Susan Walsh/AP

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

One of America’s most powerful and outspoken opponents of climate change regulation received election campaign contributions that can be traced back to senior BP staff, including chief executive Bob Dudley.

Jim Inhofe, a Republican senator from Oklahoma who has tirelessly campaigned against calls for a carbon tax and challenges the overwhelming consensus on climate change, received $10,000 from BP’s Political Action Committee.

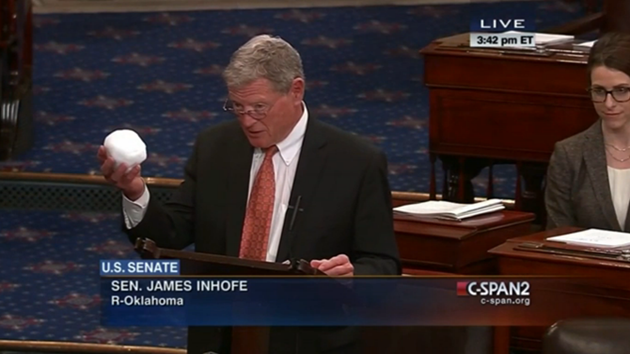

Following his re-election, Inhofe became chair of the Senate’s environment and public works committee in January, and then a month later was featured in news bulletins throwing a snowball across the Senate floor.

Before tossing it, the senator said: “In case we have forgotten—because we keep hearing that 2014 is the warmest year on record—it is very, very cold outside. Very unseasonal.”

The BP PAC is funded by contributions from senior US executives and company staffers who sent in contributions to the PAC totaling more than $1 million between 2010 and 2014. Over the same period the committee paid out $655,000 to candidates, with more than 40 incumbent senators benefiting.

Yet, BP and Dudley have long called for world leaders to intervene and impose tough regulatory measures on the fossil fuel industry. Publishing its 98-page research paper, Energy Outlook 2035, last month, BP warned: “To abate carbon emissions further will require additional significant steps by policymakers beyond the steps already assumed.”

Dudley has personally given $19,000 since June 2011 to the BP PAC—very close to the $5,000-a-year maximum allowable by law. Although Dudley is a resident of Britain, he is eligible to give via the BP PAC because he is a US national.

While the sums channeled to Inhofe’s campaign represent only a small proportion of the BP PAC’s election spending and the senator’s own campaign funds, they show how unafraid the committee has been to spread its donations to the most controversial candidates. According to the BP PAC website, it financially supports election candidates “whose views and/or voting records reflect the interests of BP employees.”

Records suggest Inhofe’s 2014 campaign was a funding priority for the BP PAC, ranking as one of the top recipients of committee funds when compared with disbursements to other serving senators.

This was despite Inhofe’s senate battle not being a close one. His opponent, Matt Silverstein, who Inhofe beat comfortably in last November’s midterms, had a tiny campaign war chest by comparison.

BP was asked whether it was appropriate for the PAC to make campaign contributions to such a vocal opponent of action on climate change, or for Dudley to be contributing towards such payments.

In a statement BP replied: “Voluntary donations [by staff] to the BP employees’ political action committee in the US are used to support a variety of candidates across the political spectrum and in many US geographies where we operate.”

“These candidates have one thing in common: They are important advocates for the energy industry in the broadest sense.”

It added: “BP’s position on climate change is well known and is long-established. We believe that climate change is an important long-term issue that justifies global action.”

The company declined to comment on Dudley’s own donations.

PACs exist in the US where companies and trade unions cannot give directly to the campaigns of those running for office. Instead funds are pooled from staff—often senior executives—into a PAC, and disbursed by a committee board, often in a manner sympathetic to the company’s lobby and other interests.

Other US oil industry leaders, including Exxon Mobil chief executive Rex Tillerson, make contributions to their own corporate PACs—money which in many cases can then be traced to Inhofe and other climate-skeptic politicians.

But Tillerson and other peers have not been as outspoken as BP and Dudley in calling for state intervention to tackle climate change, making the BP boss’s links to Inhofe campaign finance more controversial.

Last week Obama said it was “disturbing” that Inhofe had been made chair of the senate environment committee. In broader criticism of unnamed political opponents, he then went on to say: “In some cases you have elected officials who are shills for the oil companies or the fossil fuel industry. And there is a lot of money involved.”

Inhofe is unabashed about election campaign financing he receives from the industry. In his 2012 book, The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future, he wrote: “Whenever the media asked me how much I have received in campaign contributions from the fossil fuel industry, my unapologetic answer was ‘not enough.'”

According to data compiled from public filings by the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP), Inhofe’s campaign raised $4.84 million between 2009 and 2014, with $1.77 million coming from PACs, many of them sponsored by fossil fuel companies.

BP’s PAC was more active in the US 2014 election cycle than any other for more than a decade. Despite insisting it is non-partisan, 69 percent of contributions to federal election candidates in recent years have been to Republican politicians. This is a stronger bias than most other corporate PACs, according to the CRP.

Not all recipients of BP PAC donations are climate change skeptics. Indeed, among other top recipients in recent years has been Steny Hoyer, House Democratic whip, one of the strongest advocates for government measures to tackle climate change.

There are, however, other leading recipients who have attracted criticism from climate change campaigners, including Republican House speaker John Boehner and fellow Republican, Sen. Mike Enzi from Wyoming.

When asked his views on climate change in January, Boehner said: “We’ve had changes in our climate, although scientists debate the sources, in their opinion, of that change. But I think the real question is that every proposal out of this administration with regard to climate change means killing American jobs.”

“I don’t see [Obama] as trying to control pollution. I see him trying to put business out of business,” Enzi said last year.

Campaign contributions are just one aspect of US political engagement linked to BP and its staff. Filings show the oil and gas group spends millions on lobbying efforts.

The CRP classifies BP as a “heavy hitter,” ranking it among the top 140 biggest overall donors to federal elections since 1988. Its PAC ranks as the sixth largest such body with a sponsor company that is ultimately part of a non-US multinational company.

Those on the PAC board, deciding how to spend staff donations, are senior executives and lawyers at the company. The board’s vice-chair is Bob Stout, BP’s Washington-based head of regulatory affairs, who also sits on the group’s global policy making body. Dudley does not sit on the PAC board.

According to its website, the PAC makes donations to “candidates who support the principles of free enterprise and good government, support a fair and reasonable business environment for the energy industry and share our philosophy that energy diversity advances energy security.” It says staff contributions are encouraged but stresses they are voluntary.

The first BP PAC contribution to Inhofe’s 2014 campaign was a given on March 12, 2012. This $1,000 donation came just two weeks after the publication of Inhofe’s book The Greatest Hoax, cementing his credentials as the most outspoken denier of climate change in US politics.

Publicizing the book, the senator gave a radio interview on Voice of Christian Youth America. “God is still up there,” he said. “The arrogance of people to think that we, human beings, would be able to change what he is doing in the climate to me is outrageous.”