Illustration: Istvan Banyai

Illustration: Istvan Banyai

It is said that a near-death experience forces one to reevaluate priorities and values. The global economy has just escaped a near-death experience. The crisis exposed the flaws in the prevailing economic model, but it also exposed flaws in our society. Much has been written about the foolishness of the risks that the financial sector undertook, the devastation that its institutions have brought to the economy, and the fiscal deficits that have resulted. Too little has been written about the underlying moral deficit that has been exposed—a deficit that is larger, and harder to correct.

One of the lessons of this crisis is that there is a need for collective action, that there is a role for government. But there are others. We allowed markets to blindly shape our economy, but in doing so, they also shaped our society. We should take this opportunity to ask: Are we sure that the way that they have been molding us is what we want?

We have created a society in which materialism overwhelms moral commitment, in which the rapid growth that we have achieved is not sustainable environmentally or socially, in which we do not act together to address our common needs. Market fundamentalism has eroded any sense of community and has led to rampant exploitation of unwary and unprotected individuals. There has been an erosion of trust—and not just in our financial institutions. It is not too late to close these fissures.

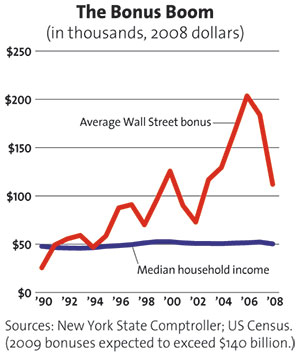

How the market has altered the way we think is best illustrated by attitudes toward pay. There used to be a social contract about the reasonable division of the gains that arise from acting together within the economy. Within corporations, the pay of the leader might be 10 or 20 times that of the average worker. But something happened 30 years ago, as the era of Thatcher/Reagan was ushered in. There ceased to be any sense of fairness; it was simply how much the executive could appropriate for himself. It became perfectly respectable to call it incentive pay, even when there was little relationship between pay and performance. In the finance sector, when performance is high, pay is high; but when performance is low, pay is still high. The bankers knew—or should have known—that while high leverage might generate high returns in good years, it also exposed the banks to large downside risks. But they also knew that under their contracts, this would not affect their bonuses.

What happens when reward is decoupled from risk? One cannot always distinguish between incompetence and deception, but it seems unlikely that a business claiming to have a net worth of more than $100 billion could suddenly find itself in negative territory. More likely than not, it was engaged in deceptive accounting practices. Similarly, it is hard to believe that the mortgage originators and the investment bankers didn’t know that the products they were creating, purchasing, and repackaging were toxic.

Bernie Madoff crossed the line between exaggeration and fraudulent behavior. But what about Angelo Mozilo, the former head of Countrywide Financial, the nation’s largest originator of subprime mortgages? He has been charged by the SEC with securities fraud and insider trading: He privately described the mortgages he was originating as toxic, even saying that Countrywide was “flying blind,” all while touting the strengths of his mortgage company, its prime quality mortgages using high underwriting standards. He eventually sold his Countrywide stock for nearly $140 million in profits. If he had kept the dirty secrets to himself, he might have been spared the charges; self-deception is no crime, nor is persuading others to share in that self-deception. The lesson for future financiers is simple: Don’t share your innermost doubts.

The investment bankers would like us to believe that they were deceived by the people who sold them the mortgages. But if there was deception, they were part of it: They encouraged the mortgage originators to go into the risky subprime market, because it generated the high returns they sought. It is possible that a few bankers didn’t know what they were doing, but they are guilty then of a different crime, that of misrepresentation, claiming that they knew about risk when clearly they did not.

Exaggerating the virtues of one’s wares or claiming greater competency than the evidence warrants is something that one might have expected from many businesses. Far harder to forgive is the moral depravity—the financial sector’s exploitation of poor and middle-class Americans. Our financial system discovered that there was money at the bottom of the pyramid and did everything possible to move it toward the top. We are still debating why the regulators didn’t stop this. But shouldn’t the question also have been: Didn’t those engaging in these practices have any moral compunction?

Sometimes, the financial companies (and other corporations) say that it is not up to them to make the decisions about what is right and wrong. It is up to government. So long as the government hasn’t banned the activity, a bank has every obligation to its shareholders to provide financial support for any activity from which it can obtain a good return. The predecessors to JPMorgan Chase helped finance slave purchases. Citibank had no qualms about staying in apartheid South Africa.

But consider, too, that the business community spends large amounts of money trying to create legislation that allows it to engage in nefarious practices. The financial sector worked hard to stop predatory lending laws, to gut state consumer protection laws, and to ensure that the federal government’s ever laxer standards overrode state regulators. Their ideal scenario, it seems, is to have the kind of regulation that doesn’t prevent them from doing anything, but allows them to say, in case of any problems, that they assumed everything was okay—because it was done within the law.

Securitization epitomized the process of how markets can weaken personal relationships and community. With securitization, trust has no role; the lender and the borrower have no personal relationship. Everything is anonymous, and with those whose lives are being destroyed represented as merely data, the only issues in restructuring are what is legal—what is the mortgage servicer allowed to do (see “Why Banks Love Foreclosure”)—and what will maximize the expected return to the owners of the securities. Enmeshed in legal tangles, both lenders and borrowers suffer. Only the lawyers win.

This crisis has exposed fissures between Wall Street and Main Street, between America’s rich and the rest of our society. Over the last two decades, incomes of most Americans have stagnated. We papered over the consequences by telling those at the bottom—and those in the middle—to continue to consume as if there had been an increase; they were encouraged to live beyond their means, by borrowing; and the bubble made it possible.

The country as a whole has been living beyond its means. There will have to be some adjustment. And someone will have to pick up the tab for the bank bailouts. With real median household income already down some 4 percent between 2000 and 2008, the brunt of the adjustment must come from those at the top who have garnered for themselves so much over the past three decades, and from the financial sector, which has imposed such high costs on the rest of society.

But the politics of this will not be easy. The financial sector is reluctant to own up to its failings. Part of moral behavior and individual responsibility is to accept blame when it is due. Yet bankers have repeatedly worked hard to shift blame to others, including to those they victimized. In today’s financial markets, almost everyone claims innocence. They were all just doing their jobs. There was individualism, but no individual responsibility.

Some have argued that we had a problem in our financial plumbing. Our pipes got clogged, and we needed federal intervention to get the markets moving again. So we called in the same plumbers who installed the plumbing—having created the mess, presumably only they knew how to straighten it out. Never mind if they overcharged us for the installation, then overcharged us for the repair. We should quietly pay the bills, and pray that they did a better job this time than last.

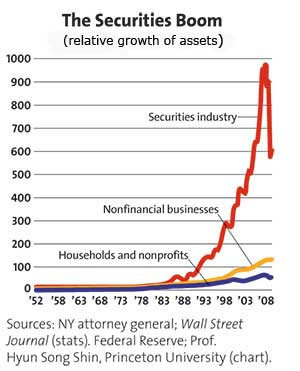

But it is more than a matter of unclogging a drain. The failures in our financial system are emblematic of broader failures in our economic system and our society. That there will be changes as a result of the crisis is certain. The question is, will they be in the right direction? Over the past decade, we have altered not only our institutions—encouraging ever more bigness in finance—but the very rules of capitalism. We have announced that for favored institutions there is to be little or no market discipline. We have created an ersatz capitalism, socializing losses as we privatize gains, a system with unclear rules, but with a predictable outcome: future crises, undue risk-taking at the public expense, and greater inefficiency.

It has become a cliché to observe that the Chinese characters for crisis reflect “danger” and “opportunity.” We have seen the danger. Will we seize the opportunity?

Joseph Stiglitz’ new book is Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy. You can find it online at Powell’s.