<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/48063283@N07/4420214662/">BigBeaks/Flickr</a>

After reading my post on Thursday about the depredations of the credit and debit card industry, Matt Yglesias objects to my plan to “micro-manage” their business:

Regulate business to prevent negative environmental externalities, sure. Basic safety, okay. But the idea that what we need is for a bunch of people to get together and say that it would be better to ban this and that and the other capitalist act between consenting adults just strikes me as the wrong way of going about things. Purely economic regulation of this sort doesn’t have a compelling track record, runs into all kinds of Hayek-esque knowledge problems, and is basically an open invitation down the road for regulatory capture and the use of rules to prevent the emergence of competition. Count me out.

This is a very good point, and it’s one that normally I’d find persuasive. So much so, in fact, that I originally planned to address it in my initial post. But that post ended up running too long as it was, so I decided to leave it for another time. Which this is. So let me take a crack at persuading Matt and other doubters that although there are indeed some important issues here related to consenting adults, competition, and Hayek-esque knowledge, they mostly point in a non-intuitive direction. There’s a lot less micromanagement here than meets the eye.

Here’s the thing: in my initial post I actually proposed only two pieces of government action: one to regulate interchange fees (the 1-2% fees that merchants are required to pay card issuers on every debit or credit transaction) and another to regulate overdraft fees. Let’s take a look at those

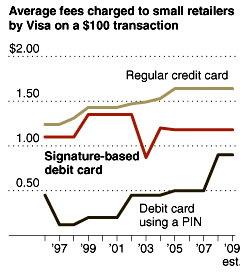

First, interchange fees. The problem here is twofold: (a) the fees themselves are non-transparent to consumers and (b) they’re administered by an effective monopoly. There are lots of banks and credit unions that issue credit and debit cards, but two companies — Visa and MasterCard — control the vast bulk of the payment network and set the interchange fees. Even the most ardent free marketers usually concede that a combination of monopoly power and opaque pricing is a problem, and that’s what we have here.

So let’s try a thought experiment. What if credit and debit cards lived in a real free market with transparent pricing? Suppose that instead of just two payment networks there were a dozen. And suppose that instead of hiding interchange fees by extracting them from merchants, who pass them along to consumers invisibly, the card companies actually charged consumers directly. What would happen?

Answer: banks and payment networks would compete for customers’ business, and they’d largely do this by trying to offer the most efficient, lowest-cost service. After all, if consumers actually saw the interchange fee tacked onto their bill each month, they’d gravitate toward banks and payment networks with the lowest fees. Those fees would very quickly converge  on an amount just slightly over the actual cost of running the network, and given what we know about that from the early days of debit card networks before Visa and MasterCard took over (you can read the astonishing story here), that means fees would be about a quarter of what they are now.

on an amount just slightly over the actual cost of running the network, and given what we know about that from the early days of debit card networks before Visa and MasterCard took over (you can read the astonishing story here), that means fees would be about a quarter of what they are now.

Now, would some card issuers try to compete on other factors? Maybe. American Express charges an annual fee and lots of customers consider it a good value anyway. So maybe some banks and one or two of the payment networks would charge a higher interchange fee and then offer rewards cards to customers to make it worth their while. This sounds like a pretty improbable business model to me — would you knowingly pay a higher monthly fee in order to get a fraction of it back in rewards? — but you never know. And if it works, I’m fine with it. That’s the free market at work. A real free market with competition and transparent price signals.

Unfortunately, as economists since Adam Smith have pointed out, most of our rock-jawed titans of industry don’t really like free markets. They much prefer cozy cartels and opaque pricing, which are far more profitable. So although I’d be fine with regulations that forced a genuine free market onto the card industry, I’m not sure it’s feasible. As a next-best alternative, then, I favor federal regulations that push down interchange fees to something within shouting distance of what they’d be in a free market.

Second, overdraft fees. The problem here is simpler: overdraft protection is, by any common sense definition, a short-term loan. And it should be regulated as a short-term loan. Unfortunately, back in 2004 the banking industry strong-armed the Greenspan-era Fed into declaring that up is down and black is white. The Fed conceded, in its final report on the matter, that banks promote overdraft protection “in a manner that leads consumers to believe that it is a line of credit.” And the Fed politely encouraged them to be a little more honest about this. But that was it. Officially, overdraft charges still weren’t loan payments, they were fees, and banks could charge whatever they wanted.

There are a couple of problems here. The first is that regardless of the Fed’s Alice-in-Wonderland opinion, overdrafts really are loans and ought to be regulated as loans. This is, obviously, an intrusion on a pure free market, but it’s not much of one: regulating consumer loans is a long-accepted role for the federal government, and regulating overdraft fees fits right into this role. All we need are rules for overdraft fees that are roughly the same as for any other consumer loans. That includes limits on interest rates, transparency about what’s being charged, and restrictions on the fees and charges that surround the origination of the loan.

Beyond that, though, there’s also a pure free market distortion in the way overdraft protection works today. In a proper free market, consumers have a choice. If they don’t want your good or your service, they can choose not to buy it. But until recently, that wasn’t the case: consumers weren’t notified that they were about to overdraw their account. They weren’t given the option of choosing to accept or decline the purchase anyway. Hell, they weren’t even given the option of not having overdraft protection in the first place. On the contrary, overdraft protection was deliberately set up to rope low-income consumers into paying wildly abusive fees for small mistakes. What kind of free market is that?

So that’s my case. In the case of interchange fees, the free market has been so badly distorted that it simply doesn’t work in any recognizable way. There are two options to fix this: either force transparency and competition on the industry or else regulate fees down to levels that aren’t too flagrantly abusive. I suspect that the latter is, at this point, the only feasible option. [Update: And the latter is, at least partly, going to get done. Three cheers for Sen. Dick Durbin.]

In the case of overdraft fees, simply regulate them as short-term loans with a maximum interest rate of, say, 100%. It’s an intrusion on the free market, but it’s a small and long-accepted one. As a rich member of a rich society, I have a hard time accepting that we aren’t willing to impose this kind of modest regulation in order to rein in a genuinely contemptible practice that’s cynically set up to prey on the weakest, poorest, and most unsophisticated consumers as a way of subsidizing finance for the best off among us.

And one final thing. You can, as some pious conservatives say, avoid both interchange fees and overdraft fees simply by not using credit or debit cards. If you don’t like the way the industry works, exercise your right in a free market not to participate. And 20 years ago that was a perfectly good option. But in practical terms, it just isn’t anymore: it’s close to impossible to live an ordinary working class or middle class lifestyle without credit and debit cards, and it’s only going to get even more impossible as time goes on. For better or worse, credit and debit cards are now required parts of our existence, and that means consumers need to have real choices and real competition within the e-payment network we all live in. And that’s what I want: choice and transparency, with modest regulation to prevent abuse of the most vulnerable among us. Fifty years ago that wouldn’t have been controversial. It still shouldn’t be.

POSTSCRIPT: Just to address a couple of likely questions before they come up:

First: So how will banks make money on credit and debit cards? Answer: interchange fees would still offset the cost of actually running the payment network. Beyond that they’ll charge annual fees and make money on interest from outstanding balances. You say you don’t like annual fees? Well, you’re already paying one, and it’s a lot bigger than you think. The only difference between interchange fees and an old-fashioned annual fee and is that an annual fee is usually smaller and is always transparent.

Second: what does this have to with financial reform? Answer: nothing much. These fees weren’t directly responsible for the credit bubble or the collapse of 2008, and fixing them won’t do much to prevent future disasters. It’s just the right thing to do for other reasons.

Home page image: BigBeaks/Flickr