Mother Jones illustration/Julia Zave

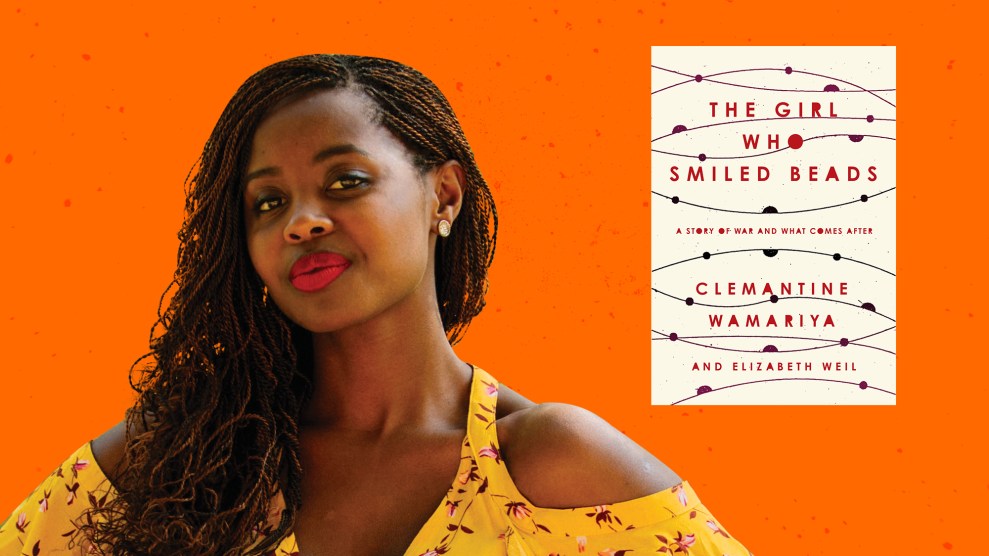

A quick YouTube search for Clemantine Wamariya will bring a clip of her 2006 appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show. Wamariya, then in high school, had won an essay contest about Elie Wiesel’s book Night and was invited onto the show with other winners. She could relate to Wiesel’s experiences in the Nazi death camps, having fled her hometown of Kigali, Rwanda, in the wake of the 1994 genocide. Wamariya and her sister Claire ultimately took refuge in the United States, and although they knew their parents had survived the massacres back home, they hadn’t seen them in more than 12 years.

Winfrey invited the girls onto her show, where she stunned them by bringing their estranged parents and siblings out on stage. The family members enveloped each other in joyful hugs. Wamariya crumbled to the floor in tearful elation. “That’s a moment that will be with me forever,” Winfrey says in the clip. “It’s just beautiful, raw, raw, raw. Pure.” But that moment only offered an introduction to Wamariya’s saga. “Oprah could get someone to listen,” says Wamariya, now 30. “But I needed to continue the story.”

We’re sitting on a small hill in San Francisco’s Lafayette Park on a bright Thursday morning, just blocks from the apartment building where Wamariya now lives. Our perch offers a view of a playground where parents play with their youngsters. We’re joined by Elizabeth Weil, a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and co-writer of Wamariya’s engrossing new memoir The Girl Who Smiled Beads, which comes out this week.

Wamariya, dressed in jeans and a white blouse, had brought delightful soft drinks—passion fruit with seltzer and mint in small mason jars, each kept cool with a large ice cube. This is the same spot where Wamariya and Weil met for countless hours during the writing process. Their book chronicles the sisters’ travails as they make their way across Rwanda, Burundi, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), and South Africa, and Wamariya’s subsequent experiences as a refugee in the US. It’s a visceral and gripping account of what it’s like to try and pull yourself up—to make a decent life for yourself—while wrestling with profound emotional trauma.

“I really wanted to go back to the roots of me—of me choosing me,” Wamariya says. “I felt like I was being pulled so many directions, and I just wanted to bring myself in one place. I wanted to have a narrative that was for me.”

She credits Weil for helping to excavate her memories, which at times felt chaotic and disorganized: “One of the things I think Liz did so well was to be able to pull out places that I didn’t want to go.” The process took almost four years, with Weil helping Wamariya reflect on her experiences with family members and pivotal moments in her life.

The way Wamariya unpacks her story and interrogates how she wants to tell it to others is one of the book’s most captivating aspects. She writes, for instance, that when she started reading Wiesel’s memoir, she “wanted to consume it whole.” Until then, she had been unfamiliar with the word “genocide” and unable to talk about her horrific experiences with family members. “When I read Night I was like, [Gasps], ‘He’s saying that? I can say that?’ I thought that was so shameful,” she recalls. “I found words to be able to communicate what I felt.” Wiesel’s willingness to lay bare his own feelings of darkness and shame gave her courage to do the same.

That’s part of the reason Wamariya is so unwaveringly honest about the details of her life—recounting how her toenails fell off after she had walked hundreds of miles, and how she and most of her fellow refugees were infected with lice in one of the camps. But surviving didn’t exactly make her a saint. Safe in the United States, she distanced herself from her parents, who seemed like strangers to her after so many years apart. And she was often offended when people asked about her time in Rwanda. “I did not want to be a tool or case study,” she writes. “I did not want to be that Rwandan girl.”

Even as she hops from one success to another—attending an elite private school, getting into Yale, being appointed to the board of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum by President Barack Obama, the Oprah invite, this book—she remains overwhelmed by her emotions, and still struggles to connect with her parents. “I think when you survive any intense experience people try to moralize you, a lot of people just try to raise you high, and it’s so not fair to you and to everybody else,” Wamariya says. “I’m hoping that whoever reads [the book] from Rwanda and Burundi, from all the places that I mentioned, I hope that everybody just goes like, ‘Oh goodness! She’s saying that out loud.’ And some people might say, ‘How dare she!’ and there are people who will say, ‘Oh goodness, I can say this,’” she continues. “All I want is whispers in Rwanda. I don’t even need a conversation.”

Wamariya is adamant that she doesn’t believe in letting labels like “refugee” define her. And she hopes that sharing her experiences will help others who have experienced trauma. “I hope that it gives people ownership of their human being, the ownership of their breath, their heartbeat, their body,” she says. “I want people to know that they are the masters, the queens, kings, and gods of their own story.”