Crazywebsite.com

Marc Andreessen recently wrote a widely shared post about how robots will change the economy. The Netscape founder turned mega-venture-capitalist predicts that we’re headed toward a future when robots do our grunt work, launching a “Golden Age” where humans are freed from wage-grubbing to do “nothing but arts and sciences, culture and exploring and learning”:

Housing, energy, health care, food, and transportation?—?they’re all delivered to everyone for free by machines. Zero jobs in those fields remain…It’s a consumer utopia. Everyone enjoys a standard of living that kings and popes could have only dreamed of…Since our basic needs are taken care of, all human time, labor, energy, ambition, and goals reorient to the intangibles: the big questions, the deep needs. Human nature expresses itself fully, for the first time in history. Without physical need constraints, we will be whoever we want to be.

Andreessen is not the first to daydream about this scenario. My colleague Kevin Drum has written about it extensively, and he shares some of Andreessen’s optimism about what this world might look like:

Global warming is a problem of the past because computers have figured out how to generate limitless amounts of green energy and intelligent robots have tirelessly built the infrastructure to deliver it to our homes. No one needs to work anymore. Robots can do everything humans can do, and they do it uncomplainingly, 24 hours a day. Some things remain scarce—beachfront property in Malibu, original Rembrandts—but thanks to super-efficient use of natural resources and massive recycling, scarcity of ordinary consumer goods is a thing of the past. Our days are spent however we please, perhaps in study, perhaps playing video games. It’s up to us.

Basically, it’ll be pretty sweet. But both Andreessen and Drum caution that this consumer utopia is at least several decades away, and getting there will be a bumpy ride until we come up with new ways for people to get the things they want and need. Because unlike the original Luddites, the British artisan weavers who protested the Industrial Revolution by ransacking garment mills, only to find new work running the machines, huge swaths of today’s workforce aren’t wrong to suspect a dead end ahead. “The Digital Revolution is different,” Drum says, “because computers can perform cognitive tasks too, and that means machines will eventually be able to run themselves. When that happens, they won’t just put individuals out of work temporarily. Entire classes of workers will be out of work permanently.” Which means many of us are headed for Hooverville 2.0, a possibility that Andreessen doesn’t disagree with, at least in the short term.

So how best to brace ourselves for that hiccup on the road to utopia? Here’s where Drum and Andreessen part ways. In Andreessen’s vision, we “create and sustain a vigorous social safety net” for the economically stranded. Sounds great, but how do we pay for it? He veers into late-night infomercial territory here: “The loop closes as rapid technological productivity improvement and resulting economic growth make it easy to pay for the safety net.” The machine will pay for itself!

In other words, robots make everything faster, easier, and better, so humans will make more money selling goods and services, and we’ll all end up with more dimes to spare for those still finding their feet in the robot-powered economy. So we shouldn’t listen to the “robot fear-mongering” about machines coming to eat our jobs—the robot revolution is also a personal-tech revolution, and iPhones and tablets are new reins on the global economy:

What never gets discussed in all of this robot fear-mongering is that the current technology revolution has put the means of production within everyone’s grasp. It comes in the form of the smartphone (and tablet and PC) with a mobile broadband connection to the Internet. Practically everyone on the planet will be equipped with that minimum spec by 2020. What that means is that everyone gets access to unlimited information, communication, and education. At the same time, everyone has access to markets, and everyone has the tools to participate in the global market economy.

Yet plenty of people are less worried about job-stealing robots than the people who will own the robots. As technologist Alex Payne points out, using a smartphone doesn’t mean you’ve got your hands on the “means of production.” Using a robot will never be fractionally or profitable as owning a robot, or a robot factory, or the data center that stores the information collected by the robot. “The debate, as ever, is really about power,” argues Payne. And it’s no secret that a narrow segment of white and Asian males currently occupies nearly all the ergonomic chairs at that table.

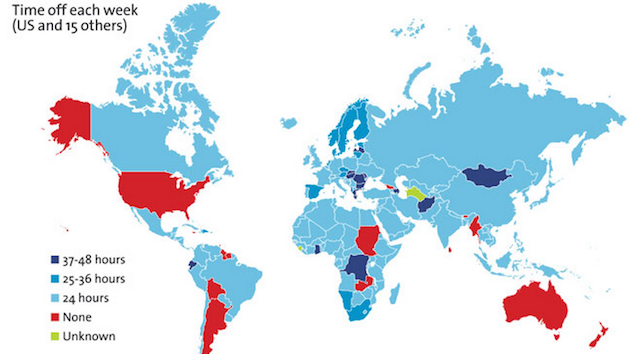

Drum has no doubt that robots are in fact coming to eat our jobs, and it’s the folks with the social and financial capital to buy robots that will call the shots: “As this happens, those without money—most of us—will live on whatever crumbs the owners of capital allow us.” If the robot-owning 1 percent of tomorrow is anything like today’s, then there is little indication that they’re willing to share their spoils. Take a look at this chart of productivity versus worker wages over the last 60 years. Productivity has been shooting up, helped in no small part by greater efficiencies thanks to technology. But worker pay hasn’t been rising alongside these productivity gains:

So where’s all the extra money, the “resulting economic growth” from all this “rapid technological productivity improvement” that Andreessen promises? It’s parked in the pockets of the 1 percenters. Here’s how the share of income is divided between capital owners—the people who own the technology—and labor:

Drum says these metrics are a few of the economic indicators that make up the “horsemen of the robotic apocalypse” in which “capital will become ever more powerful and labor will become ever more worthless.” The other indicators are fewer job openings, stagnating middle-class incomes, and corporations stockpiling cash instead of investing it in new goods and factories. These don’t look so hot, either:

Drum points to a couple of options economists have floated to fend off the robotic apocalypse. The first is redistribution through taxing capital: The wealthy robot owners will employ a few laborers to churn out massive amounts of goods and services, and government turns over a cut of their profits to displaced workers, who spend their days buying the products made by the wealthy’s robots. But corporate execs are likely to fight higher taxes, despite the obvious downsides of an impoverished consumer base. In any case, many of us would probably prefer real jobs to “enforced idleness.” Still, says Drum, “the ancient Romans managed to get used to it—with slave labor playing the role of robots—and we might have to, as well.”

Redistribution could play out in a couple other ways. If people can no longer expect to get by on their brawn or their wits, Drum suggests that government steps in and gives each child a handful of stocks, or maybe a robot of their own—something to give everyone a stake in the sweat-free economy. Other options have been suggested, like Jaron Lanier’s idea of Big Data paying users in “micro-payments” for letting them collect and use our data. But here, too, the linchpin is corporations and their owners’ willingness to share.

The rest of Andreessen’s solutions are straightforward. First, make sure everyone has access to technology and education on how to use it. I’ve argued extensively for the latter, and Drum sees it as a no-brainer. Second, “let markets work” so that “capital and labor can rapidly reallocate to create new fields and jobs.” Yet unless reallocation is the new corporate-speak for fairly redistributing profit, there’s simply no way the rest of us humans won’t get creamed by our robot overlords.

Additional research and production by Katie Rose Quandt and Prashanth Kamalakanthan.