. I got speared in the belly by an actuator, but in my defense the darn thing traveled a good foot into the manway.”

But there were flaws with Foecke’s program. Walmart said the participants in it were “top” suppliers, suggesting they had been chosen for their size. In fact, most of the 200 participating factories were simply those whose forward-thinking owners, like Mr. Ou, had volunteered, Foecke said. (And, of course, none of the 200 were shadow factories.) Also, the data in Foecke’s program were self-reported. Foecke said he’d accepted Walmart’s “inspire, not require” philosophy at the outset. Once Walmart expanded the program, he hoped it’d make energy metering mandatory. Otherwise, he explained, “the factories can say whatever they want, and when you have self-reported data it’s built on sand. I said [to Walmart], ‘You can do this for a while, but eventually cut the crap.'”

But there were flaws with Foecke’s program. Walmart said the participants in it were “top” suppliers, suggesting they had been chosen for their size. In fact, most of the 200 participating factories were simply those whose forward-thinking owners, like Mr. Ou, had volunteered, Foecke said. (And, of course, none of the 200 were shadow factories.) Also, the data in Foecke’s program were self-reported. Foecke said he’d accepted Walmart’s “inspire, not require” philosophy at the outset. Once Walmart expanded the program, he hoped it’d make energy metering mandatory. Otherwise, he explained, “the factories can say whatever they want, and when you have self-reported data it’s built on sand. I said [to Walmart], ‘You can do this for a while, but eventually cut the crap.'”

Yet two years into the program, well past the point where Foecke had expected it to be expanded dramatically, it was still stuck in the pilot phase. He’d seen similar hesitance on environmental issues at other companies, and that had usually spelled doom for energy efficiency programs. “It happens all the time,” he said. “You go into big organizations, you get atomic decay, and unless there’s something else there that drags it to the next level and starts integrating it, it becomes the flavor of the month.”

A casual reader of the business pages could pinpoint the source of Walmart’s hesitation. From 2009 to 2011, Walmart suffered seven straight quarters of declining sales in its US stores, a historic slump blamed on anemic job growth, weak demand, and high gas prices. Walmart responded by unveiling “It’s Back,” a plan to reclaim its original, bargain-seeking customer base by restocking 8,500 down-home products it had axed in an effort to declutter its shelves and class up its image. It also revived the popular “Action Alley,” steeply discounted pallets of merchandise stacked up in the middle of the aisles. “It’s Back” left suppliers and environmental partners wondering if this doubling-down on its crusade to be the cheapest retailer around might come at the expense of sustainability.

One insider who watched this unfold was Michelle Mauthe Harvey, an expert and EDF staffer. In 2007, Harvey opened EDF’s office in Bentonville, the Ozark country town that is home to Walmart’s headquarters. Bentonville was the site of Sam Walton’s first store, a five-and-dime that opened in 1951. In the decades that followed, Walmart transformed the town into a thriving international business hub. At least 750 companies that do business with Walmart have offices in the area, from Procter & Gamble to Levi Strauss to DreamWorks. Cushy subdivisions ring the town, and both the median household income and average home value easily outpace the state average.

On a blisteringly hot summer day last June, I met Harvey over brisket and sweet tea at Whole Hog Café, a barbecue joint near the Walmart headquarters. Harvey is embedded inside Walmart, attending internal meetings and interacting with key players. She lauded Walmart for its ambitious goals but winced when I brought up “It’s Back” and what it meant for sustainability. She said this roll-back initiative led some suppliers to think Walmart was stalling on sustainability as it grappled with slumping sales. “What’s been concerning to us is the number of people who contact us and say, ‘Is Walmart still interested in sustainability?'” She added, “There are still those [inside Walmart] who fall into the annoyed camp, who aren’t entirely sure it’s really necessary.”

Consider Walmart’s buyers, Harvey said, the people who negotiate with suppliers and help decide what makes it onto Walmart’s shelves. If Walmart’s sustainability ideal was to become reality, it needed to become part of buyers’ day-to-day decision making, a criterion on which they were evaluated. For instance, would the buyers be encouraged to choose a T-shirt that costs a half cent more apiece because it used safer chemicals or was dyed at an environmentally friendly mill? When Walmart embraces that notion, Harvey said, “that’s when sustainability is really embedded.”

“Is it there yet?” I asked.

“Is it there yet?” I asked.

“It’s not there yet.”

After nearly a year of my asking for an interview with a company official in Bentonville about the sustainability program, Walmart finally put me in touch with Jim Stanway, a rumpled-looking Brit who worked in the energy sector before joining Walmart in the late ’90s to help trim its energy bills. We met in a small conference room at the Sam Walton Development Center, accompanied by a Walmart flack who took notes throughout the interview.

A man who admits he’s “morbidly attracted by complexity,” Stanway was Walmart’s point man in working with the Carbon Disclosure Project to calculate that Walmart’s carbon footprint was greater than that of many industrialized countries. Stanway is now leading the campaign to cut 20 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions from Walmart’s supply chain by 2015.

Stanway rattled off his success stories, including uniting the fractious dairy industry behind using low-carbon cattle feed and methane digesters and selling Hollywood on the virtues of slimmer DVD packaging. A little plastic here, some cardboard there, and you’re talking millions of dollars in savings. Not only did suppliers see their costs shrink, so did customers. “We want to show things where we can deliver customer value on price and quality, and lower costs for suppliers,” Stanway said.

I’d hoped to ask Stanway about China, but the flack, who insisted on vetting all interview questions days beforehand, ruled out those questions, routing them to Walmart China. Despite four more requests, I never heard back.

Linda Greer is a sharp-witted, veteran scientist and director of the public health program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. She spoke to me about a program she started in 2007 called “Clean by Design,” which has brought together companies like Walmart, Gap, Nike, and H&M to develop a set of best practices for Chinese dye and finishing mills, one of the most energy-intensive sectors in the apparel industry.

Greer told me in 2010 that she’d turned to Walmart and other private companies for lack of other options. “We really couldn’t count on the Chinese environmental department to even come close to catching up on this in my lifetime,” she said. “The private sector stands alone, being the only functioning additional party over there.” She was no Walmart cheerleader but believed the company was making a sincere effort. “They’ve made a lot of ambitious promises, many of which were maybe naive in terms of how hard they are to implement.”

But when I checked in with her again last fall, her guarded optimism had given way to discouragement. She and her team had spent a year and a half assembling 10 best practices to reduce water, chemical, and energy use at the mills; their suggested repairs and upgrades paid for themselves in eight months’ time and, in some cases, saved energy use by 25 to 30 percent. The next step was putting the guidelines into practice, showcasing their benefits to lure other mills into the program. She asked the corporate partners for the names of four or five mills. Nike, Gap, and the others came through. Walmart gave her only one viable factory.

Greer was bitterly disappointed. “They’re not even up at the plate swinging at those balls,” she told me. (Walmart says it “continues to believe in—and promote” Greer’s program but gave no specifics as to how.)

An energy efficiency consultant who also works with Walmart (and requested anonymity; I’ll call him Martin) echoed those observations. He said there was overwhelming support for Walmart to succeed in China, given the ripple effect that would have in Chinese commerce. Yet 2011, he told me, was widely seen as a disappointing year. “The word on the street in China is: ‘Where is Walmart?'” he said. “Because we haven’t seen them continue to move forward in 2011.”

An energy efficiency consultant who also works with Walmart (and requested anonymity; I’ll call him Martin) echoed those observations. He said there was overwhelming support for Walmart to succeed in China, given the ripple effect that would have in Chinese commerce. Yet 2011, he told me, was widely seen as a disappointing year. “The word on the street in China is: ‘Where is Walmart?'” he said. “Because we haven’t seen them continue to move forward in 2011.”

Martin brought up a major Walmart supplier, a network of factories making name-brand products. (He asked that I not reveal the brand, but it’s a household name.) Like Mr. Ou once did, this supplier submitted scorecards on energy and water use to Walmart. The retailer’s response: silence. Martin said the supplier admitted to him that the data was “total crap,” but it never heard from Walmart one way or another. Martin summed up the supplier’s attitude toward Walmart scorecards like this: “Walmart sets a new target, everybody gets all excited, runs around for six months, and then everything kind of slows down and the wheels fall off.”

Eight months after my first conversation with Terry Foecke, I caught up with him again in Minnesota. Seeing little appetite from Walmart to expand the factory efficiency program, he’d ditched it to start his own energy consulting business. Foecke sounded more befuddled than bitter—he’d always seen Walmart’s factory project as a small but important first step. “It was key that they expand the program—that’s what we put on the table” in the beginning, he said. “Until they’re willing to do that, it’s not quite greenwashing, but it’s very close.”

Mr. Ou witnessed the demise of Foecke’s program firsthand. When I reconnected with him last winter, he said Walmart had stopped asking him for reports on Juniu’s energy usage. No one told him why. As far as he could tell, Walmart had canceled the program. Mr. Ou said he’d not lost his appetite for energy efficiency but admitted it was more difficult to make progress without Walmart’s pressure and expertise. “I spent a lot of time and energy,” he said. “It really is a pity that Walmart stopped the program.” (Walmart says it’s still finishing the pilot phase of the program.)

If there is any silver lining to Walmart’s wavering on sustainability in China, it’s that other major retailers have made significant progress. Foecke’s current clients include IKEA and Levi’s, companies that he said took a different approach to suppliers, building more durable relationships. It wasn’t a perfect model—IKEA has issues with shadow factories, too—but he was allowed to walk into factories, suggest changes, and speed up the sustainability process.

Foecke still credits Walmart for nudging other companies, and he told me he would work with them again. But he remained somewhat discouraged by what he’d seen. “I really do think they’re very distracted by the weakening economy, and they don’t want to spend any money on anything right now,” he told me.

The NRDC’s Greer said Walmart’s partners had every right to be critical of the company. “I would say we, the environmental community, have been enormously patient…We’ve not only been patiently waiting, we’ve been actively helping.” She went on, “At this point, we don’t see that they’re trying.” When Walmart fell short on her Chinese mill program as part of its goal to cut 20 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions from its supply chain, she says, “I thought, ‘There they go again.’ It breeds cynicism. Is this just a PR effort, or is this something they’re serious about?”