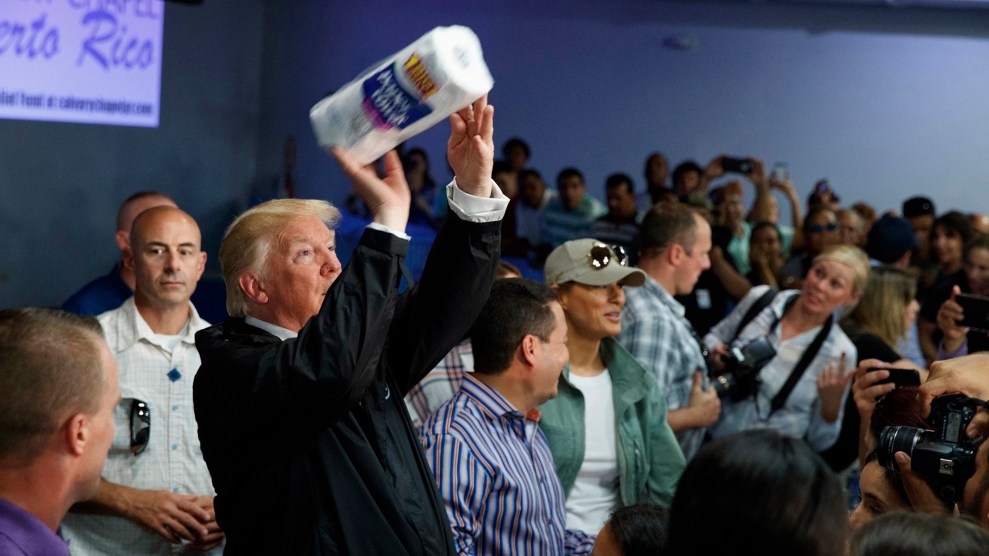

President Donald Trump visits Puerto Rico after Hurricanes Irma and Maria.Evan Vucci/AP

As hurricane after hurricane ravages Puerto Rico and the Gulf Coast, the Trump administration has quietly walked away from a government-wide effort to help the growing number of American communities whose very existence is threatened by climate change.

In the final year of the Obama administration, nearly a dozen federal agencies—led by the Department of Housing and Urban Development—began laying the groundwork for a cohesive federal approach to the so-called climate refugee problem. In December 2016, a top HUD official signed a memorandum of understanding, which would have committed these agencies to work together to develop a strategy for relocating homes, infrastructure, and—in some cases—entire municipalities put at risk by rising seas, melting permafrost, and more dangerous storms.

But since then, the group has done nothing, according to current and former officials familiar with the effort. No other agency appears to have signed off on HUD’s plan, and it has never gone into effect.

It might not be surprising that a president who calls global warming a Chinese hoax would be slow to address its impacts. But for those in the most vulnerable parts of the country, there’s no time to wait. With each severe storm comes the prospect of evacuation and destruction. Thousands are left temporarily displaced or stranded. This cycle, made worse with climate change, is becoming too much for some residents; relocation may soon be their only option. But without a clear government plan to address the problem—and pay for a solution—finding a new home will be all but impossible.

The road connecting Isle de Jean Charles to the mainland floods for days at a time.

Kyla Mandel (Flight made possible by Southwings)

Nowhere is the problem of climate dislocation more apparent than on Louisiana’s Isle de Jean Charles, which was hit by Hurricane Harvey on August 30. Residents there were cut off from the mainland, their only road off the small bayou island submerged beneath the Gulf. This is actually nothing new; the road often floods for days at a time during storm season. Next time could be a lot worse.

When I visited Isle de Jean Charles earlier this year, fat drops of rain were beating down in the yard of Chief Albert Naquin. “You want to know what we’re going through?” he said, sitting on a swinging couch inside his office—a square veranda set up in his driveway. “We’re going through a lot of red tape. A lot of bureaucracy. That’s why I wear a red shirt.”

This January will mark two years since HUD made headlines by awarding Louisiana $48 million to move Naquin’s entire community off of the island, a sliver of land just a quarter-of-a-mile wide and less than two miles long that is slowly being swallowed by the Gulf of Mexico. It was the first federal grant intended to move an entire community of climate refugees.

For nearly 20 years, Naquin has been trying to relocate his Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe. A mere 320 acres are all that remain of the island, down 98 percent since 1955, thanks to a combination of erosion and sinking land, rising seas, and more intense storms. Until a new community is built, though, the tribe remains on the island.

“This is our second hurricane season since we received the money,” said Naquin, as he complained about the glacial place of government. “Even the big turtles can walk faster than them. The snails can walk faster than them.”

But as frustrated as they may be, the residents of Isle de Jean Charles are actually among the lucky ones. Their HUD grant has already gone through, and even the Trump administration hasn’t tried to block it.

Beyond Louisiana, native communities along the coasts of Alaska and Washington state have also spent decades wading through the muddy waters of bureaucracy and a tangled network of grant programs, searching for help to move to safer ground. They’ve had much less success. It was only during the final months of the Obama administration that the government began tackling the issue of climate relocation on a national scale. Now, under Trump, even that limited progress is in jeopardy.

Isle de Jean Charles has lost 98 percent of its land since 1955.

Kyla Mandel (Flight made possible by Southwings)

Long before the widely criticized response to Hurricane Maria, government officials privately conceded that the feds simply aren’t doing enough to help communities facing climate catastrophe. “We’re in a state of active learning,” one former government staffer told me in March. “We know it’s happening, and it will more and more, but we haven’t had an organized approach…We saw Katrina, and what happens when you react instead of plan. It’s more of a mess.”

There is also an endless string of costs associated with integrating communities into a new area, from infrastructure to social services and health care. “It’s massive and all at once,” the staffer said. “We’re just not prepared.”

If you add up the estimates that exist for how much it would cost to move just five small villages that are currently seeking relocation—about 2,185 people in three states—the price tag comes to roughly $500 million.

But that’s just the beginning. Thousands of people never returned to New Orleans after Katrina. Many fled to Houston, where some of them faced disaster once more when Harvey struck. Tens of thousands of people could leave Puerto Rico in the wake of Irma and Maria.

In less than 30 years, roughly 1 million Americans living in coastal areas will already be dealing with about 1 foot of sea level rise. Scientists project that by the end of the century, seas could rise by as much as 3 feet. That would leave more than 4 million people at risk of flooding, according to one recent study in Nature Climate Change. There are no official estimates for how much this would cost the country. My back-of-the-envelope math puts the price of relocation for those five villages at $239,000 per head. Multiply that by the number of people at risk nationwide by the end of the century, and the total price tag could surpass $1 trillion. The Nature study suggests it could be even higher: $1 million per person.

Despite these costs, for years there was no federal strategy to tackle climate-driven human displacement.

Near the end of the Obama administration, this began to change. In February 2016, 11 federal agencies and departments—led by HUD and the Department of Agriculture—started discussing climate migration. Together, they wanted to determine what sort of role there should be, if any, for the federal government. The agencies met for the first time in April 2016 and, under the guidance of the White House Council on Environmental Quality, began to draft a memorandum of understanding.

The memorandum, obtained via the Freedom of Information Act, states that the agencies planned to “work together to collaborate to support communities’ migration away from vulnerable areas, particularly those threatened by recurring natural disasters and the cumulative effects of severe environmental changes.” (You can read the memorandum at the bottom of this story.)

The purpose was to create a more coordinated approach and help agencies assess the best way they could work with affected communities. According to the former government staffer, the idea was to bring together different funding streams in order to make the administrative process for communities easier. “It’s about fiscal responsibility, human safety, and planning,” the former staffer said. “It’s about moving people out of harm’s way when they’ve decided that’s their best option.”

The memorandum did not prescribe any specific policy, nor did it formally establish federal responsibility for tackling climate migration. But it was a start. It laid out a plan for the interagency working group to meet every other month. Within nine months, the group was supposed to have developed a multiyear strategy to achieve its goals.

The aim, said National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration official Jeff Payne, was to have the entire thing “signed, sealed, and delivered” before the Trump administration took over. But that doesn’t appear to have happened. Nine months into Trump’s term, the memorandum has never taken effect.

I reached out to all 11 agencies involved, as well as to the White House. Most, including a White House spokesperson, referred me back to HUD or the interagency group. The Department of Agriculture, which, according to the memo, was supposed to chair the working group, said it was “not familiar” with the plan. The Environmental Protection Agency said that it is “not actively involved in this work.” According to both Payne and a former federal employee under Obama and Trump who was involved in the effort, the working group has not met since Trump took office. It seems unlikely that it ever will.

So, while the roadmap still exists, the coordinated approach will be lost. With Obama’s staff leaving “and the lack of direction from the new administration on what it wants to do in this domain, it is not clear when things may pick up, if at all, on this,” Payne told me.

Meanwhile, some agencies have tried to get a sense of what programs they have available to help vulnerable communities. Staffers at HUD even began drafting a memo to present to senior leadership to discuss the scale of the risk, all without using the words “climate change,” according to the former federal employee who was involved in the working group. (HUD Secretary Ben Carson told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2015, “There is no overwhelming science that the things that are going on are man-caused and not naturally caused. Gimme a break.”)

The most likely outcome, though, is that the memorandum will continue to lie dormant. Maybe it will get picked up again under a friendlier administration. But for some, four years is too long to wait. “There are communities that need help right now,” says Payne. “They’re struggling, they’re asking, and the resources to assist them are…very limited.”

And this season’s hurricanes haven’t helped, Payne explained in an email: “They have likely amplified the risk and vulnerability of some populations, including low-income folks where impacts and the ability to recover are likely beyond their current means barring any federal or other assistance.”

Back on Isle de Jean Charles, residents are still waiting for the next step: acquiring a plot of land where they can build their new community. Together with the state, they are in the process of securing a new site, which sits on higher ground inland. Next come the environmental assessments and negotiating the purchase agreement.

The island has less than 50 years left before it’s expected to be almost entirely inundated. But it will be uninhabitable before then. “It’s Mother Nature against man,” said Chris Brunet as he sat underneath his house, the foundation and floorboards raised above his head by 11-foot-tall wooden posts that protect them from flooding. “The Gulf of Mexico, it’s just so powerful and it wants to come in. And that, with the coastal erosion, with the land loss that’s taken place, it just seems like it can’t hold it back anymore.”

“If nothing is done to change that,” he added, “well, then it’s just bound to get worse.”