A rice farmer in Mali, one of 19 Feed the Future "focus countries" around the world. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/feedthefuture/"> Feed the Future</a>/Flickr

Ending hunger for millions of people by boosting food production worldwide has long been a priority of the Obama administration, advanced through its $7 billion Feed the Future initiative. Yet according to a new report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), it’s not clear if Feed the Future is working as intended, or if its funds are falling through the cracks.

The idea behind Feed the Future, a multi-agency initiative led by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), is to link agribusiness with governments in poor countries to grow more food for local consumption and export. Currently, are 19 Feed the Future “focus countries,” selected both for their high rates of starvation and for their potential for attracting agribusiness investment. These include Senegal and Tanzania (two stops on Obama’s African tour this summer), Ethiopia (where USAID recently partnered with PepsiCo to train farmers to grow chickpeas for Sabra Hummus), Cambodia, Haiti, and Guatemala.

While the US government determines the final dispensation of Feed the Future funding, host-country governments also weigh in on how they’d like the aid dollars to be spent. This “country-led approach” is nothing new. Academics and aid organizations widely believe that host governments must play a leading role in development projects for them to succeed. As Paul Weisenfeld, an assistant to USAID administrator Rajiv Shah, put it recently, “Acknowledging that development is no longer about top-down, donor-driven programs, Feed the Future supports countries as they pursue the priorities they’ve set for their own agricultural development.”

Yet, according to the GAO, host governments often have little time to draw up their investment plans, and USAID staff often hold consultation sessions in capital cities, not the rural areas where agricultural investment would be directed. The GAO also found that USAID has failed to require its people on the ground to account for some of the biggest risks associated with making foreign governments partners in the development process. The watchdog agency outlined what could go wrong in a 2010 report issued when Feed the Future still had the sheen of a new program. Many partner governments, particularly in Africa, the GAO reported, simply didn’t have the personnel to incorporate a large influx of aid into their development agendas. Moreover, countries suffering from intellectual brain drains would struggle to sustain high-technology farming and infrastructure projects without foreign support.

In its most recent report, the GAO noted that Washington-based USAID staff had improved their risk-assessment process since 2010 by developing a “scorecard” which tracks improvements in the investment climate in each of the focus countries. But the larger problem is that USAID staff overseeing those countries are not required to document the risk or find ways to mitigate them. Twelve out of 19 country plans, the GAO said, did not specifically discuss risks with the “country-led approach” to Feed the Future aid in that country.

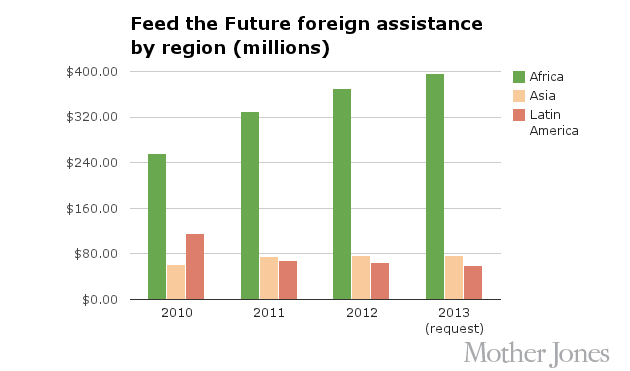

That’s a big problem considering where the money is going. Among academics who study foreign development, one commonly used index of political and economic stability is the Fund for Peace’s Failed State Index. Scores are tallied out of a possible 120 points, with higher numbers indicating less stability. Feed the Future’s 19 focus countries scored an average of 88.5 points in 2013—an improvement of less than one point since 2009. The initiative’s 12 African partners have fared worse. Since 2009, these countries’ stability scores have increased an average of two points. Yet allocations for Feed the Future have increased year after year, with the money disproportionately favoring African recipients.

Political instability could increase as additional burdens on recipient countries mount. As the GAO reported in 2010, “high population growth rates, erratic weather patterns that could worsen with climate change, and natural disasters further strain the capacity of [focus countries’] governments to respond to numerous demands on limited resources.”

Whatever its potential shortcomings as an anti-hunger initiative, Feed the Future may be about creating opportunities for agribusiness as much as it’s about ending hunger, anyway. About half of the staff GAO surveyed at USAID and other agencies reported that they had provided “technical assistance or research data to the for-profit sector.” But the danger of providing huge aid packages to governments unable to handle them is not just creating waste, but dependence. Despite rising GDPs across Africa, aid dependence is still a huge problem. Far from making Feed the Future’s focus countries more independent, by pursuing a master plan backed with massive aid dollars without the partners on the ground to handle it, USAID could further exacerbate dependence on foreign money and expertise.

Feed the Future’s advocates in Washington may need a reality check about the initiative, but without ongoing assessments of risks on the ground, GAO warns, American money, goodwill, and expertise could be squandered.