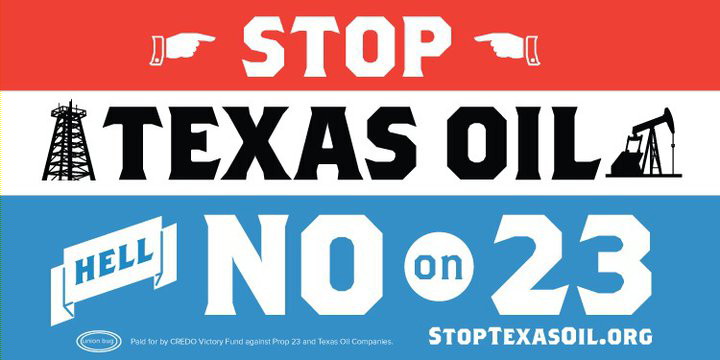

Environmentalists were quite relieved when California voters soundly rejected a ballot measure that would have delayed implementation of the state’s landmark climate law—but perhaps they shouldn’t be. While that ballot measure was shot down, another initiative, Proposition 26, snuck in—and it could very well undermine the climate law that citizens voted to protect.

The measure expands the definition of a “tax,” and would require a two-thirds majority of the California’s legislature to approve any new fee on companies or taxpayers instead of a simple majority. This, of course, would make it considerably harder to levy fees on things like pollution, alcohol, or tobacco. Prop. 26 didn’t get very much attention, but it quietly drew support from a number of companies who oppose new fees. Chevron, Exxon, and PG&E contributed big bucks to the $18 million campaign to pass the measure.

Opponents of Prop. 26 were caught completely off-guard by its success; it passed by a 6-point margin, with 53 percent of voters supporting it. “We actually thought we were going to beat them, so I’m not sure what happened,” Heidi Pickman, a spokesman for the “No on Prop. 26” campaign, told the LA Weekly. “They had a lot of money.”

The measure could have profound implications. A UCLA School of Law study, for example, found that it “could have substantial and wide-ranging impacts on implementation of the state’s health, safety and environmental laws.” The study lists the Global Warming Solutions Act (also known as AB32)—the very law that voters defended against Prop. 23—as one measure that would suffer most due to the two-thirds majority requirement:

The state currently uses regulatory fees—the type that would be transformed into taxes by Proposition 26—to help pay for its environmental and public health programs. Proposition 26 would make it harder to impose or revise fees to fund these programs in the future.

AB32 was passed in 2006, but implementation begins next year and would likely include some increased fees on oil, gas, and other pollution sources that the law aims to cut. It’s not clear to what extent the two-thirds requirement would actually impact AB32, since it was signed into law before the change, but the UCLA study predicts that, “[a]t a minimum, we expect that industry would mount a challenge to future AB 32 fees.”

So while the overwhelming majority—61 percent—of California voters weighed in to support their climate law, this other measure could still cause major problems in implementing it. It looks likely, however, that the issue will end up in court, and opponents are hoping they can prevent it from taking effect.