<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/starr-environmental/9219693374/in/photolist-f3ta3v-f3t9At-f3Hk8Y-f3taGz-f3HkCA-f3t9aD-f3HgyJ"> Forest and Kim Starr </a>/Flickr

Imagine if Monsanto announced the debut of a genetically engineered superfood—a vegetable rich in protein and essential vitamins and minerals, perfectly adapted to Africa’s soils and changing climate.

There’d be howls of protest, no doubt, from anti-GMO activists. But also great adulation—possibly a World Food Prize—along with stern lectures about how anti-science romanticism must not impede heroic corporate efforts to “feed the world.”

Thing is, such superfoods exist in Africa. They exist thanks not to the genius and beneficence of a foreign company, but rather through millennia of interactions between Africa’s farmers and its landscape. And while their popularity waned in recent decades as urbanization has swept through the continent, they’re gaining renewed interest from food-security experts and urban dwellers alike, reports a new article by Rachel Cernansky in Nature.

Cernansky focuses on the work of Mary Abukutsa-Onyango, a horticulturalist at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology in Kenya, who has since the 1990s been a kind of Johnny Appleseed for reviving appetites for indigenous vegetables in Africa. Here’s Cernansky:

Most of the indigenous vegetables being studied in East Africa are leafy greens, almost all deep green in colour and often fairly bitter. Kenyans especially love African nightshade and amaranth leaves (Amaranthus sp.). Spider plant (Cleome gynandra), one of Abukutsa’s favourites for its sour taste, grows wild in East Africa as well as South Asia. Jute mallow has a texture that people love or hate. It turns slimy when cooked — much like okra. … [M]oringa (Moringa oleifera) is not only one of the most healthful of the indigenous vegetables — both nutritionally and medicinally — but it is also common in many countries around the world.

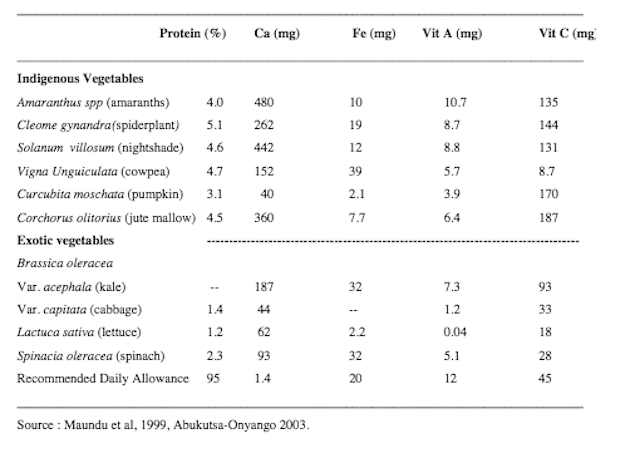

In a 2010 paper, Abukutsa-Onyango demonstrated the nutritional punch packed by these foodstuffs. This chart, pulled from the paper, shows how African vegetables like the leaves of amaranth, pumpkin, and cowpea (black-eyed pea) plants outshine rival western greens that have been introduced into African agriculture over the past century.

Then there’s the leaves of the moringa tree, native to Africa and parts of Asia, which, according to the anti-hunger nonprofit Trees for Life International, deliver three times more vitamin A than carrots, seven times more vitamin C than oranges, and twice the protein of cow’s milk, per 100 grams.

Unlike “exotic” (i.e., non-native to Africa) vegetables like kale and cabbage, these crops are adapted to Africa’s soils and growing conditions. “Most of the traditional varieties are ready for harvest much faster than non-native crops, so they could be promising options if the rainy seasons become more erratic—one of the predicted outcomes of global warming,” Cernansky writes.

As a result of these advantages, indigenous vegetables are gaining traction throughout East Africa. Traditional markets, supermarkets, and restaurant menus in Nairobi feature them heavily, Cernansky reports. As a result, “Kenyan farmers increased the area planted with such greens by 25 percent between 2011 and 2013.” They’re also gaining ground in Western Africa.

Of course, spiderplant and cowpea leaves are a long way from solving Africa’s nutritional problems. As of 2013, indigenous vegetables accounted for just 6 percent of Kenya’s total vegetable market, reports SciDevNet. Despite growing demand, SciDevNet found, production is constrained by the same factors that haunt African food security broadly: poor infrastructure (roads, rail, etc.) for bringing fresh food from farm to market, along with a dearth of investment in research and development.

There are no simple answers, no silver bullets, to the problem of ensuring a robust food supply on a warming planet with a growing population. But it’s important to remember that the best, cheapest solutions aren’t necessarily the ones that emerge from patent-seeking laboratories.