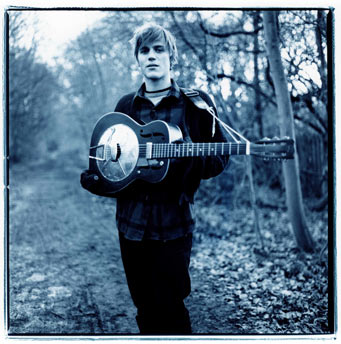

Photo by Steve Gullick

On a balmy Thursday afternoon shortly before Halloween, 27-year-old Johnny Flynn is barreling down I-85 toward Atlanta in a rented Toyota Sienna minivan, along with his opening act, Cheyenne Marie Mizie, and “the help” (a.k.a. his nephew, Sam). Three people, seven seats—it’s like a spaceship, actually, he says. He’s speaking to me on the hands-free. That’s totally dangerous, I tell him. “Is it?” he replies. “Oh. Shit.”

Flynn had better keep moving. A rising star in the British hipster-folk scene, where he regularly appears alongside established names like Mumford and Sons and Laura Marling, the singer is still largely undiscovered on this side of the pond. He’s got a baby due in March with his longtime girlfriend, so he’s cramming in 40 more shows before Christmas—before the reality of late-night feedings begins to dawn.

Flynn and his band, the Sussex Wit, already toured America once in the wake of their brilliant 2008 debut, A Larum (that’s Shakespearean English for “alarm”). They shared a bus with two other groups, sleeping through much of the scenery on account of excessive revelry. This time, Flynn is flying solo and reveling in the proverbial amber waves of grain he’s witnessing from the driver’s seat. “I’m really into it,” he says. Yesterday, cutting across the Appalachians en route to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Flynn saw his first wild bear. “It really blew my mind,” he says.

Flynn has been blowing a few minds himself. His music has been praised by outlets from Rolling Stone to Playboy to Mojo—the other Mojo, in England—and for good reason. Born in South Africa to a family of professional actors and amateur singers, he is a collector of life’s impressions, processing human experience—his and others’—into deceptively complex, deeply soulful songs that overflow with metaphor and poetic narrative.

poetic narrative.

Which is all merely a fancy way of saying that he’s outstanding. Between his first album, 2009’s Sweet William EP, and his excellent new full-length, Been Listening, my own iPod has received quite a workout. Far from the predictably self-indulgent fare of open-mic regulars gone pro, Flynn’s songs are infused with a timeless quality that older songwriters struggle for a lifetime to achieve. “My singular story doesn’t actually relate to anyone else,” Flynn explains, “and it’s not healthy for me either.”

Part of the appeal, beyond the beauty and lush instrumentation of his creations—the lineup includes cello, bass, drums, keyboard, and backing vocals in addition to Flynn’s multiple instruments (more on that later)—is that his words leave ample room for interpretation. They might involve a man living in a box by the tracks (“The Box“), the Siddhartha-like experiences of a young wanderer (“Sweet William,” parts 1 and 2), or a moment of youthful realization (“Kentucky Pill“), but the images they evoke will depend on who’s listening.

Despite the video, for instance, you might not quite know what to make of “Barnacled Warship” or “Water,” a new duet with Marling, but both are pleasures to the ear. “In my mind,” Flynn says, “there’s usually a fairly definitive kind of narrative when I write. But I don’t want to enforce that on other people. I think that’s why I like using metaphor so much.”

He writes his words and music separately, carrying a notebook wherever he goes to jot down thoughts and impressions. “I actually do bits of my writing in sort of incidental spaces—when I’m traveling on the tube, or on a bus,” Flynn says. “More often than not it’s a reaction to how you feel about something, and if you’re sitting down and concentrating on I must write something, then you can’t have a truthful reaction. You’re just guessing at what you would feel in the situation.”

Flynn is fourth of five siblings—he has two older half brothers and an older half sister from his dad’s first marriage, and a younger sister, Lillie, who sings with the Sussex Wit. “We sang a lot in the car together,” Flynn recalls. “My dad sang all the time, and I think we kind of picked it up from him.”

He was born in Johannesberg and at age three moved with his family to Hampshire, England—”an idyllic small place with a river running through it.” They’d fled South Africa shortly after his mother’s cousin and her husband, a mixed-race couple campaigning for the African National Congress, were shot dead by apartheid supporters. (Mixed marriages were illegal then, and the regime had designated Nelson Mandela’s ANC a terrorist organization.)

On stage, Flynn sticks largely to his resonator guitar, but fiddle was his first instrument. Even now, when writing new melody lines, he “has to think about it in violin language.” He took lessons from age six, and when he was eight, his teacher suggested he apply for a music scholarship at a junior school run by the prestigious Winchester College. “I was probably the laziest of the music scholars,” he told me. “I never practiced as hard as the others.” Not so lazy, really: Beyond his specialties—violin, trumpet, and voice—he taught himself guitar, mandolin, banjo, piano, and other instruments that he weaves into his recordings.

When he was 14, the family relocated to rural West Wales to run a bed and breakfast. He started writing and recording his own songs at age 16, playing and singing first into one cassette player, and then playing along with it into a second deck—back and forth like that. After graduating from high school (another music scholarship), Flynn took a year off to travel and work on a fishing boat called The Carolina. He then moved to London to attend drama school, following in the footsteps of his older siblings and his father—a respected actor who starred in many a stage musical and played Ivanhoe in the 1970 BBC miniseries. (As a kid, Johnny did lots of voice work, playing characters on children’s story tapes and the like.)

Playing a bit part on Holby CityHe ultimately spent a year touring with a Shakespeare company, and dabbled in television and film. I was surprised to come across a photo of a photo of Flynn, alert and conscious mid-heart surgery—his chest spread open with a bloody surgical device. I was all set to ask how his heart condition had affected his musical path when he told me the photo was from his bit part as an overdose victim in BBC One’s Holby City, “the British version of ER.” (The gory chest was a prosthetic.)

Playing a bit part on Holby CityHe ultimately spent a year touring with a Shakespeare company, and dabbled in television and film. I was surprised to come across a photo of a photo of Flynn, alert and conscious mid-heart surgery—his chest spread open with a bloody surgical device. I was all set to ask how his heart condition had affected his musical path when he told me the photo was from his bit part as an overdose victim in BBC One’s Holby City, “the British version of ER.” (The gory chest was a prosthetic.)

He also appeared in a movie called Crusade in Jeans, which “sounds like a gay ’80s porn flick,” Flynn admits. “I wouldn’t encourage anyone to see it.” He redeemed himself somewhat, though, by composing the score for an upcoming feature film called A Bag of Hammers. It has nothing to do with crusades, or jeans, and he’s honored to be associated with this one.

Okay, so maybe the acting career hasn’t quite worked out, but this music thing really seems to be the ticket. I ask Flynn whether he feels like he’s on the cusp of something big. “I don’t really see this as an A to B and there’s a place you’ve got to get to,” he replies. “This is like a deepening experience for me, traveling and making music, and whether it’s in front of 10 people or 10,000 people, it’s really rewarding.”

So what, then, is he looking for, if not to be the next Bright Eyes or Billy Bragg or whomever? “I’d really love to break even and get by and pay our rent, because at the moment I’m touring solo because we can’t afford for the band to be out here,” he says. “Last time we toured America, the record label pulled the tour support right before we left, and we said, aw fuck it, we’d go anyway. And we ended up in tens of thousands of pounds of debt for like a year and a half. So that’s what I want: Just a level of sustainability.”

Godspeed, Johnny Flynn.