Photographer Lynsey Addario says she’s not a war junkie, but you would be forgiven for raising an eyebrow. Since 2001, the Pulitzer Prize winner has raced toward conflict zones in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Sudan. She’s been kidnapped twice and has cheated death more times than she can count. Yet for Addario, whose work and personal journey are chronicled in a striking new photo book, Of Love & War, the daredevil impulse isn’t driven by adrenaline so much as by the stories of people whose lives are upended.

“The ultimate goal,” she says, “is to inspire people to do something.” Addario has stepped away from the front lines to raise her son, but she says she remains dedicated to capturing stories, wherever they may take her. She’s drawn to Yemen, she told Mother Jones, to report on human rights injustices. “It’s a story-driven thing,” she says. “The amount of children who are starving to death, and the human rights injustices that are happening in Yemen…that is the reason why I want to go.”

Mother Jones: You’ve taken millions of photos. How is this your first photo book?

Lynsey Addario: I was planning on doing the book in 2011, but then I was kidnapped in Libya. Soon after, my colleagues and friends Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros were killed there, and I really had a tough time with their deaths. I felt like I needed to process what I had been through rather than spend time looking at my photographs, which were often very violent. When I got pregnant, it felt like the right moment to pull back and focus on life rather than death for the first time in my life.

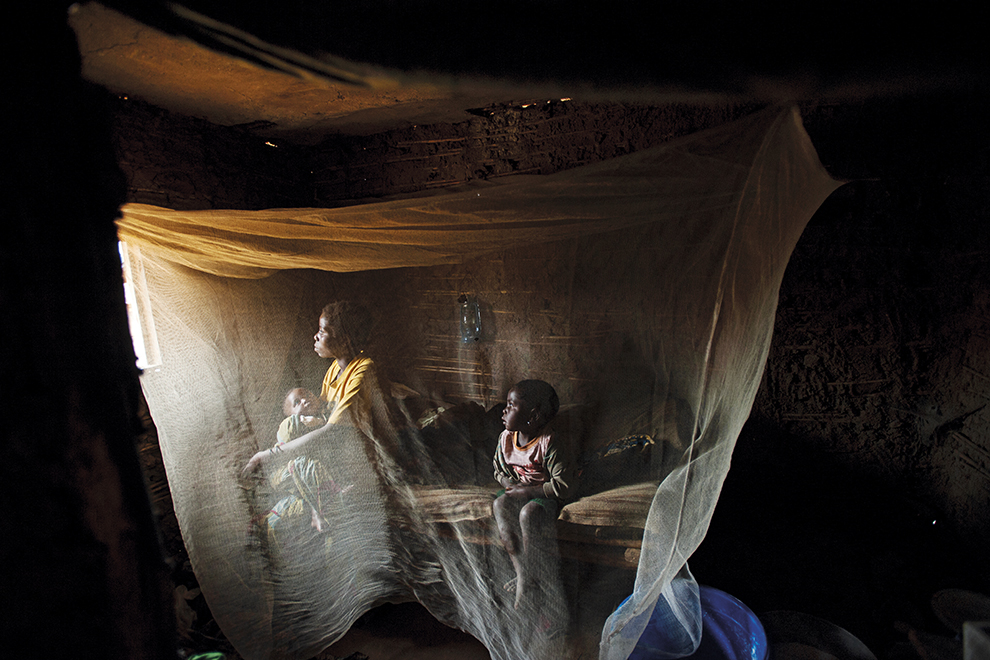

Kahindo, 20, at home with her two children born of rape in North Kivu Province, eastern Congo, April 2008

Lynsey Addario

MJ: What’s one photo you immediately knew you had to include?

LA: There’s a spread from Korengal Valley. The soldiers are carrying the body of one of their men, Sergeant Rougle, during Operation Rock Avalanche. I was able to interview one of those soldiers for the book. People ask, “How did you get that picture?” But for me, it’s much more interesting to talk about what that moment was like for him, carrying the body of one of his best friends.

US troops carry the body of Staff Sergeant Larry Rougle, killed when Taliban insurgents ambushed their squad in the Korengal Valley, Afghanistan, in October 2007

Lynsey Addario

Mamma Sessay, 18, is helped by her sister, Amenata, after delivering the second of her twins at the Magburaka Government Hospital in Sierra Leone in May 2010. Hemorrhaging postpartum, Mamma said repeatedly, “I am going to die.”

Lynsey Addario

MJ: Is that why you include essays and letters along with your photographs?

LA: Photojournalism is a collaboration. It’s not just about taking pretty pictures. I wanted to show my own personal journey, which includes the people I’ve photographed and the writers I’ve worked with. My emotional journey, too. That’s why I included an email I sent to my mother after visiting a children’s cancer ward in Baghdad and an email I sent to an old friend from the time in Iraq when I felt like I was going to die every day. I was terrified, but I continued to go out and shoot.

MJ: What kinds of challenges do women face in this traditionally hypermacho profession?

LA: It still is a boys’ club to some extent. Maybe it’s just the nature of this work. It requires a photographer, male or female, to be away from home for long stretches, and it’s really emotionally and physically taxing. For example, my husband and son have been on vacation for the last two weeks, but I’ve been working. Typically, it’s the man who’s on the road. That’s a stereotype that’s hard to break in my own head, and I’ve been on the road for 23 years. I also think editors are guilty of not assigning and promoting women. One of my editors told me, “I’m not sending you to Mosul because you’re a mother now.” That someone could say that out loud in this day and age is shocking. Do you say that to a man who’s a father? I don’t think so.

Taimaa, 24, with her one-week-old daughter, Heln, in a refugee camp in Thessaloniki, Greece, September 2016

Lynsey Addario

Chuol escaped into a vast swamp when fighters swept into his village in South Sudan in September 2015.

Lynsey Addario

MJ: Have you encountered situations on assignment in which being a woman is beneficial?

LA: I’ve always found it a great advantage. In so many countries I work in, no one takes me seriously. They just think, “Oh, she’s a woman. She’s not going to do any hard-hitting stories.” So they underestimate me. I also get access to both women and men. In the Muslim world, especially, it means I can go into people’s homes and work on very sensitive stories.

MJ: What precautions do you take on assignment?

LA: It’s really important to understand how to dress and how to act. I’m always covered. I don’t wear T-shirts. I don’t wear shorts. I try to be respectful of the cultural norms. Those are things that can ultimately save your life. I always try to travel with a man, whether that’s a fixer or a driver—I don’t go around alone. Someone local who can tell me what people are saying and pick up on signs that I don’t pick up on. They know when a situation could get dangerous.

MJ: In Love & War, you tell the story of Chuol, a South Sudanese boy separated from his family during the civil war. You met him in a refugee camp and managed to track down his mother.

LA: That story and that boy are very special to me. Because I work in such remote areas, it’s rare for me to hear back from the people I photograph. That was one of the few times in my career where I was actually able to follow up on someone I had met. I was able to be the link between the mother and son. I took a video of her and brought it to him in Kenya. I make sure I never compromise my journalistic principles, but I’m also a mother—and I’m a person.

MJ: Speaking of which, how do you balance work and family?

LA: I’m basically always torn. I feel like a horrible mother and not the greatest photographer because I can’t fully give myself to one or the other. People don’t talk about feelings of ambivalence when they get pregnant, because it’s such a taboo. Of course I love my son more than anything, but that’s not the point. I also have this great, incredible love and passion and dedication to my work—and that creates an impossible balance.

Opposition troops burn tires for cover from air strikes at a refinery checkpoint as rebel troops pull back from Ras Lanuf in eastern Libya in March 2011.

Lynsey Addario

A rubber boat with 109 refugees from Gambia, Mali, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Guinea, and Nigeria is intercepted by the Italian navy between Italy and Libya in October 2014.

Lynsey Addario

MJ: Ridley Scott is directing a movie based on your 2015 memoir, It’s What I Do. How do you feel about that?

LA: I’m happy, because young people and people around the world need to see a woman in this role. It’s a great opportunity to show what, exactly, we do. That’s important now that Trump is throwing around the idea of “fake news” and denigrating our profession. We’re the ones risking our lives!

MJ: Will you return to the front lines?

LA: I don’t make hard-and-fast rules. Whether I go to a war zone has always been driven by the story. One of the reasons I spent so many years in Iraq and Afghanistan was because I believed it was important for the American public to see what was happening. I want to go to Yemen because children are starving to death. On the other hand, I always evaluate the risk and what I personally can contribute. War has changed tremendously since I first started. We used to plaster the word “TV” all over our vehicles, and we felt safe. Now we’re a target, no question. There are governments who do not want journalists to show what’s happening, and they will kill them. Marie Colvin was targeted and killed by the Syrian government. But do we still have a place on the front lines? That’s a question I will never say “no” to.

Iman Zenglo, 30, with her five children in a squatters tent outside the Kilis camp in Turkey near the Syria border, October 2013

Lynsey Addario

A Congolese woman displaced by fighting cooks at Kibati camp in Goma, eastern Congo, in November 2008. Civilians living near the front lines were being killed, raped, and abducted by Tutsi rebels and government troops alike, despite a lull in the conflict.

Lynsey Addario