Photo: Mark Murrmann

Editors’ Note: This education dispatch is part of a new ongoing series reported from Mission High School, where education writer Kristina Rizga is known to students as “Miss K.” Click here to see all of MoJo’s recent education coverage, or follow The Miss K Files on Twitter or with this RSS Feed.

For Mission High School principal Eric Guthertz, just walking from the school’s parking lot to his office can be a test of conflict mediation skills: last month one such trip took him two hours and involved “an angry student, an upset teacher, and a maintenance person.” He’s short of breath when he sits down to meet with me in the principal’s office on one typically hectic day. “Please keep the door closed!” he yells to his staff. But within five minutes a young woman is already knocking on his door. He takes it all in stride.

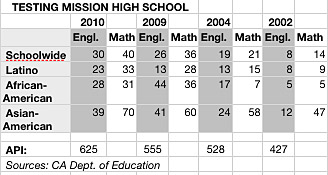

An educator for 22 years, Guthertz has been at Mission High for the past 10—first as an English teacher, then vice principal, and more recently as the school’s principal. Test scores in Math and English among African-American and Latino students have shot up significantly since he took over as head of school three years ago, though he attributes these improvements largely to the work of Stanford’s Linda Darling-Hammond and the “anti-racist” foundation laid by Mission High’s previous principal, Kevin Truitt. This year Mission High showed the largest gains in test scores among all San Francisco high schools, passing 600 points for the first time (out of a total 1,000). Student college acceptance rates are growing; student drop out rates declined from 32 percent to 8 in one year. These changes are especially impressive in California, which ranks 47th when it comes to school funding per student.

How did this happen? Guthertz took 30 minutes out of a typically hectic day to explain:

Mother Jones: Which major changes, in your opinion, contributed to significant increases in your students’ test scores?

Eric Guthertz: About seven years ago, we redesigned the entire school into smaller learning communities based on the work of Linda Darling-Hammond out of Stanford. The first notion was “personalization”—that if students are known and cared for, they will be more successful.

The second was collaboration. We redesigned the school around teams, so that a group of teachers would work with each other all year long, and have time in their daily schedule to talk about how to support students and to reflect on their pedagogy.

The third change is that we also have student advisors. So I may be your English teacher, but I also could be your advisor. And as your advisor I’ll see you two days a week, so that kids are really well known.

Finally, I think the center of all that we are doing is our work around anti-racist teaching. Darling-Hammond has a list of goals, and one of them is this idea of multicultural and equity education. “Multicultural” and “equity” are fine terms, but we felt that “anti-racist” was more honest, named the issue directly, and signaled something quite powerful to the community at large.

MJ: So what does “anti-racist” mean in terms of pedagogy?

EG: [It means] how do you teach? Are you using engagement strategies? Are you valuing oral language as well as the written word? In terms of curriculum, is what you are teaching relevant to kids’ lives?

This work can be really controversial sometimes. If you are going to be an anti-racist school, there is a flip side of that, which is, ‘Well, what does it mean to be racist?’

We have amazing teachers here—really dedicated, thoughtful faculty. But certainly, we had our own internal controversies that we had to deal with. We had to learn how to be reflective and have brave, open conversations with each other. We are now at a level where all teachers desegregate their grades by ethnicity and have conversations about what it means when we have failures of one ethnic group over other. And then actually develop action plans around that.

We have amazing teachers here—really dedicated, thoughtful faculty. But certainly, we had our own internal controversies that we had to deal with. We had to learn how to be reflective and have brave, open conversations with each other. We are now at a level where all teachers desegregate their grades by ethnicity and have conversations about what it means when we have failures of one ethnic group over other. And then actually develop action plans around that.

MJ: Could you give an example of something specific a teacher changed in the class as a result of this approach?

EG: Let’s say a teacher is looking at the standards of American history and comes across a section around the Monroe doctrine or the Westward expansion. While they will be covering the standards, they will also make sure that the issue is covered from a Latino perspective. So, they make an effort to find readings and writing that are connected culturally to the students.

In a geometry class, students are learning to map out their communities and look at how freeways are designed and how certain neighborhoods like Bay View or Western Addition—where many students live—have been reconfigured.

In a math class, they will look at percentages of demographics and how certain communities are shifting around the city. The idea is it’s math, but it’s the real world that kids can connect to.

MJ: How difficult was it to implement these changes?

EG: Some things were hard. In terms of anti-racist teaching, just the culture of self-reflection wasn’t there yet, but it’s very strongly here now.

I was in the classroom when we started the collaborative model and I think in general, it was welcomed. But people weren’t used to working together that closely, and with students.

MJ: Have you had to fire any teachers?

EG: We don’t fire teachers. I’ve certainly done a few evaluations where the teacher needed improvement and in some cases, there is a process called, “non-reelection.” It means that if you are tenured, the district chooses not to re-hire you. I think you have to be very careful, and thoughtful, and make sure that all of the supports exist before you do that.

MJ: Some people argue that some teachers are just not born to be teachers. Do you agree with that?

EG: I think that’s ridiculous. And I also think the “Waiting for Superman” thing is kind of ridiculous. Laying the blame on teachers or the unions is ridiculous. It’s a smoke screen.

MJ: If the teachers’ unions aren’t the main obstacle to quality education, then what is?

EG: Number one is really adequately funding education. The state of California ranks at the very bottom, and we’ve got some grants and funds here and there, but we are still not adequately funded. None of the schools are in the district. And I don’t think teachers are paid what they should be paid.

We are too quick to change things without really knowing what we are really changing. We know from study after study that real change takes 3-5 years. I’m in a Principals Fellowship Program at Stanford and it comes up all of the time. And yet, there are changes from the state and the country without enough time to let things grow and cement and become real programs. We are starting to see change only now in Mission High, but it’s taken six years.

MJ: What’s on your mind, as we go into the next year?

EG: I’m worried about the budget cuts. As we speak, I just got an email forwarded to me with Jerry Brown’s speech about the upcoming cuts in California. And to be honest, I’m worried about kids being safe on the winter break. Just last week, one of Mission High’s former students got killed. I really hope everyone has a safe holiday and everyone comes back to school.