For Occupy Wall Street to keep gaining steam, it must begin to attract people who aren’t part of the typical protest crowd. Based on my experience at Zuccotti Park this weekend, this has begun to happen—in spades. Throughout the day I ran into people who’d never been to a protest until now. None of them belonged to activist groups or trade unions. They’d simply heard about the occupation and decided to come. Some were blue-collar folks out of work, others college students who feared they’d never land a job. Here are four of their stories:

Kevin Monahan, a laid-off sanitation worker, says the Occupy Wall Street activists aren’t scared of terrorists. “We are scared of living alone on the streets for the rest of our lives.” Josh Harkinson

Kevin Monahan, a laid-off sanitation worker, says the Occupy Wall Street activists aren’t scared of terrorists. “We are scared of living alone on the streets for the rest of our lives.” Josh Harkinson

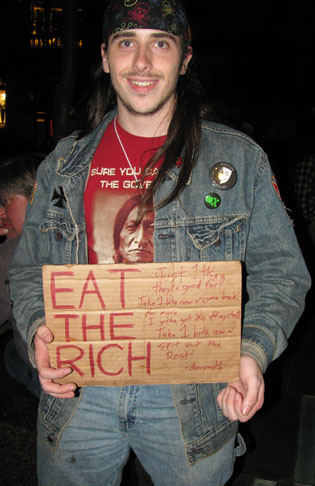

Kevin Monahan, laid-off sanitation worker

Monahan is hard to miss at McDonald’s, where a long line of occupiers waits for the restroom. He wears long hair wrapped in a skull-pattern headband, a jean jacket with a Confederate Flag patch, and a button on his lapel that says, “The rich bailed out, the poor sold out.”

About a year ago, Monahan lost his job as a garbage truck driver in upstate New York. At 24, he’s embarrassed that he’s had to move back in with his parents. He tried attending college for a while but dropped out when he lost his financial aid. He now competes with teenagers for minimum-wage cashier jobs. He knew that Wall Street was partly to blame for his problems, but when he saw a YouTube clip of New York cops macing peaceful demonstrators at Zuccotti, “it just threw fuel on the fire.” He begged friends for gas money and drove down to Manhattan.

Monahan doesn’t exactly know how to describe his politics. “I don’t trust the government whatsoever,” he says. He’s a fan of Ron Paul and a believer in his campaign to “End the Fed.” But he also strongly believes that the wealthy need to pay more taxes. He hates Glenn Beck and Bill O’Reilly and scoffs at the concept of trickle-down economics, which he sees as a tax on the poor for the benefit of fat cats. “Take as much as you can, that’s the whole point of capitalism,” he says. “Get as rich as possible, profit is the only means. So what do we do when they have it all?”

As he talks, his voice often wavers with emotion, and his eyes go glassy. At home he often feels alone; here people constantly embrace him. “I’ve run into socialists, communists, liberals, gutter punks, rastas, thugs, and believe it or not, everybody is getting along,” he says. “We have the same common enemy. None of us is scared of terrorists. We are scared of living alone on the streets for the rest of our lives.”

Duncan Blount, college student

“Russell Simmons came down and sat with us!”

“Russell Simmons?!” Blount has to say it back to his friend to believe it.

It’s not the sort of thing that happens every day, especially not to students from a small college town in Kentucky. Of course, when you’re part of a pack of 41 people who’re all wearing a the same t-shirt, you get attention.

The “Blue Crew” shirts were originally designed for Berea College’s pep team but never used, so Blount and his fellow students reappropriated them for their Occupy Wall Street squad. Not that the school is sponsoring them. A day before the group was set to depart, school administrators said they students shouldn’t go and pulled $8,000 in funding for the trip, citing the dangerous clashes with law enforcement.

Duncan Blount, a college student, wants Occupy Wall Street protesters to focus on getting corporate money out of politics. Josh Harkinson

Duncan Blount, a college student, wants Occupy Wall Street protesters to focus on getting corporate money out of politics. Josh Harkinson

Tiny Christian Berea College has a history of deep involvement in social movements. A ’60s era president of the school famously loaned students his car so they could drive to the civil rights protests in Birmingham. But Blount says safety concerns weren’t the only reason the school backed out on funding the trip. “I was told by the school’s vice president that we should think about what we are doing because the majority of our tuition is paid for by Wall Street,” he told me. It turns out that Wall Street investors are major contributors to the school’s endowment.

Rather than give up, the Blue Crew set out to fund the trip on their own—no small task given that a requirement of admission to Berea is that one must come from an economically disadvantaged family. “Everyone in the room stood up and started pulling money from their pockets,” Blount said. “We were not going to let this hold us back from something that we believe in.”

The group traveled on a shoestring, staying with friends and anyone else who will take them. Blount planned to spend last night in a Baptist church in Newark, New Jersey. It would have been tough to pull off for anyone, let alone a 20-year-old sophomore who’s never been to a protest.

If Blount could convince the occupiers to focus on one issue, it would be getting corporate money out of politics. Yet he’s mostly here to take it all in. “I’m just learning about all of this,” he says. “It’s blowing my mind and pissing me off, but I’m doing something about it.”

Michael Smith, a machine operator, sees Occupy Wall Street as a way to take control of his future. Josh Harkinson

Michael Smith, a machine operator, sees Occupy Wall Street as a way to take control of his future. Josh Harkinson

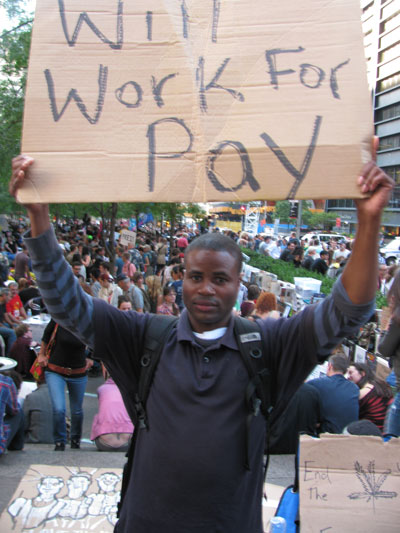

Michael Smith, machine operator

When I find Smith holding his sign on a sidewalk full of testy police officers, his eyes light up and words spill out in torrents. He’d heard about the occupation on television in September and has come down from his apartment in the Bronx every weekend. “People are losing their jobs and losing their houses and nothing is being done about it,” he says. “I’m not against capitalism; I just think that it should be more fair.”

Smith, 36, works as a production machine operator for a New York publisher—a blue-collar job in one of New York’s most struggling industries. About a year ago, his employer cut his hours in half, and he hasn’t been able to find anything else to fill the gap. He knows that many others are also suffering from the downturn, but none of them are rich. “They say that everything has gotta be spread across the board, but the poor and middle class are bearing everything,” he says. “The rich have got to be taxed.”

Never someone who considered attending protests, Smith sees now Occupy Wall Street as a way to take control of his future. “I wanted to get involved because I believe that people can’t keep sitting on the sidelines.”

John Wells, 31-year-old call center worker, says voting for change isn’t enough. “We’ve got to shout change!” he says. Josh HarkinsonJohn Wells, call center worker

John Wells, 31-year-old call center worker, says voting for change isn’t enough. “We’ve got to shout change!” he says. Josh HarkinsonJohn Wells, call center worker

“We tried to vote change and that wasn’t good enough,” Wells tells me, holding his sign high above the edge of a thundering drum circle. “We’ve got to shout change!”

That’s no small thing coming from a 31-year-old North Bergen, New Jersey, call center worker who admits he’s “always been a down the line kind of guy.” But his mom was recently laid off, and he’s met plenty of others in the same boat. “I believe we’ve got to do something about it.”

Wells seems like he could get used to this activism thing. “I feel totally empowered right now,” he says. “I feel great being out here.”