In a major address at Knox College in Galesburg, Ill., last week, President Barack Obama launched a push to “deliver on behalf of those people that are still struggling” in this recovering economy. Some of his priorities include investing in green jobs, focusing on education and training, and raising the minimum wage. On Monday, in what will likely be the largest fast-food strike in US history, workers in seven cities are lending him a hand in the effort by walking off the job to demand higher wages.

Thousands of fast-food workers in New York City, Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City and Flint, Mich., will strike at joints like McDonald’s and Wendy’s, calling for a wage increase to $15 an hour and the right to join a union without retaliation. (Although all American workers are legally allowed to join unions, many who try to organize are fired or punished with reduced hours.)

Many fast-food workers are paid at, or just above, the minimum wage. The federal minimum wage is $7.25, though it’s higher in 18 states and the District of Columbia. Fast-food wages have fallen 36 cents an hour since 2010, even as the industry has raked in record profits.

This is part of an economy-wide problem; the bottom 20 percent of American workers—some 28 million employees—earn less than $9.89 an hour, or $20,570 a year for a full-time employee. Their income fell five percent between 2006 and 2012. Meanwhile, average pay for chief executives at the country’s top corporations leaped 16 percent last year, averaging $15.1 million, the New York Times reports.

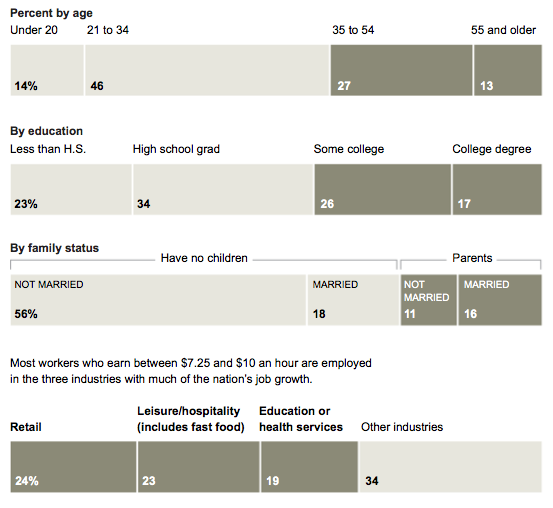

The Times has a great chart showing what low-wage America looks like. Here are the demographics of the 21 million workers who make between $7.25 and $10 an hour:

The mobilization of fast-food workers is a pretty new thing, because the industry has traditionally had high turnover. But the slow economic recovery, which has been characterized by growth in mostly low-wage service sector jobs, has resulted in a growing population of adult fast-food workers who can’t find other work.

Fast-food workers can work in the industry for years without more than a dollar or two raise. In his story on the strikes at Salon Monday, Josh Eidelson points to a recent study by the National Employment Law Project that explains why: “Opportunities for advancement in the fast food industry are significantly limited compared to other industries,” the report says. “[O]nly 2.2 percent of jobs in the fast food industry are managerial, professional, or technical occupations, compared with 31 percent of jobs in the overall US economy.”

The strikes today follow waves of fast-food worker strikes across the country this past spring and last fall. And they are part of a string of recent strikes in other industries too. In recent weeks, federally-contracted workers in Washington walked off their jobs; and there has been growing worker discontent at Walmart over the past year.

As City University of New York labor expert Ruth Milkman told Eidelson of the Monday strikes, “As a consciousness-raising strategy for the United States, it’s really great.”