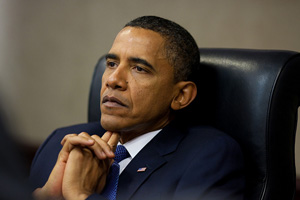

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/whitehouse/4999505200/#/">The White House</a>/Flickr

![]() This story first appeared on the TomDispatch website.

This story first appeared on the TomDispatch website.

“Make poverty history!” A catchy slogan, and an admirable aim, it was adopted by world leaders at the United Nations summit in New York on the eve of the New Millennium. A decade later, it is America which has made history—even if in the opposite direction. The latest US Census Bureau statistics show that, in 2009, one in seven Americans was living below the poverty line, the highest figure in half a century. Last month’s 95,000-plus home foreclosures broke all records.

These were only two of the recent glaring signs of the sagging might of the globe’s “sole superpower,” now heavily indebted to Beijing. Other recent indicators include its failure to corral China into revaluing its currency, the yuan, against the dollar, and to compel Russia, China, India, or even Pakistan to follow its lead in suppressing the oil and natural gas trade with Iran. With Washington failing to impose its monetary or energy policies on the rest of the world, we have entered a new era in history.

America’s Struggling Economy

It’s crystal clear that jobs and the economy have emerged as the key preoccupations of American voters as they approach the November 2nd midterm Congressional elections.

The economic “recovery” is proving anemic. An already weak gross domestic product (GDP) growth figure, 2.4% for the second quarter of 2010, was recently revised downward to 1.6%, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, consisting of the globe’s 30 richest countries, has predicted a paltry 1.2% US expansion in the fourth quarter of the year.

Soon after retiring as vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve, where he served for 40 years, Donald Kohn summed up the dire situation in this way: “The US economy is in a slow slog out of a very deep hole.”

Consider one measure of the depth of that hole: between December 2007—the official start of the Great Recession—and December 2009, the American economy made eight million workers redundant. Even if the job market were to improve to the level of the boom years of the 1990s, it would still take until March 2014 simply to halve the present 9.6% unemployment rate and return it to a pre-recession 4.7%. Little wonder that James Bullard, president of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, warned of the American economy creeping closer to the black-hole years of deflation experienced by Japan in the 1990s.

By now, the Obama administration’s $862 billion stimulus plan has largely worked its way through the system without having had much impact on job creation. And keep in mind that the high official unemployment rate is significantly less than the real figure. It doesn’t take into account part-time workers who would prefer full-time jobs, or those who have stopped seeking employment after countless failed attempts. In the end, the administration’s policy makers seem to have failed to grasp that a recession caused by a banking crisis is always much worse than a non-banking one.

China Roars Ahead

Just as the Obama administration revised those anemic GDP growth rates downward, China’s economy was passing Japan’s to become the second largest on the planet. While the Chinese GDP is steaming ahead at an annual expansion rate of 10%, Japan’s is crawling at 0.4%.

China’s leaders responded to the 2008-2009 recession in the West that led to a fall in their country’s exports by quickly changing their priorities. They moved decisively to boost domestic demand and infrastructure investment by sinking money into improving public services.

While Western governments tried to overcome the investment slump at the core of the Great Recession indirectly through deficit spending, China raised its public expenditures through its state-controlled banks. They provided easy credit for the purchase of consumer durables like cars and new homes. In addition, the government invested funds in improving public services like health care, which had deteriorated in the wake of the economic liberalization of the previous three decades.

Altogether, these measures boosted the GDP growth rate to 9% in 2009, just when the American economy was shrinking by 2.6%. Such a performance impressed the leaders of many developing countries, who concluded that China’s state-directed model of economic expansion was far more suitable for their citizens than the West’s private-enterprise-driven one.

Altogether, these measures boosted the GDP growth rate to 9% in 2009, just when the American economy was shrinking by 2.6%. Such a performance impressed the leaders of many developing countries, who concluded that China’s state-directed model of economic expansion was far more suitable for their citizens than the West’s private-enterprise-driven one.

On the ideological plane, the spectacular failure of the Western banking system on which the private sector rests revived socialist ardor, long on the wane, among China’s policymakers. In response, they decided to bolster state-controlled companies, proving wrong Western analysts who bet that public-sector undertakings would lose out to their private-sector counterparts.

The upsurge in government spending and generous bank lending policies led to increased investments by state-owned companies. Whether engaged in extracting coal and oil, producing steel, or ferrying passengers and cargo, such companies found themselves amply funded to upgrade their industrial and service bases, a process that created more jobs. In addition, they began to enter new fields like real estate.

Overall, the Great Recession in the West, triggered primarily by Wall Street’s excesses, provided an opportunity for Beijing to stress that, in socialist China, private capital had only a secondary role to play. “The socialist system’s advantages enable us to make decisions efficiently, organize effectively, and concentrate resources to accomplish large undertakings,” said Prime Minster Wen Jiabao in his address to the annual session of the National People’s Congress in March.

The Sacred Yuan and Gunboat Diplomacy

In March and early April, there was much sound and fury at the White House about China’s currency, the yuan, being undervalued, and so giving Chinese exporters an unfair advantage over their American rivals. This assessment was faithfully echoed by a compliant media. Pundits anticipated a US Treasury report due in mid-April condemning China’s manipulation of its currency, a preamble to raising tariffs on Chinese imports. Nothing of the sort happened.

Instead, the Treasury delayed its report for three months. When released, it said that, while the yuan remained undervalued, China had made a “significant” move in June by ending its policy of pegging its currency tightly to the dollar. Hard facts belie that statement, highlighting the former sole superpower’s impotency in its dealings with fast-rising Beijing. Between early April and mid-September, the yuan appreciated by a “significant” 1%.

More worrying to White House policymakers is the way Beijing is translating its economic muscle into military and diplomatic power. The controversy surrounding the sinking of the South Korean patrol ship Cheonan in March is a case in point. Following a report in May by a team of American, British, and Swedish experts that a North Korean torpedo had destroyed the vessel, the US and South Korea announced joint naval exercises in the Yellow Sea off the west coast of the Korean Peninsula. China protested. It argued that, since the planned military drill was very close to its territorial waters, it threatened its security. Later that month at a South Korea-Japan-China summit, Chinese Premier Wen refrained from naming North Korea as the culprit and instead emphasized the need to reduce tensions on the Korean peninsula.

Washington ignored Beijing’s advice. It went ahead with its joint naval maneuvers in early July. Six weeks later, it announced another such drill in the Yellow Sea for early September. Incensed, Beijing responded by conducting its own three-day-long naval exercises in the same maritime space. Breaking with normal protocol, it gave them wide publicity. Unexpectedly, nature intervened. A tropical storm approaching the Yellow Sea compelled the Pentagon to postpone its joint maneuvers.

By then, Beijing had locked horns with Washington, challenging the latter’s claim that the Yellow Sea is an international waterway, open to all shipping, including warships. This is an unmistakable sign that the Chinese Navy is preparing to extend its reach beyond its coastal waters. Indeed, plans are clearly now afoot to extend operations into the parts of the Pacific previously dominated by the US Navy.

China’s naval high command now openly talks of dispatching warships to the waters between the Malacca Strait and the Persian Gulf, principally to safeguard the sea lanes used to carry oil to the People’s Republic of China.

Washington’s Iran Policy Challenged

As China’s third biggest supplier of petroleum (after Saudi Arabia and Angola), Iran figures prominently on Beijing’s radar screen. So far, Chinese energy corporations, all state-owned, have invested $40 billion in the Islamic Republic’s hydrocarbon sector. They are also poised to participate in the building of seven oil refineries in Iran. When, earlier this year, European Union (EU) companies stopped supplying gasoline to Iran, which imports 40% of its needs, Chinese oil corporations stepped in. That was how in 2009, with a $21.2 billion dollar two-way commerce, China surpassed the EU as Iran’s number one trading partner. It is estimated that China-Iran trade will rise by 50% in 2010.

Like Russia, China backed a fourth set of United Nations economic sanctions on Iran in June only after Washington agreed that the Security Council resolution would not include provisions that might hurt the Iranian people. Therefore, the resulting resolution did not outlaw either investment or participation in the Iranian oil and gas industry.

Much to Moscow’s chagrin, on July 1st, President Obama signed the Comprehensive Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA) into law. It banned the export of petroleum products to Iran and severely restricted investment in its hydrocarbon industry. It also contained a provision that authorized the White House to penalize any entity in the world violating the act by restricting its commercial dealings with US banks or the government.

Two weeks later, Russian oil minister Sergey Shmatko struck back. He announced that his country would be “developing and widening” already existing cooperation with the Islamic Republic’s oil sector. “We are neighbors,” he emphasized. Russian oil companies were, he added, free to sell gasoline to Iran and ship it across the Caspian Sea, which the two countries share. The Kremlin also warned that if Washington chose to penalize Russian companies for their actions in Iran, it would retaliate. The Russian ambassador to the U.N., Vitaly Cherkin, stated categorically that Russia had closed the door to any further tightening of the sanctions against Iran.

As promised publicly and repeatedly, in August the Russians finally commissioned the civilian nuclear power plant near Bushehr, which they had contracted to build in 1994. It meets all the conditions of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Russia will provide it with nuclear rods and remove its spent fuel which could be used to produce weapons.

Little wonder, then, that Russia and China appear on the list of the 22 nations that do “significant business” with Iran, according to the White House. What surprised many American analysts was the appearance of India on that list, which reflected their failure to grasp a salient fact: “energy security trumps all” is increasingly the driving principle behind the foreign policies of a variety of rising nations.

Soon after the enactment of CISADA, India’s Foreign Secretary Nirupama Rao stated that her government was worried “unilateral sanctions recently imposed by individual countries [could] have a direct and adverse impact on Indian companies and, more importantly, on our energy security.” Her statement won widespread praise in the Indian press, resentful of foreign interference in the hallowed sanctum of energy security. Delhi responded to CISADA by reviving the idea of building a 680-mile marine gas pipeline from Iran to India at a cost of $4 billion.

More remarkably, Washington’s policy has even been sabotaged by political entities which are parasitically dependent on its goodwill or largess.

In a black-market trade of monumental proportions, more than 1,000 tanker trucks filled with petroleum products cross from oil-rich Iraqi Kurdistan into Iran every day. On the Kurdish side, the profits from this illicit energy trade go to the governing Kurdish political parties which have been tightly tied to Washington since the end of the First Gulf War in 1991.

An even more blatant example of defiance of Washington in the name of energy was provided by Pakistan which would be unable to stand on its feet without the economic crutches provided by America. In January, Washington pressured Islamabad to abandon a 690-mile Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project that has been on the planning boards for the past few years. Islamabad refused. In March, its representatives signed an agreement with the Iranians. And a month later, Iran announced that it had completed construction of the 630 miles of the pipeline on its soil, and that Iranian gas would start flowing into Pakistan in 2014.

An Irreversible Trend

In whole regions of the world, US power is in flux, but on the whole in retreat. The United States remains a powerful nation with a military to match. It still has undeniable heft on the global stage, but its power slippage is no less real for that—and, by any measure, irreversible. Whatever the twenty-first century may prove to be, it will not be the American century.

Those familiar with stock exchanges know that the share price of a dwindling company does not go over a cliff in a free fall. It declines, attracts new buyers, recovers much of its lost ground, only to fall further the next time around. Such is the case with US “stock” in the world. The peak American moment as the sole superpower is now well past—and there’s no overall recovery in sight, only a marginal chance of success in areas such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, where the United States remains the only major power whose clout counts.

For almost a decade, Washington poured huge amounts of money, blood, military power, and diplomatic capital into self-inflicted wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Meanwhile, the US lost ground in South America and all of Africa, even Egypt. Its long-running wars also highlighted the limitations of the power of conventional weaponry and the military doctrine of applying overwhelming force against the enemy.

As the high command at the Pentagon trains a whole new generation of soldiers and officers in counterinsurgency warfare, which requires the arduous, time-consuming tasks of mastering alien cultures and foreign languages, “the enemy,” well versed in the use of the Internet, will forge new tactics. Given the growing economic strength of China, Brazil, and India, among other rising powers, US influence will continue to wane. The American power outage is, by any measure, irreversible.

Dilip Hiro, a London-based writer and journalist, is the author of 32 books, the latest being After Empire: The Birth of a Multi-Polar World (Nation Books).