The River Rouge plant on the banks of the Detroit River emits enough pollution to cause 44 deaths each year. Photographs by Daniel Shea. See <a href="http://motherjones.com/blue-marble/2012/03/coal-photos">more photos</a> of the River Rouge plant.

By most accounts, the summer of 2010—when climate legislation died its slow, agonizing death on Capitol Hill—was not a happy time for environmentalists. So why was Mary Anne Hitt feeling buoyant, even hopeful? Part of the reason, no doubt, were the endorphins of first-time parenthood. Baby Hazel, born in April 2010, was fair like her mother and curly haired like her father. She was also an 11th-generation West Virginian, which perhaps explained her mom’s other preoccupation: stopping mountaintop-removal coal mining in Appalachia. Hitt had spent the better part of a decade in Boone, North Carolina, running an organization called Appalachian Voices that sought to end mountaintop removal.

Wading through her backlog of emails after she returned from maternity leave, Hitt was struck by how “defeated and despondent” her fellow environmentalists sounded. She understood why, of course: “We’d just spent a great deal of money, time, and energy trying to pass a climate bill,” an effort that had cost mainstream green groups more than $100 million.

But Hitt’s emails were telling other stories, too—stories that were not getting her Beltway colleagues’ attention. Across the country grassroots activists were defeating plans to build coal-fired power plants, the source of a quarter of America’s greenhouse gas emissions. The movement’s center of gravity was in the South and Midwest, “places like Oklahoma and South Dakota, not the usual liberal bastions where you’d expect environmental victories,” she recalls. (The defeat of the Shady Point II plant in Oklahoma was particularly sweet, coming in the home state of DC’s leading climate denier, Sen. James Inhofe.)

Hitt knew about these victories because she had helped bring them about. In 2008 she had left Appalachian Voices and taken a job as deputy director of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, which aimed to defeat every proposed coal plant, anywhere in the country. “I realized the Sierra Club was winning,” she explains, “and I wanted to win.”

By the time Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) declared the cap-and-trade bill dead in July 2010, the Beyond Coal campaign had helped prevent construction of 132 coal plants and was on the verge of defeating dozens more. It had imposed, noted Lester Brown of the Earth Policy Institute, “a de facto moratorium on new coal-fired power plants.”

To be sure, the activists had help. The recession caused electricity demand to plummet, as did a shift to more energy-efficient appliances, motors, and industrial processes. Why build a power plant, coal or otherwise, if demand didn’t justify it? Coal was also hurt by its own rising costs—especially as natural gas, its chief competitor, stayed relatively cheap.

But those economic trends only made coal somewhat vulnerable, argues Tom Sanzillo, a former New York state deputy comptroller who has worked with the Beyond Coal campaign; it was grassroots activism that leveraged vulnerability into outright defeat. The movement’s strength was grounded in retail politics—people talking with friends and neighbors, pestering local media, packing regulatory hearings, protesting before state legislatures, filing legal challenges, and more. The movement had no official membership rolls; it was populated by clean energy advocates, public health professionals, community organizers, faith leaders, farmers, attorneys, students, and people like Verena Owen, a self-described permit nerd from Illinois who was inspired to oppose coal by a friend who died of lung cancer in her 40s.

“My friend had four boys, just like I do,” says Owen. “I never had to read the news to find out what the air quality was; I could just call her, and if she was having trouble breathing, that told me all I needed to know.” Owen proved so capable, she was recruited to work with Hitt in leading the Beyond Coal campaign.

Stopping new coal plants may be “the most significant achievement of American environmentalists since the passage of the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act” in the 1970s, says Michael Noble of the Minnesota environmental group Fresh Energy. As this article goes to press, 166 proposed coal-fired power plants have been canceled, legally barred, or otherwise stopped from going forward in the United States. That means that each year, 654 million metric tons of carbon, the equivalent of 9.5 percent of US emissions, won’t be entering the atmosphere. The proposed cap-and-trade legislation would, at best, have reduced annual emissions by 16 percent as of 2020. (That’s compared with 2010—though compared with 1990, the baseline used by scientists and international negotiations, cap and trade would have achieved only a 5 percent reduction (PDF).)

See more photos of the River Rouge plant.So why does this landmark shift in the fight against climate change remain unknown to most Americans? Largely it’s because national media and even many environmentalists view the climate issue through the lens of official Washington. When cap-and-trade legislation failed, the conventional wisdom became that the US was simply incapable of taking meaningful action; corporate polluters were too strong, the political system too dominated by industry money, the public too confused and apathetic.

See more photos of the River Rouge plant.So why does this landmark shift in the fight against climate change remain unknown to most Americans? Largely it’s because national media and even many environmentalists view the climate issue through the lens of official Washington. When cap-and-trade legislation failed, the conventional wisdom became that the US was simply incapable of taking meaningful action; corporate polluters were too strong, the political system too dominated by industry money, the public too confused and apathetic.

But the moratorium on new coal shows that Americans “don’t have to wait for Washington to get the country on the right climate track,” Hitt argues. “This campaign has demonstrated we can do this state by state, plant by plant, town by town. Not just that we can do it, but we are doing it.”

That success—a clear demand backed by a grassroots campaign, rather than an incremental, inside-the-Beltway strategy—presents a lesson for organizers, but it also presents challenges as Beyond Coal grapples with the complexities inherent in its name. What will replace the power from the coal plants not being built? How will communities deal with the loss of the taxes they pay, and the decent-paying, often union, jobs they bring? How the movement answers those questions may shape climate politics—including whatever ultimately happens in Washington—for years to come.

Beyond coal’s one moment in the national spotlight came last summer, when on a searing July morning, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg stood before a microphone in Alexandria, Virginia. Behind him, shimmering in the 100 degree heat, loomed the five smokestacks of the Potomac River Generating Station. The plant, which began operating in 1949 and was never required to install modern pollution controls, has been in the crosshairs of local activists for years; shortly before Bloomberg’s appearance, Beyond Coal had released a study that showed its pollution was drifting across the Potomac to Washington, DC. (The plant is now slated to shut down this year.)

Flanked by Hitt and Sierra Club executive director Michael Brune, Bloomberg announced that his personal foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, would contribute $50 million to the campaign’s new push to close existing coal plants. Bloomberg, who has long been passionate about public health (recall his 2006 restaurant trans-fat ban), cited EPA data (PDF) to explain his decision: “Every year, coal-burning power plants like this one cause more than 200,000 asthma attacks nationwide, many of them affecting children,” he said. “Coal pollution also kills 13,000 people every year and costs us $100 billion in medical expenses.

“Thirteen thousand people,” he repeated, “from something that’s planned. And it’s going to happen again next year and the year after, unless we do something about it.”

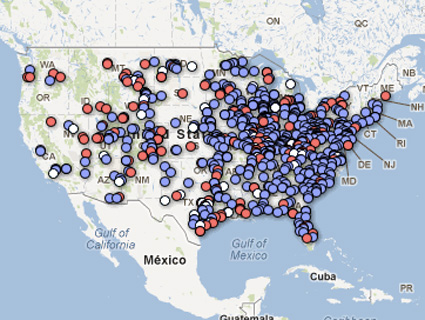

Map: The Cross-Country Fight Against Coal

Bloomberg’s donation will enable Beyond Coal to double down on its second phase—moving beyond blocking new plants to seeking to close a third of the roughly 580 existing ones (PDF) by 2020. The money, says Brune, will help expand the campaign’s paid staff from 102 to 192, including 84 organizers who will be “working on nothing but figuring out how to shut down these plants and replace them with clean energy.”

But boots on the ground are only as effective as the battle plan they are executing. Thus, Beyond Coal will also use some of Bloomberg’s millions to develop a detailed blueprint for the challenge ahead. How can communities that rely on coal move beyond it without committing economic suicide?

It’s not an easy task, Beyond Coal leaders concede. And few places illustrate the difficulty—and the urgency—better than a small town with the deceptively gentle name of River Rouge.

Five minutes south of downtown Detroit, Interstate 75 crests a rise. Below, unfurling for miles on both sides of the highway, is a vast industrial landscape: chemical, steel, and cement factories, a tar sands refinery, a wastewater treatment facility. Webs of piping and wire glint in the sun; smokestacks wheeze skyward; trucks and railcars shuffle back and forth. There are so many factories, packed so densely together, that it’s hard to see the River Rouge coal plant, which sits on the bank of the Detroit River facing the Canadian shoreline.

An acrid odor invades the car. “Actually, the smell isn’t so bad today,” Rhonda Anderson says dryly. Anderson, who grew up in the neighborhood, is the Sierra Club’s environmental justice organizer in Detroit. At 61, she’s nearly the same age as the plant, which at the time of its construction in 1956 was the largest in the world. “My father used to bring me here to play when I was a little girl,” she says as we pull into a parking lot at Belanger Park, adjacent to the plant. “It was the only open space we had.”

The park consists of a lawn, a handful of trees, a fishing pier, and a play structure. Towering over it, barely a football field’s length away, are River Rouge’s three smokestacks, flanked by a mountain of coal 80 feet high. Between the park and the plant is a narrow creek whose bank, incongruously, bears a sign announcing it as a wildlife preserve. It turns out that in 2007 DTE Energy, the plant’s owner, ripped out a sliver of concrete separating the creek from the loading area and replaced it with native plants. In return, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality gave DTE a community service award for making the neighborhood a “cleaner and more attractive place to live and work.”

Never mind that each year the River Rouge plant releases enough mercury, soot, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and other toxic chemicals to cause at least 44 deaths, 72 heart attacks, and 700 asthma attacks, according to studies conducted for the advocacy group Clean Air Task Force. The plant also emits 3.7 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually. The NAACP has called River Rouge the ninth-worst plant in the nation when it comes to health effects on communities of color.

Vincent Martin, whose family fled Cuba and settled in River Rouge, graduated from Southwestern High School in 1980. Of his 150-plus classmates, he says, around one-third have died, “mostly from respiratory illnesses and cancers.” Many of the kids in his neighborhood carry inhalers, he says, and his father, brother, and sister all have asthma.

Of course, it’s difficult to prove that the River Rouge coal plant caused those illnesses, just as it’s difficult to prove that any specific smoker’s lung cancer was caused by cigarettes. And such connections are even harder to draw in a neighborhood crammed with so many polluters that it qualifies as Michigan’s dirtiest zip code.

River Rouge might seem a natural target for the Sierra Club—but so far the club has avoided calling for its closure. It comes down to economics, says Anne Woiwode, the director of the club’s Michigan chapter. Instead, the club is working with unions and community groups to figure out how to replace the jobs and tax revenue River Rouge provides. “Our common interest,” says Woiwode, “is ensuring that when the company walks away from the plant, they don’t just leave the workers and the community behind.”

Meanwhile, DTE seems in no hurry to close River Rouge. John Austerberry, a spokesman for the company, says the plant’s future will be determined by the economic implications of the stricter pollution rules the EPA issued last December. Can the company bring the plant into compliance with those rules and still operate it profitably? “I don’t anticipate we would make that deliberation soon,” says Austerberry. “The rules allow three years” to decide. At 44 deaths a year, that’s 132 more lives.

Kevin Parker, a top executive at Deutsche Bank, has called the coal industry “a dead man walking”—in part because of the increased cost imposed by the Obama EPA’s new regulations. Tom Sanzillo, the former New York deputy comptroller, saw the same vulnerability when he started taking a hard look at the industry. “I knew that if the law was enforced, coal would have a very hard time,” says Sanzillo.

But that was in 2007, when George W. Bush was president and environmental law enforcement was comparatively lax. Back then, Sanzillo—a cheerful, Brooklyn-bred numbers whiz—headed one of the biggest institutional investors in the world, managing $650 billion in assets and serving as the sole trustee of a $156 billion pension fund. In that role, he accepted the conventional Wall Street wisdom that coal was a stable source of predictable profits.

Sanzillo left the job in 2007 and, a few months later, agreed to look into the economics of coal for the Sierra Club. He found that “there were changes going on that I hadn’t understood.” A construction boom in China was increasing demand for steel, cement, copper, and other raw materials. Companies like Bechtel and GE were sending more of their engineers and other specialists to China, raising the cost of such talent back in the States. “It looked like price structures were going to change long term, whereas the price of coal had always been stable,” he says. Adding to the uncertainty was what Sanzillo terms “regulatory havoc”—the new political pressures that stood to increase the cost of burning coal.

The regulatory havoc had grown out of a 2004 meeting of the Midwest’s leading clean-energy activists and philanthropic donors—a network calling itself Re-Amp. Its members confronted a harsh truth, says Fresh Energy’s Noble. They had been working the wrong problem, focusing on renewable energy instead of the broader climate picture. “What does it mean that we celebrate the construction of a $100 million wind farm in Minnesota when at the same time a 900-megawatt coal plant was being built?” asks Noble. “That’s called losing. If you looked at the problem through the lens of carbon, all the work we had done was undone by a single plant—a plant that wasn’t challenged by a single environmentalist.”

The Midwest is the most coal-dependent region in the country; its states get an average of 70 percent of their electricity from coal. (Nationally, it’s 45 percent.) At Re-Amp meetings, Noble joined Bruce Nilles—then a Sierra Club activist in Wisconsin—in arguing that henceforth every proposed coal plant in the Midwest should be challenged. “We didn’t know how we’d oppose them, we just knew we had to,” says Nilles.

At 42, Nilles has leading-man looks that belie his history of tough-nosed activism. Raised in England, he was agitating against nuclear weapons and cruelty to animals before even reaching puberty. After moving to the States during college, he helped organize the first recycling operation at the University of Wisconsin (over administrators’ objections) and went on to serve as an environmental lawyer in the Clinton administration. At one Re-Amp strategy meeting, he tangled with a program officer at one of the Midwest’s largest philanthropies, the Joyce Foundation, who dismissed the idea of opposing every coal plant—it made more sense, the funder argued, to mount tightly focused legal challenges to a few marquee plants.

Rhonda Anderson, with her niece N’Deye, grew up near the River Rouge coal plant, which the NAACP calls one of the worst polluters in communities of color. See more photos of the River Rouge plant.In a universe where activists’ organizations—and paychecks—often depend on the goodwill of foundations, “I was very impressed that Bruce was prepared to go toe-to-toe with a very powerful person and tell him he was wrong,” says Rick Reed, a senior adviser to the Garfield Foundation who helped launch Re-Amp.

Rhonda Anderson, with her niece N’Deye, grew up near the River Rouge coal plant, which the NAACP calls one of the worst polluters in communities of color. See more photos of the River Rouge plant.In a universe where activists’ organizations—and paychecks—often depend on the goodwill of foundations, “I was very impressed that Bruce was prepared to go toe-to-toe with a very powerful person and tell him he was wrong,” says Rick Reed, a senior adviser to the Garfield Foundation who helped launch Re-Amp.

The test of the dueling approaches came in 2005. In opposing a plant in Wisconsin, the Joyce Foundation “put all their chips on a big-bucks legal strategy, with no politics, and lost at the state Supreme Court,” Reed recalls. “That taught us a lesson: You’ll never be able to beat these things without an integrated strategy that includes real people who are affected by these plants, who’ll reject the economic argument publicly.” (The Joyce Foundation, which declined comment for this story, later embraced this idea as well.)

Sanzillo says he saw the value of such an integrated approach in one of the first fights he handled for Beyond Coal. Utilities had proposed two large coal plants in eastern Iowa. Carrie La Seur, an attorney who founded the group Plains Justice, recalls getting phone calls from local people who “didn’t like the idea that there would be this big belching coal plant in the midst of prime farmland, and big transmission lines as well.”

La Seur began submitting legal challenges to the plants. Meanwhile, Sanzillo, testifying about one of the plants before the Iowa Utility Board, made a straight economic argument (PDF): The project would cost far more than the $1.8 billion the company had estimated, and those costs would be passed on to ratepayers for decades. Local activists echoed that message as they met with legislators, Gov. John Culver, and the editorial board of the Des Moines Register. In the end, they persuaded regulators to put a cap on the plant’s cost—any costs above the cap would be absorbed by the company’s shareholders, not ratepayers. Presented with this option, the utility chose to cancel the project.

Arming local people with economic arguments was critical, Sanzillo argues: “If the activists hadn’t been there talking to the regulators and editorial boards and making the case that coal was a bad bet, the [utility board] would have gone forward, because the utilities would say, ‘We can handle the costs,’ and the boards are often good-old-boy boards.”

This approach—hard numbers plus grassroots pressure—became the model Beyond Coal followed in state after state: Wisconsin, Ohio, Florida, even Kentucky, the heart of coal country. In South Carolina, Sanzillo says, activists “put me in touch with small-business associations, and I was able to explain how big industrial interests historically got treated better on these things than small businesses. That was smart, because it got the small businesses fighting with the big industrials, which was just the fight we wanted: a business fight rather than an environmental fight.”

Even the cap-and-trade battle, no matter how unsuccessful, provided economic ammunition. A utility company just might be able to manage coal’s rising construction and fuel costs, Sanzillo explains. Add the prospect of new clean-air regulations from the EPA, and “you might still be able to manage it, but it’s getting dark.” Factor in the possibility that cap and trade might be enacted someday and, “Now, if I’m an investor, Coca-Cola is not looking too bad,” Sanzillo says, starting to laugh. “They give me 10 percent, and I don’t have to worry about climate legislation, the cost of steel in China, and God knows what else.”

None of that makes Beyond Coal’s next task any easier, though: There is a big difference between fighting a proposed plant and seeking to close one that is already providing electricity, jobs, and tax revenues.

“The key is, you don’t do things precipitously,” Sanzillo says. After a wave of deregulation transformed New York’s electricity markets 10 years ago, he notes, many power companies paid less in property taxes. State officials worked with the affected communities “to phase out the loss of the tax base,” sometimes using state money. Nationally, he adds, the same basic principles were applied in the 1990s to help communities cope with post-Cold War military base closures. “The federal government just funded them until the local economies could come back.”

Beyond Coal has helped broker a similar transition in Washington state. When environmentalists first targeted the Centralia coal plant for closure, they ran into opposition not just from its owner, the TransAlta company, but also from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, which represents 150 employees at the plant. “There is no way I or the IBEW would have agreed to shut down that plant,” says Bob Guenther, who worked as a mechanic at Centralia for 34 years before becoming the union’s chief lobbyist, “if we didn’t have an agreement to keep this community whole.”

Beyond Coal has helped broker a similar transition in Washington state. When environmentalists first targeted the Centralia coal plant for closure, they ran into opposition not just from its owner, the TransAlta company, but also from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, which represents 150 employees at the plant. “There is no way I or the IBEW would have agreed to shut down that plant,” says Bob Guenther, who worked as a mechanic at Centralia for 34 years before becoming the union’s chief lobbyist, “if we didn’t have an agreement to keep this community whole.”

As a cofounder of the national BlueGreen Alliance of workers and environmentalists, the Sierra Club had experience working through disagreements with labor, so Beyond Coal made some compromises. “We wanted a 5-year timeline for closing [the TransAlta plant], and we settled for 10,” Nilles says. “Not because of the company but because of IBEW.”

The agreement was hammered out behind closed doors during negotiations requested by Washington Gov. Christine Gregoire. “The governor wanted a deal that would satisfy all sides and avoid litigation,” says Keith Phillips, a senior aide. Phillips spent two days shuttling between rooms containing representatives from TransAlta and environmental groups, but not the IBEW. That left the environmentalists to argue labor’s case—which they did. They insisted that the plant’s workforce be retained throughout its closure and cleanup; that workers be trained in the technologies that would replace coal, especially energy efficiency; and that the company, not the taxpayers, subsidize the transition. TransAlta agreed, pledging $55 million that will be controlled by the affected communities, to fund economic development and clean tech. “A lot of it will pay for insulating schools and other public buildings,” says Guenther. In return, environmentalists accepted a later closure date for the plant: One of its two boilers will shut down in 2020; the other, in 2025.

One big question facing Beyond Coal is what happens if electricity demand begins increasing again. With coal plants so difficult to get approved, utilities might look to natural gas instead, accelerating the environmental devastation caused by gas drilling and fracking. (TransAlta, for one, has announced plans to build a gas plant as it prepares to shut down the Centralia facility.) That dynamic was surely on the mind of Chesapeake Energy, one of America’s largest natural gas companies, when it helped pay for the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign. Between 2007 and 2010, under executive director Carl Pope, the club secretly accepted $26.1 million from the company; Brune, the current executive director, discovered and halted the practice shortly after replacing Pope in 2010. “We can’t take cash from companies or industries that…we want to change,” Brune told me. Nilles says he knew about the Chesapeake money “from the beginning,” noting that the environmental downsides of fracking were not as evident in 2007: “My views on gas have evolved significantly in the intervening years.”

But gas is not the only option for replacing coal. Howard Learner of the Environmental Law and Policy Center in Chicago says technological gains in energy efficiency and renewables are accelerating so rapidly, they may well outpace increase in demand. “Just as it’s hard to imagine a world in which we’re going back to landlines, we’re not going to turn back the clock on energy efficiency,” says Learner. “It’s the best, fastest, cheapest, and most environmentally sound way of meeting our energy needs.” The global consulting firm McKinsey has estimated that efficiency can reduce nontransportation energy use in the United States a full 23 percent by 2020, and that such investments would cost $520 billion while creating $1.2 trillion in savings.

Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute, a sustainability expert who consults with corporations and government agencies around the world, goes even further. In his book Reinventing Fire, he lays out a blueprint for how the United States could stop burning coal for electricity by 2050 while also phasing out oil and nuclear power and still growing the economy by 158 percent. Already, Lovins points out, costs for renewables are falling to the point where wind, especially, is competitive with coal (PDF) for many purposes.

Not everyone projects quite so rosy a scenario. The US Department of Energy estimates that coal’s share of the country’s energy mix will remain relatively steady for decades. And it’s easy to see why: Energy markets (and energy policy) are dominated by corporations that have sunk a lot of investment into fossil fuels.

But the energy sector is also heavily regulated—which means that political shifts can have a fairly immediate effect. And on the political front, Mary Anne Hitt believes the Beyond Coal campaign offers “a fundamental message about how to make change in this country.”

The effort to pass climate legislation, for example, was centered on Capitol Hill, a battlefield where the power of money rigs the system. Then, to satisfy inside-the-Beltway definitions of what was politically realistic, mainstream environmental organizations embraced a policy—cap and trade—that was incremental in its remedy and incomprehensible in its mechanism. “We can’t go out in the streets about that,” one grassroots activist complained at the time. “Most people can’t even understand it.” These strategic choices made it impossible to build the kind of public pressure that could overcome the industry’s political power and deep pockets.

The Beyond Coal campaign, by contrast, organized people around tangible targets: their air, their water, the climate their children would live with. This enabled it to appeal to a constellation of allies (public health advocates, unions) beyond the usual environmental suspects. Finally, Beyond Coal focused on local and state governments, where popular sentiment can have a more immediate effect.

With baby Hazel celebrating her second birthday, Hitt finds comfort in these results. “When you see a coal plant being stopped, that means a mountaintop removal will not go forward and a large amount of carbon will not be released into the atmosphere—you can see you’re making a difference,” she explains. “As a parent, that makes it easier for me to sleep at night.”