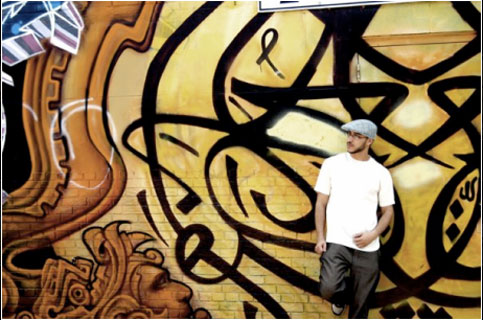

When Khaled M was a little kid, he dreamed of sneaking into Libya, assassinating Muammar Qaddafi, and freeing the country. That’s not so weird considering his father was thrown into a Libyan jail and tortured for five years for taking part in a student protest against the regime. His dad escaped from jail and fled to Tunisia on foot, but Khaled still remembers how the first few years of his life was spent running from country to country dodging the dictator’s minions. “We would be in Morocco or Sudan and set up a radio station and then maybe after a few months Qaddafi’s people would get a whiff of it and chase us, and we’d have to drop everything and leave,” says Khaled, who is now a 26-year-old Libyan-American rapper.

Khaled’s family eventually settled in Lexington, Kentucky—”the most random” place they could think of—in a bid to foil their pursuers. In Lexington, Khaled was raised in a community of political refugees and dissidents, including members of the National Front for the Salvation of Libya. He has never been to Libya himself—his family’s been blacklisted there, and he could risk execution if he dared go—but he still feels a strong connection to the country. “It’s a country that everyone around me has fought to liberate,” Khaled says.

So, when Libyans rose up, Khaled and a network of resistance groups joined forces to create a music video entitled, “Can’t Take Our Freedom,” a rebel anthem that’s garnered attention from ABC Global News, CNN, and Complex magazine. It’s a catchy protest song featuring Iraqi-British rapper LowKey and some exclusive footage from inside Libya. I asked Khaled about growing up in exile, Libya’s music scene, and what getting rid of Qaddafi might do for the country’s artistic culture. Check out the video at the end of the interview.

Mother Jones: What’s Enough Qaddafi? And how did you get the footage you used in the video?

Khaled M: Enough Qaddafi was something that some friends of mine who were also children of Libyan exiles created when Qaddafi came to the US for the first time to speak in front of the UN. It was created to raise awareness about Qaddafi, his history, his crimes. A lot of people are largely ignorant about what’s going on and what’s been going on. People, especially in the West, are familiar with Lockerbie and Qaddafi’s back and forth with Ronald Reagan, but they’re not aware of his brutal, tyrannical oppression with his own people. So we wanted to raise awareness for that. Specifically, to make sure that he wasn’t welcome here in the States. We all met in New York and protested his visit, but it gained wings from there. When everything first started happening in Libya, we met up in Washington, DC, with a group of Libyan exiles and children of Libyan exiles and Libyan Americans from all across the country. We intended initially just to demonstrate outside the White House. But what it turned into, for about a week at least, was 30 Libyans packed inside a house. It was like a CNN newsroom, everybody with laptops and tweeting and facilitating stuff through the media, creating websites and getting audio, video—all sorts of personal accounts from people inside of Libya and trying to filter that through the media and the West because at that time no journalists had been into Libya yet. Part of the images and stuff we gathered is exclusive footage from folks inside Libya. Some of it personal pictures and video that we’ve had over time, and some of it is coverage that’s been shown on other news stations.

MJ: It’s gotten some media attention, but do you think it would have gotten any notice in the absence of a Libyan uprising?

KM: I think it’s timing. I think it’s very relevant. It’s something that Americans are starting to become more interested in and want to learn more about. And with it being a hip-hop song, it reaches an audience and informs an audience that normally wouldn’t hear about it. It reaches a demographic of people that maybe don’t turn on the news every single day and read about what’s going on in Libya.

MJ: What do you know of the music scene in Libya?

KM: I would say some of the most popular music is not created within its borders. Within Libya, they have like a Middle Eastern version of American Idol, for example, and twice Libyan artists have won that competition. Once they win, the government sort of takes hold of them and makes pro-government, pro-Qaddafi music. That’s the type of music that’s allowed to get popular. Everything that’s popular outside of that in Libya is sort of an underground subversive culture through YouTube and Facebook.

MJ: Who else is producing Libyan protest music?

KM: There’s a hip-hop artist named Ibn Thabit, and he raps in the Libyan dialect. It’s not in English. He probably came out a year or so ago and he’s been always making anti-Qaddafi music. He’s always been part of the opposition. And his identity is unknown. He goes by an alias. His images aren’t in any of his videos. He’s also definitely the voice for a generation in Libya, for the majority of the people, and especially the youth who oppose Qaddafi.

MJ: Hip-hop resistance music has been coming out of Tunisia and Egypt also. What attracted you to rap?

KM: I don’t think it was a conscious decision. I had older “uncles” that lived with me who always used to listen to Tupac, so even when I was in the first grade, second grade I used to listen to Tupac. I was always part of a community of political refugees in Lexington, and naturally I feel like oppressed people, or people that are part of resistance movements and that usually don’t have a voice through traditional means, I think those people gravitate towards hip-hop. And hip-hop represents people that are part of the struggle.

MJ: What was it about Tupac you related to?

KM: Well, generally I can relate to it because we grew up extremely poor. McDonald’s was something that was offered on your birthday as a treat. I grew up in a poor community where a lot of people around me, the role models older than me, sold drugs, or were in jail, or got shot and killed. But in Libya—it’s a true oppression, an extreme struggle that’s different than here in America. Here you can live in the hood and still have cable TV and buy new shoes. Over there, it’s a different level of oppression because people aren’t even allowed to speak up for what they believe in.

MJ: Do you think a lot of innovative sounds that could come out of Libya with Qaddafi gone?

KM: I think not just sounds. The country will flourish creatively once Qaddafi’s gone in regards to music, poetry, writing, TV, film, the arts. The people have been wearing a muzzle for more than 40 years now. And for the first time they’re allowed to taste freedom, they’re allowed to taste expression, and speaking their minds. I think it’ll definitely cultivate creative minds.

MJ: Do you ever feel pressure to make political music that addresses the situation in Libya?

KM: I don’t think I consciously seek out political music and I definitely don’t consciously create political music, but naturally my music is always a reflection of myself, and I try to avoid talking about stuff I’ve never been through or anything that’s idle. I want my music to be a mirror image of me. So naturally my political beliefs come out.

MJ: What are some of your favorite political songs?

KM: You know that song Poison, by Nas. It’s on his album Stillmatic. When I first heard that song, I really, really connected to it. It’s about everything from radio, TV, abortion, plastic surgery, white Jesus—he speaks about a lot of things that he considers ills in our society. There’s also a newer song by Lupe Fiasco called “Words I Never Said.” It’s really shocking to hear a mainstream artist speak about the issues that he’s speaking on because he literally talks about 911 how he thinks it’s a set up. He openly calls Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh racists. He speaks about how he didn’t vote for Obama because of his silence when Gaza Strip was getting bombed. It’s a really interesting song.

MJ: Protest music risks being preachy and pedantic. Did you consider those types of pitfalls when writing “Can’t Take Our Freedom”?

KM: Definitely. I’m very aware of avoiding that. In my music or my interviews, when I suggest to people how they should live, how they should run their life, all I’m doing is offering a piece of myself and where I’ve been and what I’ve learned, and people can take away from that what they wish.

MJ: What was it like growing up as you did?

KM: I grew up in a community of political refugees who had very, very close ties with each other. Not because they happened to be Libyan but because they struggled with each other. They fought for the same cause. Most of the people that were in Lexington knew each other before they had moved to Lexington. They had witnessed each other’s family members die or get killed. And they had made a sacrifice. They had left everything behind—money, career, family. My father escaped from Libya, and he never ever saw his mother again. He never saw his brothers again, his sister again. And that’s not a unique story; that’s a very common tale told by the Libyan exiles here in America. Other than my brothers and my mom I didn’t have family around me. And this was the same for the other Libyans in Lexington. We didn’t grow up in a community where we had our grandparents there, and our uncles and aunts and cousins. We were each other’s family. And that’s a beautiful thing.

I’m still a Kentucky boy at the end of the day. I still grew up with that Southern charm. I’m a big UK Wildcats fan. And I love Southern food. In those ways, I’m still a normal Lexingtonian. But there’s other things that were very unique. Like whenever I met a new Libyan, I didn’t know if they were really with us or if they were a spy sent by Qaddafi’s goons. My legal name is different than my actual real name. I didn’t find out what my true real name was until after I became an adult. I’m used to having different names and my father having different names and not knowing who you could or couldn’t talk to. Different things that seemed normal or routine to me are actually very bizarre looking back on it as an adult.

MJ: What do you think about the US intervention?

KM: The no-fly zone is something across the board Libyans are in favor of. I feel like as long as they stick within the parameters of the UN resolution and we don’t see troops on the ground and we don’t see occupation, then it will be a good thing. If they keep it specifically targeted like it’s been during the last few days and don’t create any civilian casualties—and specifically target Qaddafi’s barracks and his anti-aircraft guns and his capabilities; as long as it stays meticulously done, then it’s a beautiful thing.

MJ: If Qaddafi falls, do you think you’ll go back to Libya?

KM: Definitely. I won’t only visit, I look forward to being part of the rebuilding process. America will always be a home for me. I’m sure I’ll always come back here and be back and forth. But I look forward to going back.

Click here for more Music Monday features from Mother Jones.