Last week, Evan Soltas wrote a column that basically told liberals to give up on unions. “Unions can no longer solve labor’s woes,” he wrote. “That’s not terrible, because the way unions gave workers power created its own problems.”

In response to criticism from Michael Wasser, he wrote this:

The heart of the matter, it seems to me, is whether union decline is basically irreversible…If the decline is permanent…Wasser’s claim about uniqueness has no independent policy implications—it’s merely a statement of pessimism.

Yet I still find that pessimism implausible if one considers this graph (via Jared Bernstein) showing the broad increase in wages in the 1990s. Why? Unionization was also low then. How did wages rise so quickly, then, for the bottom half of the wage distribution? You can thank full employment.

Unfortunately, I agree with Soltas: The decline of union power is irreversible. Private-sector unions are all but dead, and public-sector unions are barely hanging on by their fingernails. That doesn’t mean liberals should give up on labor, or that labor should give up on organizing new industries. Of course they shouldn’t. It just means that as a broad-based force that provides a countervailing force against  the power of the business community, labor’s day is over. Like it or not, liberals have to figure out something else to play that role.

the power of the business community, labor’s day is over. Like it or not, liberals have to figure out something else to play that role.

This is where I depart a bit from both Soltas and Wasser—in emphasis if not in detail. Their focus is primarily on what unions do specifically in the workplace: balancing power between employers and workers and providing a voice for workers that management can hear. Both of those are important, and both are problematic: You can reasonably argue about whether they’re a net positive, or whether unions are the only way of obtaining them. But I view the primary strength of unions differently: They’re a broad-based force that represents the interests of the middle class in the American political arena. Here’s how I put it a couple of years ago after a quick review of the ways in which the past three decades have been disastrous for American workers:

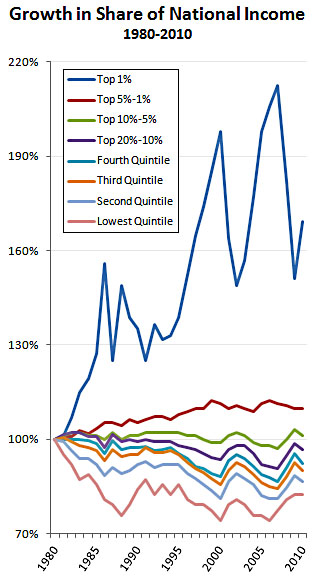

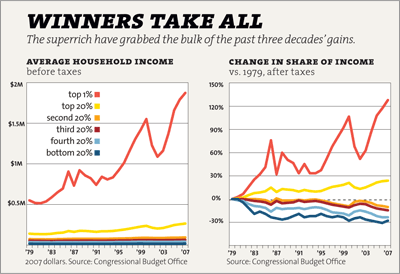

This didn’t all happen thanks to a sinister 30-year plan hatched in a smoke-filled room, and it can’t be reined in merely by exposing it to the light. It’s a story about power. It’s about the loss of a countervailing power robust enough to stand up to the influence of business interests and the rich on equal terms. With that gone, the response to every new crisis and every new change in the economic landscape has inevitably pointed in the same direction. And after three decades, the cumulative effect of all those individual responses is an economy focused almost exclusively on the demands of business and finance. In theory, that’s supposed to produce rapid economic growth that serves us all, and 30 years of free-market evangelism have convinced nearly everyone—even middle-class voters who keep getting the short end of the economic stick—that the policy preferences of the business community are good for everyone. But in practice, the benefits have gone almost entirely to the very wealthy.

…The heart and soul of liberalism is economic egalitarianism. Without it, Wall Street will continue to extract ever vaster sums from the American economy, the middle class will continue to stagnate, and the left will continue to lack the powerful political and cultural energy necessary for a sustained period of liberal reform. For this to change, America needs a countervailing power as big, crude, and uncompromising as organized labor used to be.

And that is a statement of pessimism, because no one on the left seems to have any serious ideas about what this countervailing power might be now that labor is a shadow of its former self. Organized labor really is unique, as Wasser suggests, and for all its problems, that’s why I mourn its decline. There’s no longer any serious countervailing power against the interests of business interests and the finance community, and we’re paying a high price for that.

The decline of labor is simply a fact at this point, and there’s not much point in sticking our heads in the sand and pretending we can turn this around in any serious, sustained way. Liberals should continue to support the cause of labor whenever and wherever we can, but we should also understand that our most urgent task is figuring out how to replace what they used to do. That’s not something we’ve made much progress on.