Tesoro Oil Refinery, Anacortes, Washington State, USAKevin Schafer/Getty

This story was originally published by HuffPost. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The world’s top 10 fossil fuel-producing countries are on track to extract far more oil, gas and coal by 2030 than scientists say the planet can handle without experiencing catastrophic warming, according to a report published Wednesday.

The first-of-its-kind analysis―conducted by scientists at six organizations, including the nonprofit Stockholm Environment Institute and the United Nations Environment Programme―measured for the so-called production gap between the goals set in the 2015 Paris climate accord and projections for fossil fuel production in China, the United States, Russia, India, Australia, Indonesia, Canada, Germany, Norway and the United Kingdom.

The findings lay bare a stark contradiction between the amount of climate-changing emissions nations pledged to cut over the next decade and many of those countries’ plans to expand fossil fuel drilling, which “further hinders the collective ability of countries to stabilize the climate system, including closing the emissions gap,” the report stated. The assessment, the scientists said, suggests tighter restrictions on fossil fuel production are urgently needed to avert climate disaster in the decades to come.

“The discrepancy between national policies―the climate change policies and fossil fuel production policies―highlights there is much more that needs to be done both at country level and international climate negotiations to put a sharpened and increased focus on fossil fuels,” Niklas Hagelberg, the UN Environment Programme’s climate change coordinator, said on a call with reporters Tuesday morning.

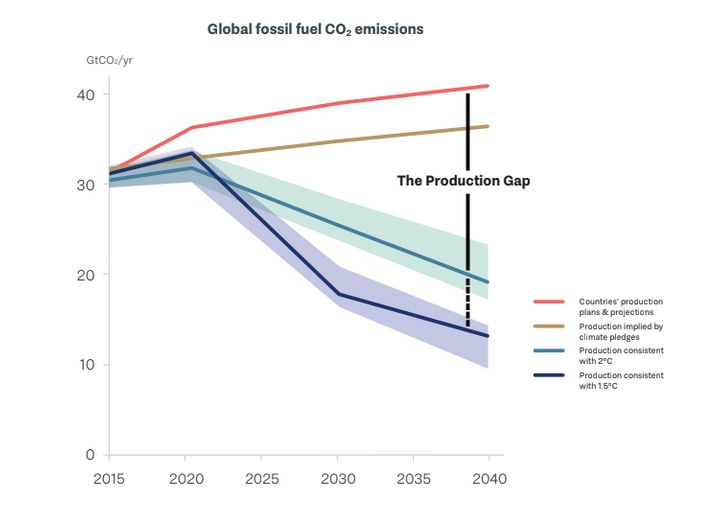

Assuming the fuels extracted will be burned, the combined oil, gas and coal production is on pace to be 50 percent higher than would be consistent with a goal to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial averages―the target to which nearly every country on Earth agreed in the Paris Agreement. Coal mining alone is 150 percent greater than the production goal that would keep warming in that zone, despite the conventional narrative that coal production is declining.

A chart from the report shows the so-called production gap between the emissions cuts needed to keep global warming in a safe range and the amount of fossil fuel projected to be extracted.

SEI

The numbers are even starker when it comes to keeping average temperatures from exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), the threshold beyond which United Nations scientists last year projected hundreds of millions would die and islands and coastal cities would face catastrophic sea-level rise. Fossil fuel production overall is 120 percent higher than would be consistent with a 1.5 degrees scenario. Coal projections are 280 percent higher.

The report does not break down the production gap on a national level. Determining which countries bear the most responsibility for reducing fossil fuel output is an ethical question, scientists say. But the United States―already the world’s No. 2 coal producer and, as of last year, the top oil producer―was already on pace to produce 60 percent of the world’s newly tapped supply of oil and gas by 2030, according to a January report by scientists at more than a dozen environmental groups.

That reality is reflected in the country’s production gap.

“It’s at least as big if not bigger than the global average,” Michael Lazarus, a senior scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute and lead author of the report, told HuffPost by phone.

There are some promising signs. The report said supply-side restrictions, including production bans in countries like France and New Zealand, offer a model of how to quickly scale down new extraction. Eliminating century-old subsidy programs for fossil fuels could make a considerable dent in production. Without subsidies, nearly half of U.S. oil wells would cost more to drill than to abandon if crude were priced at $50 per barrel, a 2017 Stockholm Environment Institute study found. The fossil fuel industry received a combined $5.2 trillion in incentives across the world, according to a startling International Monetary Fund estimate published in May.

“Phasing out this support will make oil, gas and coal uneconomical,” said Ivetta Gerasimchuk, a co-author of the report and energy program director at the Geneva-based think tank International Institute for Sustainable Development. “We use the comparison for calling these subsidized projects ‘zombie energy.’ Without government support, these projects would be dead.”

Still, she warned that blanket bans are in some cases “politically easier” than revoking subsidies that are “very much entrenched.”

Such rapid and radical economic changes, the authors said, require programs to transition workers in fossil fuel industries to new jobs. The report listed so-called “just transition” efforts in China, Spain and New Zealand as examples of proactive policy measures. In the United States, roughly half a dozen Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidential nomination have proposed variations of a Green New Deal, which offers another potential model for such a change.

But such a federal program is all but impossible under the current White House, which denies climate science and began the process this month of formally withdrawing from the Paris Agreement altogether.