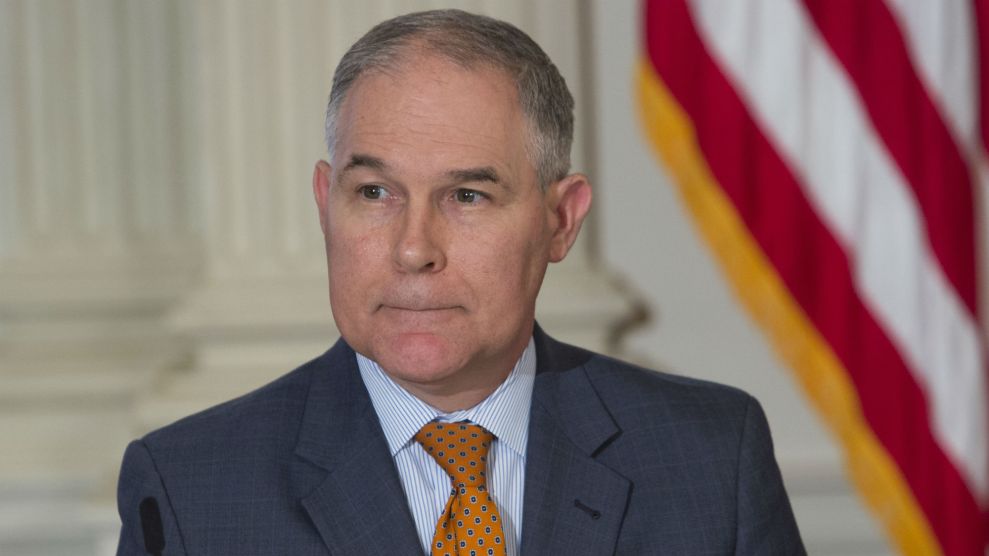

Mother Jones; Andrew Harnik/AP

If EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt survives the onslaught of accusations of mismanagement and excessive spending with his job still safe, he has his biggest benefactors to thank. The #StandWithScottPruitt campaign has flooded the White House with pleas from Trump donors and conservative and industry-aligned groups to defend Pruitt, chalking up the revelations about his ethics scandals to a “smear campaign” from the “radical left.”

Pruitt, technically, can be easily replaced because the fossil fuel industry now has an ally in the EPA’s number two spot. Andrew Wheeler, a recent coal lobbyist who used to work for the Senate’s biggest climate change denier, would take over as acting administrator should Pruitt leave.

So, why is Pruitt still so valuable to Trump donors like Harold Hamm, the Oklahoma oilman who chaired Pruitt’s attorney general reelection campaign and called Trump last week?

The answer doesn’t appear to be that Pruitt is a legal genius who has rapidly and effectively gutted regulations in a way that satisfies the courts. “They’re producing a lot of short, poorly crafted rulemakings that are not likely to hold up in court,” Richard Lazarus, a professor of environmental law at Harvard, told the New York Times. Six of his regulatory rollbacks have already been struck down, the NYT adds. Natural Resources Defense Council’s David Doniger has also argued that many of Pruitt’s regulatory rollbacks are still “years away from being done”

But the right wing doesn’t just think Pruitt is efficiently reversing regulations to reduce the EPA to “little tidbits”; they’re happy with his all-out assault to hollow out environmental oversight and enforcement. “Pruitt is the most conservative member of the cabinet, both in temperament and action,” Republican strategist Mike McKenna told Bloomberg. Indeed, he’s always been seen as a “conservative icebreaker” by Oklahomans in his home state.

Pruitt isn’t just valuable to his base—the industries he regulates—for the formal actions he’s taken on the regulatory front, even if they are likely to get tied up in litigation. Former EPA attorney Joseph Goffman, Harvard Environmental Law’s executive director, has been tracking the dozens of air, water, and climate regulations Pruitt has taken aim at so far. And Goffman has a counterargument: Pruitt has undermined environmental protection in ways that are not so easy or straightforward to untangle with a lawsuit.

“He certainly sent the signal that in any given instance his policy preference is achieving lower levels of pollution reduction and achieving pollution reduction on a slower schedule,” Goffman says.

Those signals matter, Goffman continues, because “it’s to the advantage to any individual company to know all its competitors are playing by the same rules,” and when the baseline is lowered, companies have little reason to adopt new pollution controls.

Take one example: Pruitt canceled an information request last year that required oil and gas companies to submit a range of data about how to reduce their methane leaks to the EPA. The oil industry, which announced a string of voluntary initiatives to reduce methane in the Obama administration as it looked ahead to regulation, now has little incentive to deal with these leaks. Now that it’s stalled, there is still limited information about industry methane leaks.

“Had it been collected, the agency would have had a rich store of new information and new data to reduce methane from the oil and gas sector,” Goffman says. “The concept of sending signals goes beyond rhetoric, and it goes to all sort of investment decisions that polluting sources and tech investors make pretty far upstream, depending on whether they expect the EPA to be moving forward to implement or enforce.”

For all his controversy and bluster—he’s known to issue press releases and go on the conservative media circuit to tout things before they happen—after only 14 months he’s left damage that may be difficult to ever repair. He’s overseen a stark drop in enforcement fines against polluters, plus he’s appointed industry-friendly advisers to the EPA’s science advisory boards, reshaping how the agency studies science. He’s expected to sign a directive soon that bars the agency from using a wide range of public health studies in crafting regulations. The EPA used to have up-to-date information about the state of climate change science; now, one must dig through the Obama EPA archives to pull out information that is no longer updated. He’s driven out experts on staff, leaving major gaps in programs that the EPA oversees—it will be a long slog for a new administration to recruit and train staff to refill these roles.

“It’s the work that’s not being done that’s having the biggest impact,” Goffman says.