Over the last two years, about 5 percent of the world's coral reefs have died forever. The outlook for 2016 appears even worse.<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-58975162/stock-photo-environmental-problem-dead-coral-reef-killed-by-global-warming-and-pollution.html?src=kr85kYCvGHsZNamjeTpjrg-1-2"Rich Carey</a>/Shutterstock

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Scientists have confirmed the third-ever global bleaching of coral reefs is under way and warned it could see the biggest coral die-off in history.

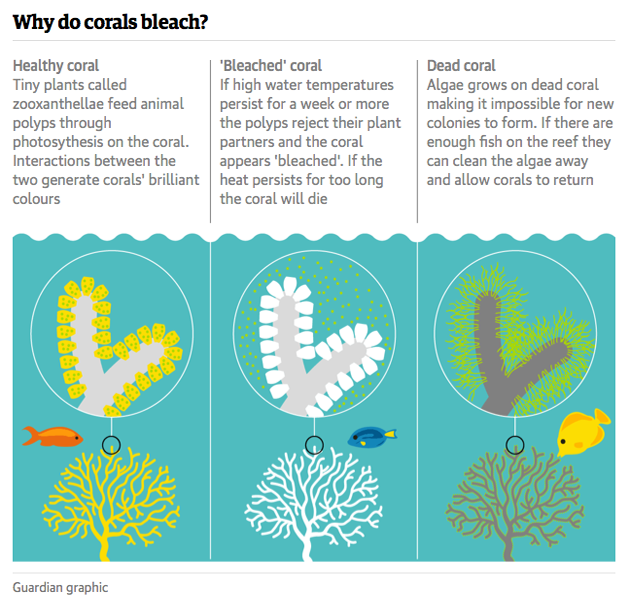

Since 2014, a massive underwater heat wave, driven by climate change, has caused corals to lose their brilliance and die in every ocean. By the end of this year 38 percent of the world’s reefs will have been affected. About 5 percent will have died forever.

But with a very strong El Niño driving record global temperatures and a huge patch of hot water, known as “the Blob,” hanging obstinately in the north-western Pacific, things look far worse again for 2016.

For coral scientists such as Dr. Mark Eakin, the coordinator of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Coral Reef Watch program, this is the cataclysm that has been feared since the first global bleaching occurred in 1998.

“The fact that 2016’s bleaching will be added on top of the bleaching that has occurred since June 2014 makes me really worried about what the cumulative impact may be. It very well may be the worst period of coral bleaching we’ve seen,” he told the Guardian.

The only two previous such global events were in 1998 and 2010, when every major ocean basin experienced bleaching.

Professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, director of the Global Change Institute at the University of Queensland, Australia, said the ocean was now primed for “the worst coral bleaching event in history.”

“The development of conditions in the Pacific looks exactly like what happened in 1997. And of course following 1997 we had this extremely warm year, with damage occurring in 50 countries at least and 16 percent of corals dying by the end of it,” he said. “Many of us think this will exceed the damage that was done in 1998.”

After widespread devastation was confirmed in the Caribbean this month, a worldwide consortium of coral scientists joined on Thursday to somberly announce the third-ever global bleaching event—and warn of a tenuous future for the precious habitat unless sharp cuts were made to carbon emissions.

Since the early 1980s the world has lost roughly half of its coral reefs. Hoegh-Guldberg said the current event was directly in line with predictions he made in 1999 that continued global temperature rise would lead to the complete loss of coral reefs by the middle of this century.

“It’s certainly on that road to a point about 2030 when every year is a bleaching year…So unfortunately I got it right,” he said.

Hoegh-Guldberg said he had personally observed the first signs of bleaching on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef in the past fortnight, months before the warm season begins. He said the warming pattern indicated bleaching this summer would likely affect 50 percent of the reef, leaving 5 to 10 percent of corals dead. Eakin said seeing bleaching on the reef at this time of year was “disturbing.”

“We are going to have to double our efforts to reduce the other threats to the reef,” said Hoegh-Guldberg of the icon that UNESCO has considered listing as World Heritage in Danger, due to the threats of a mooted coal port expansion, agricultural run-off and climate change. “It’s like a hospital patient. If you’ve got a chronic disease then you are more sensitive to a lot of other things and if you want a recovery then you need to take all those other stresses off.”

The difference between this bleaching event and others before it is not just the extremity of sea temperatures, but how long they have persisted for. Corals can recover from bleaching if the temperature relents. But after a month or more the organisms that build these brilliantly colored underwater cities die.

“This is not only a big event, but it’s more persistent than any of our past ones, including 1998,” said Eakin. In many areas the bleaching has now lasted far longer than the threshold month and in Hawaii, Guam, Kiribati and Florida there has been back-to-back bleaching events across the past two years.

Like rainforests on land, coral reefs are home to a riot of biodiversity. On just 0.1 percent of the ocean’s floor they nurture 25 percent of the world’s marine species. The impact of losing this would be devastating for the 500 million people who rely on coral ecosystems for their food and livelihood. These effects would not be felt immediately, but over the coming years as fish species move on or die off.

“It really does affect things like tourism and fishing,” said Hoegh-Guldberg. However, he said there was still hope, if governments acted immediately to relieve both global and local pressures on reefs.

“If we were to take strong action on the emission issue and we were to take strong action on the non-climate issues such as overfishing and pollution, reefs would rebound by mid to late century,” he said.