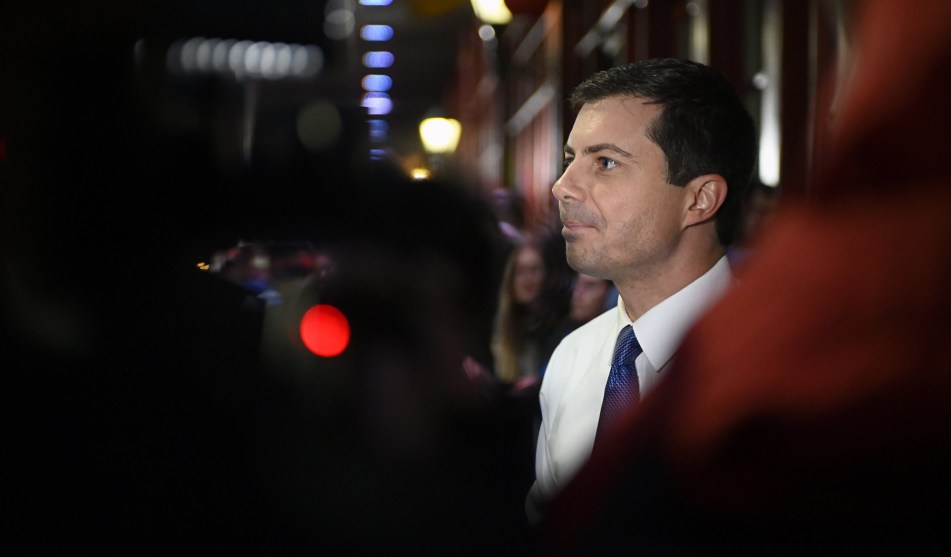

Democratic presidential candidate South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg has lunch with a few supporters at Panaderia on November 26, 2019 in Denison, Iowa.Scott Olson/Getty

Democratic presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg released a white paper on Monday focused on a slew of policy proposals aimed at Latinx voters. Entitled “El Pueblo Unido/A People United: A New Era for Latinos,” the 20-page document explores how a Buttigieg administration would address access to voting, a lack of affordable housing, draconian immigration laws, and bring Latinx communities closer to environmental justice.

“Half of Latinos live in the most polluted cities in the country, and even more live in one of the three states heavily affected by extreme weather events,” the report notes, “sea-level rise and hurricanes in Florida, heat waves in Texas, and droughts in California.” Not to mention, the devastating effects on Latinx communities of Hurricane Maria, one of the most extreme natural disasters in the United States’ recent memory, which smashed into Puerto Rico in 2017 and killed almost 3,000 people. The halting federal response to the crisis was often criticized as being an example of both logistical problems and racism.

Other Democratic presidential candidates, like Joe Biden, have highlighted how their platforms will support the country’s Latinx population, but Buttigieg is the only one who’s released a plan with this level of specificity. South Bend, Indiana, where Buttigieg is mayor, has a Latinx population of 14 percent, comparable to the 16 percent in the national population.

He plans to invest $10 billion to expand wastewater services, triple EPA funds for water contamination and Superfund site clean up, enact or enforce more rigorous air quality regulations, and establish several Offices of Healthy Equity and Justice across relevant federal agencies, which, the report says, would “oversee programs related to the social determinants of health.”

“We’re impressed that he’s put together a plan that is specifically acknowledging the unique realities and challenges of Latino communities in the US,” says Jennifer Allen Aroz, the founder of Chispa, a branch of the League of Conservation Voters focused specifically on Latinx issues. “And thinking about how to level the playing field and acknowledge the discrimination and systemic inequality and racism that the community faces.”

While Allen Aroz acknowledges that the South Bend mayor’s proposals address issues that are central to remedying environmental problems plaguing Latinx communities, there are others he overlooks, like public transportation and agricultural labor conditions. As for the role those communities play across the country’s farms and fields, “We haven’t heard a commensurate level of concern for the conditions of farm workers, both from exposure to chemicals and pesticides that are applied,” she says. “But also from having jobs that are healthy and treated with dignity.”

Critics have pointed out that for Buttigieg’s proposals to result in meaningful change, he’ll need to address the structural elements of society that created the social inequities his policy proposals are trying to mitigate. And that’s not easy, especially given that Buttigieg has relied on big donors to fuel his presidential campaign, stoking fears among some advocates that if he becomes president, it’ll be those benefactors and their interests that he’s beholden to, not those of the low-income communities or those of color that his white paper purports to help. Like all the Democratic candidates, he has sworn off donations from fossil fuel companies, which are major contributors to air and water pollution. But the policies he’s proposing could potentially still stand in conflict with the interests of other donors.*

Of all the candidates, Buttigieg and Biden have been criticized for large donor events closed to the press and public. “Those doors shouldn’t be closed,” said Massachusetts senator and fellow Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren earlier this month. Subsequently, the Buttigieg campaign has opened its fundraisers to the press, but that hasn’t ended the criticism of his attempts to appeal to wealthy donors who may seek to influence policy.* When the doors to a Buttigieg private donor event in a Napa Valley wine cellar opened, the baroque table settings and Swarovski crystals became an issue during the Democratic presidential debate last Thursday. A particularly heated moment took place between Warren and Buttigieg about that event. As my colleague Tim Murphy wrote:

And that’s when Warren brought up the wine cave. “So, the mayor just recently had a fundraiser that was held in a wine cave, full of crystals, and served $900-a-bottle wine,” she said. “Think about who comes to that.”

“We made the decision many years ago that rich people in smoke-filled rooms would not pick the next president of the United States,” she added. “Billionaires in wine caves should not pick the next president of the United States.”

Buttigieg pushed back, noting (as he has before) that he has the smallest net worth of anyone running. “I’m literally the only person on this stage who is not a millionaire or a billionaire,” he said. By Warren’s logic, Buttigieg continued, Warren herself was part of the problem.

“These are not abstract theoretical concepts,” says Bahram Fazeli, the director of research and policy at Communities for a Better Environment, and environmental activist group that operates in California’s frontline communities. “How much are you willing to stand up to those forces, those historical trends? It takes more than a four-page white paper. You have to invest political capital. It might cost you votes and campaign donations from vested interests who don’t agree with how you’ll transform the regulatory system.”

Environmental justice advocates say that Buttigieg will ultimately need to make a choice between those groups, especially when he continues to shroud information on the identities of his largest donors when disclosing campaign finance information, which Politico recently reported on. “Actions speak louder than plans,” Mustafa Ali, the former head of the EPA environmental justice office, wrote in an email.

Other environmental advocates seem to consider the white paper as nothing more than an attempt to court votes. “I don’t think that we can really call Mayor Pete a climate champion at this time,” says Anthony Rogers-Wright, a policy coordinator at Climate Justice Alliance, a collective of several dozen climate equity groups that exist in communities disproportionately affected by environmental problems. Rogers-Wright cites Buttigieg’s continued acceptance of money from Super PACs—fossil fuel or not—and his stance against an outright fracking ban.

If Buttigieg is authentic about his plans, and El Pueblo Unido/A People United: A New Era for Latinos is the beginning of a sincere effort to address environmental inequities within the communities bearing that burden, Fazeli has a suggestion for the campaign’s next step: “We would encourage Mayor Pete and other presidential candidates to come and visit the communities that are at the front lines and disproportionately affected by the fossil fuel operations.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article referred to donations by Amazon. Amazon cannot contribute directly to any candidate. Additionally, this article has been updated to reflect the Buttigieg campaign policy on allowing press to fundraiser events.