Assistant Energy Secretary for Nuclear Energy Kathryn Huff at a Senate committee hearing.Francis Chung//Politico/AP

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Kathryn Huff grew up in Bellville, Texas, a city of about 4,200 residents in the rural area west of Houston, and discovered at a young age that she had an aptitude for math.

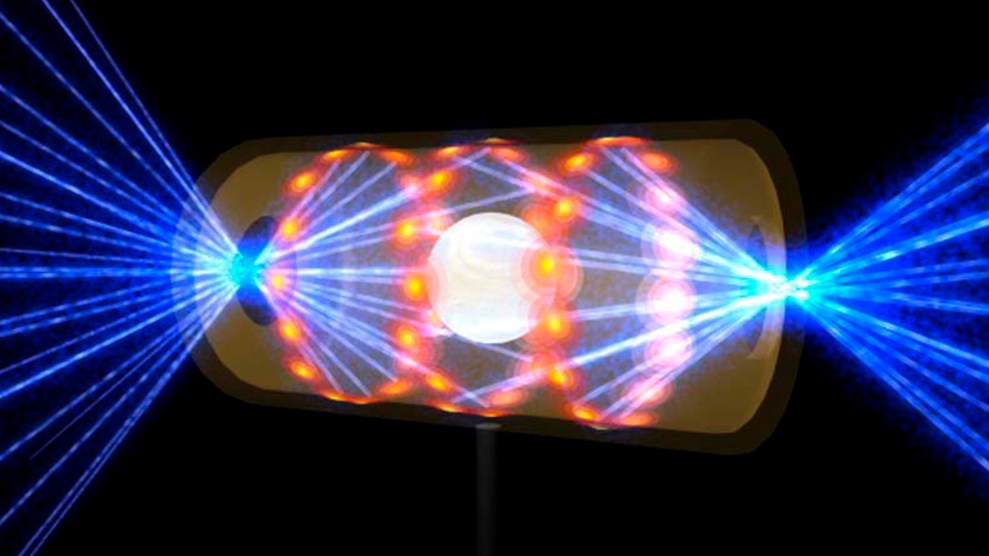

She remembers the moment that she toured the Texas A&M University nuclear research reactor and saw Cherenkov radiation, which gives off a brilliant blue light. “Wow, that’s pretty cool,” she recalls saying.

From there, she took steps toward a life as a nuclear researcher before a recent detour into politics. Following her confirmation by the Senate last year, in an 80-11 vote, she is an assistant secretary at the Department of Energy and head of the Office of Nuclear Energy, one of the top officials in the government working on the development of nuclear power plants.

And she’s 36 years old.

I spoke with Huff about why she’s optimistic about the development of small modular reactors and why it’s imperative that the country develop a new generation of nuclear power plants. The nuclear industry is hoping that SMRs can be built affordably and on schedule, which would be unlike recent experiences with projects like the expansion of the Vogtle plant in Georgia. It’s too early to say whether SMRs will succeed in the market, and there are plenty of people who have doubts. Here is our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

I wanted to start with your path to getting into nuclear power. How’d you get here?

I was a rural Texas child, a child of mechanical engineers, and so, a tinkerer. I had the opportunity to go to a math and science academy instead of the later years of high school, called Texas Academy of Math and Science. I went to the University of Chicago, became a physics major. And it seemed less useful than being a real nuclear engineer. I was worried about climate change and took a class on energy systems and energy economy and the climate. And I thought, “I’ll apply to grad school in physics and nuclear engineering.” And that sealed the deal. I became a nuclear engineering PhD student at the University of Wisconsin. And the rest is history. I became a postdoc at Berkeley, a professor at the University of Illinois. I had no aspirations for a career in government, but someone put my name in the hat, and here I am in this administration, as a political appointee.

I realize in hindsight, that most of my first-hand experience with nuclear power is with plants where the news was almost always bad, including FirstEnergy’s Davis-Besse plant in Ohio, which has had safety issues and high costs. I think that’s affected the way I look at nuclear power.

I think it does depend extremely on one’s personal experience, right? You just described, very self reflectively, how you got to the feelings you have. My parents’ generation were really concerned about the atomic bomb and tightly associated nuclear power with nuclear weapons, and there’s a fundamental flaw there. My generation is profoundly concerned about climate change, and the climate crisis can only be solved with clean energy. Right now our biggest single source of clean electricity in this country is nuclear power. And so a lot of folks in my generation have that as the sort of existential crisis driving their concerns.

Folks who’ve lived near a nuclear power plant sometimes are very fond of nuclear power, because it’s a well-operating plant, which has employed their fathers and friends. And some folks live near a plant that had concerns like you’re describing with Davis-Besse, right? And I think that’s really critical. I think universally most people are concerned about the spent nuclear fuel. Most people will ask about that. And most people also have concerns about safety. But I think that’s pretty straightforward these days to kind of talk about because nuclear power has an incredible safety record.

I think your most recent article touched on the thing that is sort of the last concern of folks who are otherwise convinced, which is the economics and timeliness of construction, which remains challenging for big mega projects, whether it’s a nuclear reactor or an airport.

My goodness, you have a tough job. It’s like, “Just solve how to build this power source that has all these attributes that we really like, but it’s got this really big problem, which is that you build a project and companies go bankrupt, and it takes 10 years to do anything. Fix that.” So walk me through, how do we fix that?

Yeah, so it takes a lot of people, not just me. I’m lucky to have the team, not just in my office, but of course, the rest of the Department of Energy, and our administration, in general, really recognizes the role nuclear can play.

Industry is getting better at learning from their mistakes. We will see Vogtle’s unit three and four turn on this coming year. I’m really pumped about it. And yes, they were expensive and took longer than expected, but still will be an incredibly important, critical part of the baseload energy that’s required to make a high penetration of renewables possible on our grid, right? Significant baseload energy, like the gigawatts that will be provided by those two units, make it so that really large scale-out and build-out of renewables are going to be possible on a grid that’s also stable. And so we can be really proud of that. And yet, I’m impressed that the industry is also taking a moment to reflect on it and do some lessons learned.

As we think about the future in the coming decades, the president has a series of pathways to net zero by 2050 that was published in 2021. And in the context of nuclear, we need to at least keep the same amount of gigawatts of nuclear on the grid in 2050 as we have today. Since some will be shut down between now and then, that means building new reactors. But we may need to get to as much as twice the nuclear capacity as we currently have on the grid depending on how the other renewables and storage pan out in the coming decades.

How do we double the amount of nuclear power on the grid in the coming decades? Well, what it looks like is probably smaller, more modular reactor designs that are built more like airplanes than airports, that leverage construction processes that aren’t stick-built construction on site, but rather are factory assembled, factory regulated devices that can be shipped in parts and components and assembled on site. That should provide some economies of scale. And we really hope that the first of a kind reactor demonstrations that we’re building through cost-shared public-private partnerships with some companies this decade will turn into a wave, an order book, of deployments of those same reactors in the coming decades.

But where will they be built? Well, I think there are a couple of really excellent opportunities for locations. Existing nuclear power reactor sites could potentially be excellent locations for future SMRs. But also retiring and retired coal plant sites have high voltage power lines at the right capacity for a concentrated baseload power system.

We do have one example of this already happening right now through a DOE program, the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program. TerraPower Natrium demonstration is a sodium cooled fast reactor being built by a company called TerraPower, partially funded by Bill Gates. And that sodium-cooled fast reactor is being built in Kemmerer, Wyoming, which is the site of a retired coal plant. So that coal plant is doing this coal-to-nuclear transition that we would really like to see.

How important is it that that project be within shouting distance of its budget and timetable?

It’s critical. And it’s one of three of these demonstrations. One will be the TerraPower project, one will be X-energy’s Xe-100, which is the high-temperature gas reactor and one will be the NuScale VOYGR six pack, a small, modular light water reactor being built in Idaho. And, we do need to see these reactors succeed. But there are other companies also deploying small modular reactors in the coming years. GE Hitachi has a design for a boiling water reactor at 300 megawatts that they intend to build in Canada, for example. Some of these reactors must succeed at building in a predictable timescale on a predictable budget.

How far away are we from that factory approach where there is more of a regular construction cycle?

We can’t wait until 2030 to generate a demand signal for these next reactors. The reactors that are being built now might not connect to the grid until 2030. But in the coming five years, we need to see order books starting to plan for the second, third, fourth, fifth of a kind, because that’s what will spur that company that’s currently building, like, one unit to build a factory that builds units. Getting that order book together is sort of precursor to the thing that will drive even further orders. So it’s going to be a really challenging decade, where we will know that we’re succeeding if five years from now, there are 10 to 20 orders for small modular reactors on the books in contracts between utilities and vendors.