<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/dklimke/2797228335/in/photostream/">Dan Klimke</a>/Flickr

Like Kiera—and, I’m sure, many of the readers of her article—I was a bit shocked when I calculated how much I spend on food. I like to think I’m thrifty in my food spending habits—I cook a lot and usually eat out only on the weekends—but I don’t usually add up my food costs and rarely make serious estimates for food spending when I make a budget, instead assuming that I’ll manage to make do with whatever’s left after I cut a check for rent, buy a bus pass, and pay my utility bills.

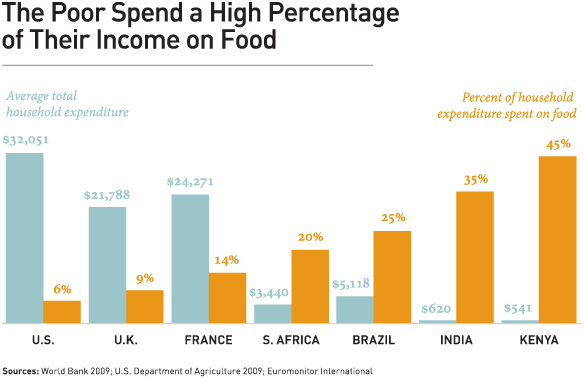

Of course, this kind of logic is completely insane to most people in the world, for the simple and obvious fact that food is the most important thing to budget for. It’s only because I live in a rich country where having enough to eat isn’t really an issue that I can be so clueless about my food spending habits; as demonstrated by the chart below, the higher a country’s average income, the smaller the percentage of income spent on food.

On some level, this is pretty intuitive—food is a basic need, and there’s only so much you can eat, no matter how much money you have. But even among developed countries, our food spending is ultra-low: People in most European countries spend over 10 percent of their incomes on food. In fact, Americans spend less on food than people in any other country in the world. Even we Americans didn’t always expect our food to be so cheap, though: Back in 1963, when Molly Orshansky, an employee of the Social Security Administration, created the nation’s first poverty threshold, she simply tripled the cost of the FDA’s “thrifty” food plan, since at the time most families spent about a third of their incomes on food. So how’d we end up spending just a fraction of that four decades later?

To find the answer, we have to go back four decades to the 1970s, when rising food prices and technological developments led to a host of transformative changes in the US food system whose effects still determine the way many Americans eat. In response to rising food costs and growing demand amongst the expanding middle class, Nixon’s secretary of agriculture, Earl Butz, turned the country’s agricultural subsidy program—originally instituted to help stabilize food supply and farmers’ incomes after the volatility of the Great Depression—into a support mechanism for the industrial production of corn and soy. Butz’s policy of “get big or get out”—made possible by advancements in industrial food production, including technological developments and an abundance of cheap fossil fuels used to make fertilizer and pesticides—encouraged the consolidation of small farmers’ plots into gigantic holdings and led to the rise of agribusiness in place of the family farm.

The changes Butz wrought are visible in our food supply, too: The amount of corn produced each year in America has tripled since 1970, from 4 billion bushels then to more than 12 billion today. Faced with an abundance of cheap corn, the food industry figured out how to make it into cheap meat, milk, eggs, and sweets. Over time, the cost of things made from highly-subsidized crops like corn, wheat, and soy—things like cheeseburgers and soda—has declined drastically. While you can debate the merits of local, organic, and seasonal food, and question what it means to eat sustainably, the dominant food production policy in the US is oriented around just one metric: producing calories as cheaply as possible. We’ve gotten so good at producing calories efficiently, in fact, that our problem is no longer that we can’t afford enough food—it’s that the types of calories that are least expensive are the ones that are worst for us.

There are obvious reasons why spending less on food is a good thing—namely, that not having to worry about survival on a daily basis is a pretty basic development goal that we’ve nonetheless only recently managed to achieve. BUT there are also some less obvious reasons why it’s not so great. As Michael Pollan, Marion Nestle, and others who study our food system have pointed out, food is as cheap as it is because the true costs have been externalized—that is, we pay for them in rising obesity rates, environmental degradation, lax safety measures, and disgraceful labor practices. And if you count the money taxpayers send Big Ag in subsidies—around $261.9 billion between 1995 and 2010—cheap food starts to seem like it might not be such a bargain after all.

Still, it’s not impossible to buy and prepare good food even on a tight budget. Seeking to bust the myth that fast food is cheaper than cooking, Mark Bittman has argued that making a meal of roast chicken, salad, and vegetables costs about half as much as buying a family of four dinner at McDonald’s, and while Tom Philpott points out that cooking at home requires unpaid labor, making a “fuss-free meal” one that’s hard to refuse, he notes that cooking can be enjoyable work once you know what you’re doing. (For more on how to eat well without going broke or burning out, see Kiera’s interview with the chef and author Tamar Adler.) And even eating out a lot isn’t necessarily a bad thing—spending money at locally-owned restaurants is a great way to put money back into your community. (Though of course it’s harder to find out where your food comes from when you go out to eat without turning into a Portlandia sketch.)

It should be clear by now that whether we’re talking about iPhones, anthropomorphic stuffed bacon toys, or actual bacon, expecting to get more for less comes at a cost. I’m not suggesting we should take as our model the days when people spent fully a third of their incomes on food; making food more expensive makes it harder for poor—and middle class—people to afford. But I do think it’s worth reevaluating our spending priorities, and wondering why we’re so reluctant to pay a bit more for something so essential. The big question is how we can value food more without turning healthy food into a luxury item or making people who are already struggling to pay their bills worse off.