Consider it a campaign contribution. | © PhotoXpress/ZUMA Press.

James Bopp, the conservative mastermind behind the Citizens United case, boasts that nearly all the campaign finance regulations passed in recent history have been dismantled. “Campaign finance regulations used to sit on four legs…now the Supreme Court has eliminated three legs and cut the other one in half,” said the Indiana lawyer, speaking at Ralph Reed’s Faith and Freedom Conference last week. Regulation, he concluded, “is on its last legs.”

Bopp, the current general counsel for the anti-abortion group National Right to Life, has played a central role in dismantling many of the campaign finance regulations that have been enacted since the 1970s. In 2007, Bopp successfully defended Wisconsin Right to Life in its Supreme Court case against the Federal Election Commission, winning a decision that laid much of the groundwork for Citizens United. And while Bopp didn’t argue Citizens United when it reached the high court two years later, he didn’t really have to: The case was his brainchild.

Bopp proudly points out that the Supreme Court has now repeatedly been swayed by his argument that corporate speech is covered under the First Amendment and that corporations should therefore be allowed to spend as they please. At the Reed event, however, he added that corporations should have the right to remain anonymous if they decide to spend money in an election—and that the Founding Fathers would have wanted it that way. He points out that the famous authors of the Federalist Papers used pseudonyms to sign them. “If you don’t know the author of the argument, then all you can do is talk about the argument, the merits of the argument,” he told me.

Good government groups—along with many Democrats—say such anonymous spending allows corporations to unfairly cover their tracks, leaving consumers, shareholders, and voters in the dark about where companies are funneling their money. But Bopp, along with his co-panelist, the Heritage Foundation’s Hans von Spakovsky, said that granting corporations such anonymity in the political sphere was precisely the point of Citizens United. If third-party groups were forced to disclose who their donors were, then individual donors as well could be “subject to harassment and loss of employment because they’re against homosexual marriage in places like California,” claimed von Spakovsky, a former FEC official under Bush. The logic is that corporations could also face retaliation if they were actually held accountable for where their money was going—and that they would become vunerable if there were more sunlight.

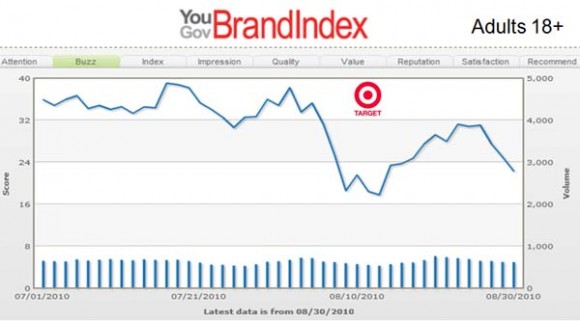

That’s exactly what happened to Target, the retail giant, after it was discovered to have given money to a group running ads in support of Republican gubernatorial nominee Tom Emmer. Progressive activists were furious—but at least they, for once, knew exactly where the money was coming from. Bopp agreed that Citizens United wasn’t likely to open up the floodgates for massive spending by individual corporations, pointing to Target’s PR disaster: “It is a good example of why I think for-profit corporations are not going to do this,” Bopp said. “It’s too easy for people to find these things out.” For Bopp, it’s not enough that Citizens United liberates corporate speech. He also thinks they shouldn’t have to tell their shareholders, customers, or the general public where their money goes.

Toward the end of our interview, Bopp suddenly interrupted me with one of his hallmark arguments—that a wide range of groups across the ideological spectrum are classified in the tax code as a “corporation” and should share the same right to free speech. “Mother Jones has a right to write articles. Are you a corporation?” he asked me. “We’re a non-profit corporation,” I replied. “Well,” he said, with a smile. “Then you’re one of those evil corporations…You’ll have to stop this.”