<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Censored_stamp.jpg">Piotr Waglowski</a>/Wikimedia Commons

A spokesman for WikiLeaks this weekend offered details of the website’s redaction process and said the group is “open to the possibility” of handing journalists uncensored versions of certain documents in its Iraq War logs.

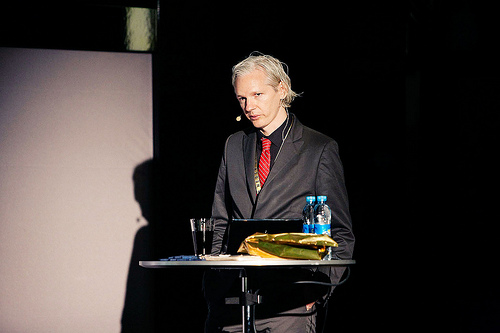

Kristinn Hrafnsson, a representative of the website who appeared at a press conference in London Saturday with site chief Julian Assange, made the statements in a video interview on a WikiLeaks YouTube channel that the group appears to have set up later that night. In the video (embedded below), he explained how the site changed up the editing methods it had employed in an earlier dump of classified military reports from the Afghan War. “I’m sure there are going to be tricky questions, especially in regard to the redactions,” he said.

In the two days since WikiLeaks released its 391,831 Iraq “significant activities” reports to the public, some journalists and readers have murmured about the heavy censorship of key terms—heavier even than the Pentagon’s redactions, in some cases. That was largely in response to charges by both government authorities and human-rights groups that the organization’s uncensored Afghan war logs could put sources in physical danger.

Hrafnsson confirmed that the Iraq redaction process was much more rigorous. “This time around, we took a different approach, which can be described basically as a reverse approach to redaction,” he said:

At the outset, you decide that basically everything in all the reports is harmful until proven otherwise. So little by little, you approach the material and reinstate words, locations, et cetera…There [are] of course limited resources, but the end result, whether it takes weeks or months, should be very limited and just the necessary redactions for harm limitation, so we can possibly call on academic institutions or other media organizations to help out in that progress.”

Interestingly, that “reverse approach” is a more restrictive threshold than even the US government’s classification process, which (theoretically) is to leave all data unclassified unless there’s a clear national security interest in concealing it. (On entering office, President Obama signed an executive order making that standard explicit: “If there is significant doubt about the need to classify information, it shall not be classified,” it states.)

WikiLeaks’ heavy editing means the group might pass uncut Iraq reports to agencies interested in parsing out their deeper significance, Hranfnsson added: “We are also open to the possibility, because of the material being fairly overly redacted as is, to hand out upon request the material to journalists who are interested in special fields, special categories if I may say so, or some special events, or time frames.”

Despite that gesture, Hrafnsoon took the opportunity to chide journalists for getting it wrong in much of their earlier reporting on Iraq. The war logs tell “a story of the failings of the traditional media, of reporting properly on the Iraqi War in the period,” he said. “That should be something that should call for a bit of soul-searching within the media, where they were too much relying on the military for information.”

WikiLeaks’ YouTube channel also showcased interviews with several media collaborators on the Iraq logs, like Josh Dougherty of Iraq Body Count, who’s been trying to match individual military reports to public records of incidents, and Ian Overton of the Bureau for Investigative Reporting, which has produced videos on the Iraq War logs for the UK’s Channel 4 and Al-Jazeera.

But Hrafnsson’s exposition on the war logs’ significance, and his defense of the redactions, were the biggest revelations on the site. He conceded that critics would continue to knock WikiLeaks for its editing job, on one hand, and the possible harm to sources posed by the leak, on the other.

“We just tell the truth about how we approached it…[and] why the material is necessary to be in the public domain,” he said. “That is the only answer we can give to criticism, basically. And the right one.”