A farmer in Tanzania, where land and water grabs are frequent. <a href=http://www.flickr.com/photos/africa-renewal/5101961649/in/photostream>World Bank/Scott Wallace</a> Flickr

In 2010, a former Wall Street trader flew into war-torn Sudan to negotiate a deal with a thuggish general. He had his eye on a 1 million acre tract of fertile land fed by a tributary of the Nile in the southern section of the country, a region that later claimed its independence as South Sudan. The investor, who planned to profit by developing and exporting agricultural commodities, boasted about how the region’s instability was a principal variable in his financial model: “This is Africa,” he told reporter McKenzie Funk, who shadowed him for a riveting piece in Rolling Stone (PDF). “The whole place is like one big mafia. I’m like a mafia head.”

Over the last decade (and especially during the last four years) wealthy nations have increasingly brokered deals for huge swathes of agricultural land at bargain prices in developing countries, installed industrial-scale farms, and exported the resulting bounty for profit. According to the anti-hunger group Oxfam International, more than 60 percent of these “land grabs” occur in regions with serious hunger problems. Two-thirds of the investors plan to ship all the commodities they produce out of the country to the global market. And droughts, spikes in food and oil prices, and a growing global population have only made the quest for arable land more urgent, and the investments that much more alluring.

In what a recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) characterizes as a “new form of colonialism,” investors from the US, UK, and China are gobbling up foreign farmland at “alarming rates” and often with little consultation and compensation of poor small-scale farmers and local populations.

According to the PNAS study, the land grabbing phenomenon has already claimed some 203 million acres, or about .7 to 1.75 percent of the world’s total farmland, since 2002, with the majority of acquisitions after 2008. Out of 41 land grabbing speculators, the US ranks second, with 9.14 million acres grabbed, an area larger than the country of Qatar. And according to another report from the Oakland Institute, highlighted by my colleague Jaeah Lee, many of the purchases are carried out by private equity funds, university endowments, pension funds, and hedge funds looking to strengthen their portfolios by capitalizing on declining natural resources. And as Mother Jones blogger Tom Philpott has noted, the grabbers have an average per capita GDP about five times the size of the grabbed.

Take a look at the top five land-grabbing countries below and their respective claims:

Data source:”Global land and water grabbing.”

Data within the PNAS report also indicate that the “mafia head” approach of targeting vulnerable countries for investments is not just the strategy of a lone land-grabbing cowboy, but standard practice. It’s easier to wrest land and displace small-scale farmers in countries with a weak rule of law, according to Oxfam. In many cases, the land is developed to export crops or commodities for biofuels, and in other cases, left to sit idle so it can increase in value before it’s sold.

Of the countries that lost the highest percentages of their cultivated land, nine out of 10 have malnourishment rates of 5 percent or more (see chart below). And according to Foreign Policy and Fund for Peace’s Failed States Index, all the states in the graph below, with the exception of Uruguay, are categorized as unstable.

Data source:”Global land and water grabbing.”

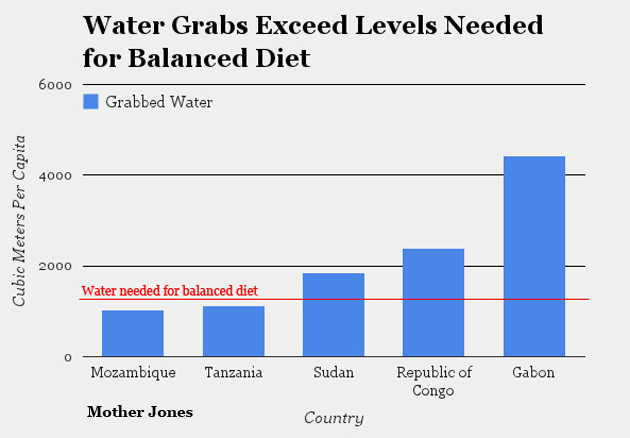

Given that 86 percent of the world’s water resources flow into agricultural production, the grabs also hijack a good portion of rainwater and irrigation water. The graph below shows that the top five annual per capita water grabs exceed or come very close to the amount of water needed for a balanced diet for that country’s citizens.

Data source:”Global land and water grabbing.”

In October of 2012, Oxfam called on the World Bank to freeze its agricultural investments in land in order to review its policies and develop stronger guidelines on how to avoid land grabs. According to Oxfam, the World Bank’s projects have been cited in 21 formal land rights complaints since 2008 by communities from Asia to Africa.

But the World Bank rejected the suggestion, saying that it would “do nothing to help reduce the instances of abusive practices and would likely deter responsible investors willing to apply our high standards.” It acknowledged, however, that enforcing those standards “is challenging.” It’s a challenge that must be overcome, or land grabbing, as Oxfam says, could become “one of the great scandals of the 21st century.”