Zentilia/Shutterstock; Vitaga/Shutterstock

For the past few years, tiny Doyline, Louisiana, best known as the Southern Gothic setting of HBO’s True Blood, has been perched next to a powder keg. Next month, the Environmental Protection Agency will decide whether to light a match.

In 2012, an explosion at Camp Minden, a former military base just outside of town that had become a hub for munitions contractors, sent a 7,000-foot mushroom cloud into the Louisiana sky. The blast rattled homes as far away as Arkansas and forced Doyline residents to evacuate. “I thought I was in Afghanistan,” one resident told the Associated Press. State police investigators, who raided Camp Minden soon after, discovered that Explo Systems Inc., a munitions recycling company that operated there, was storing 15 million pounds of toxic military explosives on-site—with some of it in in paper sacks, cardboard boxes, or even outside. After the raid, the company, at the direction of state officials, moved the munitions into old bunkers the Louisiana National Guard had made available on the base in order to reduce the risk of an explosion caused by a fire or a lightning strike.

A Louisiana grand jury indicted seven Explo employees on multiple charges, including unlawful storage of explosives and conspiracy. (The case has not yet gone to trial.) Two months later, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms revoked Explo’s explosives licenses. The next week, the company declared bankruptcy, triggering a fight among state and federal regulators over whose job it was to clean up the toxic mess.

Now the race is against the clock. The bunkers are falling apart—pine trees are growing on the roofs of several of them—which means the increasingly unstable materials are now being exposed to moisture. And the EPA has warned that the explosives, which become more unstable over time, are increasingly at risk of an “uncontrolled catastrophic explosion.” So in October, the EPA announced it would do something it had never done before—approved a plan for a large-scale controlled burn of the hazardous military waste.

That came as a shock to local residents, who had not been consulted on the plans and begged Congress to intervene. The result has been an unusual standoff in which conservative lawmakers, led by Sen. David Vitter (R-La.), have joined hands with environmentalists to accuse the Army and EPA of jeopardizing the public health and safety of a rural Louisiana parish. On January 15, in response to the backlash, the EPA announced it would put its plans on ice for 90 days and consider alternative options. A decision is due by mid-April.

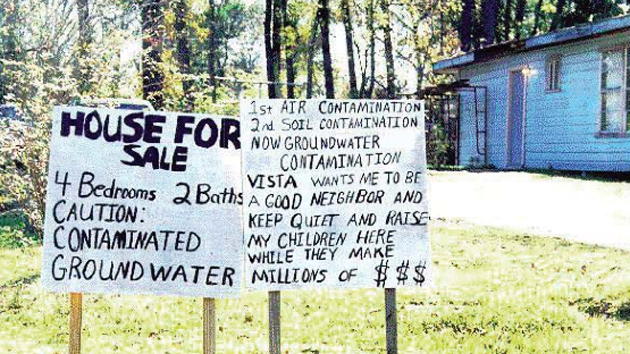

Residents of Webster and Bossier Parishes are just as concerned about the long-term health effects of a burn as they are the consequences of an unexpected blast. TNT, which can cause liver and blood problems, seeped into the soil around the base during its years as a bomb-making facility—contamination that predated Explo System’s lease of the land. Now, residents worry that the EPA will make the contamination problems worse. The explosives the EPA wants to burn include millions of pounds of M6, an explosive propellant that contains large amounts of DNT, which the EPA’s own data associates with a higher risk of heart disease and nervous-system damage. And a burn won’t get rid of everything. Brian Salvatore, a chemist at Louisiana State University-Shreveport who has become a leading opponent of the burn, argues that a substantial percentage of the M6 will simply be released into the air—and back into Doyline.

The history of Camp Minden has done little to inspire Louisianans’ confidence that the authorities will deal with the problem responsibly. The Department of Defense’s contract management agency made weekly visits and quarterly inspections in the years leading up to the 2012 incident. But those safety inspectors later told investigators they never ventured into the storage areas, and were accompanied at all times by Explo staff. Nor did they audit the materials that were being kept in the facility, allowing the company to accumulate explosive waste well in excess of what it was permitted to handle. In its final inspection, six weeks before the blast, a DOD representative gave Explo System clean marks—just as inspectors had done after every inspection for the previous three years.

There was reason for scrutiny. In 2006, a series of 10 explosions at the Explo plant there caused the evacuation of the entire town of Doyline—including two schools and 441 inmates from the Webster Parish jail—and shut down Interstate 20 for six hours. And 10 days before that, a series of explosions at a nearby military flare manufacturer, also based at Camp Minden, shut down production at the site for more than a month. Explo’s out-of-state operations also had issues. One worker was injured and others exposed to toxic materials at a West Virginia surface coal mine in 2007 where Explo Systems had supplied outdated military explosives for mountaintop removal. (The company was slapped with six federal mine safety violations, totaling $12,000.) But Explo continued to receive Army contracts.

Vitter criticized the EPA’s plan in a letter to the agency in October, and again in January, when GOP Sen. Bill Cassidy and Reps. John Fleming and Ralph Abraham signed on to a second letter. The lawmakers demanded “assurances that human health and environmental impacts on the air, water, and soil will be continually monitored throughout the process.” Shortly after that, the EPA announced it would put its plan on hold and solicit alternative ideas.

Now the agency is in the middle of its 90-day review period. If the EPA decides to go forward with the open burn, the Louisiana National Guard has to find a contractor to prepare the site and conduct the burn. If the EPA decides to try something new, it has to work out a new agreement with the state and the Army before it can do anything else.

But if there’s a viable alternative to the open burn, no one’s agreed on it yet. A review by the Department of Defense Explosives Safety Board concluded that each of the proposed alternatives—such as transportation to a new disposal site or demolition—would be even more time-consuming, too small-scale, or too risky.

As the deadline approaches, activists are ramping up the pressure. On Wednesday, Lt. General (Ret.) Russel Honoré, who led the military response to Hurricane Katrina and has reemerged as an environmental-justice activist, held a rally in the town of Minden, just north of the site, hitting a familiar theme—that the needs of poor communities in the state are consistently ignored when it comes to the disasters in their backyards. Frances Kelley, a Shreveport native who serves on the EPA’s dialogue committee, says that if the government goes forward with its original plan, residents may resort to a physical occupation of the site to prevent an open burn.

“I think we can all appreciate this is a pretty unique circumstance,” says EPA spokesman David Gray. “To have this quantity, abandoned, by a company that was acting criminally, that was left in the neighborhood and on the doorstep of a state agency.”

Shortly after the Louisiana State Police raided Explo’s site, the state asked the Army to inspect the abandoned materials. The result was ominous—a task force reported back that an explosion at the site was “likely,” due to the deteriorating condition of the propellants. But just how likely is impossible to know. In a bit of a catch-22, a subsequent EPA report explained that no one had even been able to set up a program to monitor the stability of the explosives, because that would require moving them—which no one wants to do, because no one knows how stable they are.

The Army’s best guess for when the materials would become serious risks for self-combustion was August of 2015.