UPDATE: Attorney General Eric Holder announced Tuesday that federal authorities have opened criminal and civil investigations into BP. Also today, Kate Sheppard notes that BP has hired Dick Cheney’s former press flack, Anne Womack Kolton, to serve as their new “head of US media relations.”

“What’s been made clear from this disaster is that for years the oil and gas industry has leveraged such power that they have effectively been allowed to regulate themselves,” President Obama said last week in his press conference on the BP oil spill. “I was wrong,” he declared, “in my belief that the oil companies had their act together when it came to worst-case scenarios.”

Ya think? If this isn’t a textbook example of closing the barn door after the horse is out, I don’t know what is. In fact, it isn’t even closing the door so much as acknowledging that the barn actually has a door, which we might want to consider using once in a while if we don’t want the horses running wild. What the president’s statement reminds me of most is Alan Greenspan’s admission, after the economic meltdown took place, that there just might be a tiny “flaw” in his approach to financial regulation. “I made a mistake,” Greenspan told Congress in October 2008, “in presuming that the self-interests of organizations, specifically banks and others, were such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in the firms.”

In the aftermath of his press conference, political pundits seem to be focused on whether Obama—and by implication the federal government—was taking too much responsibility for the spill, or not enough. Only a few have pointed out the patent absurdity of believing in the first place that the oil companies could be trusted to “have their act together” when it came to either preventing or dealing with massive spills. The history of global oil spills over the last half-century shows a pattern of carelessness and ineptitude on the part of the industry—and of failure on the part of governments who tried to intervene after the fact.

When the tanker Torrey Canyon drove straight into the rocks off Land’s End in Britain in 1967, spilling its 31-million-gallon cargo, chemical dispersants were spread on the expanding slick with no result. According to the “Report to the Committee of Scientists on the Scientific and Technological Aspects of the Torrey Canyon Disaster,” the British Air Force was called in to set the oil afire by bombing it. Some of it eventually caught fire; most of it did not. A Dutch salvage team thought they could fix things by pulling the ship off the rocks, but the tow cable broke. The spill ended up killing marine life and spreading glop all over the beaches of Southern England and some in France as well.

In 1969, a well on the outercontinental shelf six miles off Santa Barbara, California, went out of control. All initial efforts to control the spilling oil were as futile. When the flow was finally stopped after 11 days, 3 million gallons had escaped and coated the pristine beaches of Santa Barbara channel. (At the time it was considered a devastating disaster, and helped fuel the fledgling environmental movement in California–though the numbers sound almost quaint compared with the current BP spill.) After the Santa Barbara spill, the U.S. government came up with a plan to keep teams of experts from different parts of government on standby, so they could fly in and assess damage in the event of a spill.

In 1969 alone, the Coast Guard was reporting 1,007 oil spills in US coastal waters. Many others were not reported. (It was standard practice for ships to pump waste oil into the water on approaching port.) That same year, a Woods Hole Oceangraphic research project in the Sargasso Sea, reported “quantities of oil-tar lumps up to 3 inches in diameter were caught in the nets…It was estimated that there was three times as much tar-like material as Sargasso weed. Similar occurrences have been reported worldwide by observers from this as well as other institutions.’’

In 1970 an Onassis tanker called the Arrow hit Cerberus Rock off Nova Scotia. It was the Torrey Canyon all over again. Detergents were sprayed with no effect. The U.S. Army dispatched teams armed with flame throwers to burn it up, which didn’t work. Chemists from Pittsburgh Corning Glass arrived with bags of little glass balls intended to act as wicks for burning the oil, but these did not ignite. Fiberglass collars set up to keep the spreading oil out of a fish processing plant also failed. Attempts to pull the ship off the rocks were futile. Eventually a gale broke the tanker’s back and the stern sank in one hundred feet of water with one million gallons of congealed crude oil aboard. In this case, by pure luck, the remaining oil stayed inside the tanker until a salvage team pumped it out a few months later.

In 1979, Pemex’s Ixtac oil well, in the Gulf off of Campeche, Mexico, suffered a blowout. Through various measures–some of them similar to those currently being used on the Deepwater Horizon spill—the flow of oil from the blown well was slowed from 30,000 to 10,000 barrels a day, but it took nearly ten months for it to be stopped completely. By that time, an estimated 3 million barrels had reached the US Gulf coast.

The 1970s through the 1990s saw more than a dozen spills larger than the Exxon Valdez, pouring oil into the waters off Trinidad, Uzbekistan, Iran, Angola, South Africa, France, Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Mozambique, Chile, and Sweden.

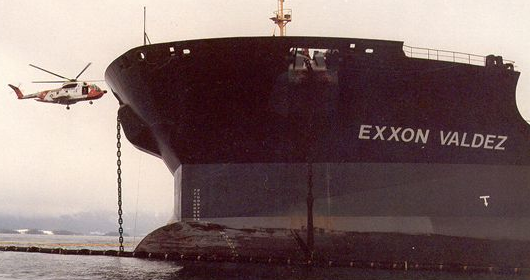

As for the Valdez disaster itself, its effects still linger nearly two decades after the 1989 spill. During that time, suits against Exxon made their way through courts, resulting in a $5.5 billion jury trial settlement. But the Supreme Court later thought this was too much money, and cut the settlement to $1 billion. No fine ever levied against the oil industry has seriously inhibited its ability to keep doing business as usual—or employing lobbyists, or making campaign contributions. And to my knowledge, no oil company executives have ever gone to jail for the environmental devastation caused by their negligence or greed.

This, perhaps, is the real lesson of history when it comes to oil spills: It isn’t enough, even, to close the barn door, if you allow the horses to keep making hay.

If you appreciate our BP coverage, please consider making a tax-deductible donation.