Illustration: Brian Stauffer

[Editor’s note: This story first ran online in December, 2011. This is the updated version that appears in the March/April 2012 issue of the magazine.]

“THIS IS A COLLECT CALL from a correctional institution,” says the robotic female voice at the other end of the line. After a moment of confusion, I realize it must be Felix Garcia, whom I’d visited several weeks earlier in a northern Florida prison. He’s serving a life sentence on a robbery-murder charge for which his own brother now admits to framing him.

Felix is deaf, which is why he’s using a TTY operator. I’d sent him a card for his 50th birthday, a picture of flowers and some lame words of encouragement. Now he’s calling to thank me and to plead for help. Four of his fellow deaf inmates have tried to commit suicide, he explains; one somehow managed to swallow a razor blade. It sounds like Felix is thinking about doing the same. “Please,” the voice intones, “will you phone my lawyers? I can’t get through to them.”

Felix lost most of his hearing when he was still a kid. For most of his three decades behind bars, starting at age 19, he—like most deaf prisoners in America—has been housed in the general population with few services for his disability. He’s been raped, targeted by other prisoners, and ignored or taunted, he says, by guards who think he’s faking. Last year, he tried to hang himself.

“Felix,” I plead awkwardly. “You are not going to kill yourself.”

“I won’t do it,” he says finally. “I have Jesus.”

I repeat: “Do not kill yourself.”

“Yes, sir.” The call cuts off.

After a few minutes, I pick up the phone and call Pat Bliss, a 69-year-old paralegal who for the past 15 years has served as Felix’s advocate, crafting defense strategies, writing motions and briefs, and helping usher his case through the courts. The lawyer who helps Pat with the case calls her “an angel.” Which is something Felix needs more than anyone I’ve ever met.

Felix grew up in Tampa, one of six children in a working-class Cuban American family. Almost from birth he suffered from severe ear infections. He struggled with headaches and earaches and often missed school. He would stuff cotton balls in his ears, a former schoolmate recalls, to prevent pus from leaking out.

A good-looking kid with a sweet demeanor, he managed to make it through school by getting girls to tutor him—or help him cheat. Still, by high school Felix was having difficulty understanding people even when they spoke up, and he struggled to speak clearly as he lost the ability to hear his own voice. “I hear sounds, and I hear voices,” he would later tell a judge. “But I can’t make out the words unless I am looking at the person.” It felt, he noted, like being underwater.

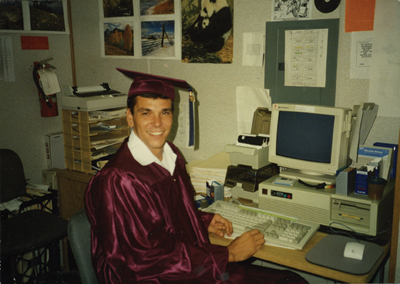

Felix Garcia celebrating his GED in 1984 Courtesy Pat Bliss.

Felix Garcia celebrating his GED in 1984 Courtesy Pat Bliss.

After graduating, Felix had a run-in with the law for passing a bad check. (He got probation.) He worked as a brick mason, and when he was 19, he and his girlfriend, Michelle, had a baby girl they named Candise. Occasionally he would hang around with his siblings, some of whom had gotten involved, as he puts it, with “the street.”

On August 4, 1981, his brother Frank, his sister Tina, and her boyfriend, Ray Stanley, took Felix to a pawnshop. Frank had a ring he wanted to hock. Saying he didn’t have ID on him, he asked Felix to sign the pawn ticket. The ring, it turned out, belonged to a man who’d been murdered the day before at a motel. Six days later police, having traced the ticket, arrested Felix at Tina and Ray’s house.

Felix insisted he knew nothing about the crime. Michelle and her mother later testified that he was with them at the time of the killing. But Frank, who knew the victim and had left his prints at the scene, fingered Felix as the killer and was convicted of armed robbery and second-degree murder—a lesser charge than he might have faced. Tina, who married Ray shortly after the arrest, also agreed to testify against her younger brother.

At trial, in 1983, a doctor declared that Felix had severe hearing loss—he still kept cotton in his ears to stanch the pus. The court issued him a hearing aid and a loudspeaker, neither of which helped him discern speech. Felix tried to read lips, but he was seated far from the witness box, and the prosecutor often faced in the wrong direction. For the most part, he had no idea what was going on.

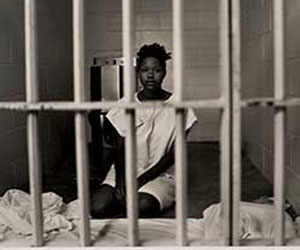

IT’S HARD TO KNOW how many deaf people are locked up, since prison authorities don’t generally bother to keep count. While studying Texas prisons a decade ago, Katrina Miller, a corrections official turned academic researcher, discovered that a whopping 30 percent of the inmates met the clinical threshold for “hard of hearing.” In any case, the experts I spoke with say Felix’s experience is not unusual.

On paper, anyone with a disability is legally protected against discrimination. In practice, institutions of justice are often ill equipped or disinclined to deal with special needs. “Deaf people have a hard time,” says retired McDaniel College psychology professor McCay Vernon, an authority on the deaf who is familiar with Felix’s case. “The courts—judges, prosecutors, defense lawyers—just don’t understand what they’re up against. Turning up the sound system doesn’t mean the defendant better understands what’s going on. He just hears more noise.” Courtroom sign interpreters often can’t keep pace with proceedings, Vernon adds, and many deaf people simply lack the vocabulary to understand. “Their ability to read can lag far behind hearing people.”

Perusing the trial transcript years later, Pat asked Felix why he’d been so quick to answer “yes” to one question after another. “If I say no, they’re going to think I’m stupid,” Felix replied. “Plus I wanted to get off the stand and go home.” By the time the trial began, he’d already been in jail for two years.

In July 1983, Felix was convicted on the basis of his siblings’ testimony and the signed pawn ticket—the only physical evidence against him. He received a life sentence for first-degree murder and a concurrent 99 years for armed robbery and was placed in a maximum-security lockup. He and Michelle parted ways, and he never saw her again. His mother visited a few times, but then his parents wrote Felix a letter saying they were moving to Tennessee and that he shouldn’t look for them if he ever got out. By 1987, when he finally got an operation to take care of the pus drainage, Felix was living in a kind of sensory solitary confinement—until Pat Bliss found him.

Felix in 1999 Courtesy Pat Bliss.

Felix in 1999 Courtesy Pat Bliss.

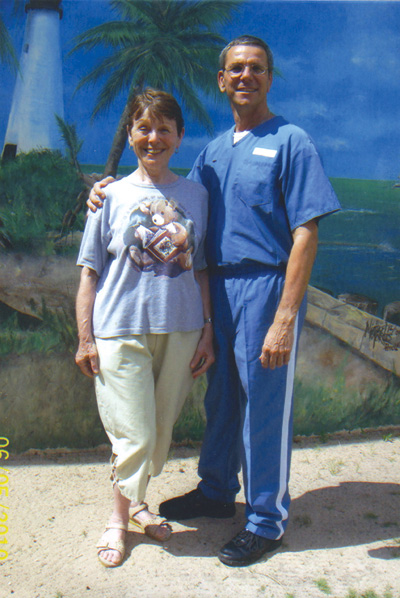

PAT IS A PETITE FORMER UNITED Airlines flight attendant—once widowed and twice divorced—who lives alone in Virginia, in a big house decorated with teddy bears and wallpaper with pictures of deer. Her office is crowded with files containing Felix’s case documents, and its walls are adorned with photos of him. His only personal possessions, his early photo albums, are displayed on a shelf.

In the early 1990s, after Pat’s second husband died of cancer, she was at loose ends for a time. But she’d found a new calling when a woman in her Bible study “spoke out the message” that the Lord was sending Pat to work among prisoners. She attended one of the weekend trainings of Chuck Colson—the Watergate conspirator turned prison minister—and was soon working for defense lawyers as a liaison to local jails. In October 1996, she received a package from an inmate who was helping Felix with sign interpretation. It included court documents and a draft motion by a fellow prisoner hoping to reverse Felix’s conviction.

Reading over the papers, “I was appalled at the injustice,” Pat recalls. “I felt I had to do something.” Before long, she was preparing motions aimed at overturning Felix’s conviction on the grounds that he couldn’t understand the testimony at his own trial. But it turned out Florida law gives inmates only two years to file such motions, and Felix was nearly 12 years past that deadline. He also missed the cutoff for filing a federal habeas petition.

When his motion was denied, Felix “sat there in that box,” Pat tells me tearfully as we sit on her living room sofa. “He was shackled. And he mouthed to me, ‘Why? I am innocent.'” She continues: “I went to the jail after that and I told him, ‘Felix, I am sticking with you till the very end. I will be that mother you don’t have, that sister you don’t have.’ And he’s called me Mom ever since.”

Laura Rovner, a former staff attorney with the National Association of the Deaf (NAD), told me Felix might have convinced a judge to toss his conviction were it not for the missed filing deadlines. After all, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 mandates that any entity receiving federal money have an effective communications system for the deaf, and the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) specifically requires state and local agencies to make sure a disabled person can communicate as effectively as anyone else. “It is hard to think of a situation where that is more critical than where somebody is being tried for a serious crime,” Rovner says.

But institutions of justice “frequently do not honor the letter and spirit” of these laws, says Howard Rosenblum, who heads the NAD. “The challenge has been to actually litigate against every law enforcement agency, lawyer, court, and prison that violate the requirements.” The Justice Department could force state and federal prisons to comply, Rosenblum adds, but it has failed to do so. (The DOJ didn’t respond to my requests for comment.)

As a result, disabled people who land in the slammer face what David Fathi, head of the ACLU’s National Prison Project, calls “a nightmare of vulnerability, abuse, and exclusion from the most basic prison programs and services,” adding, “I think prisoners who are deaf or blind are often the worst off of all.”

Specifically, Rosenblum says, deaf and hard-of-hearing inmates are often “unable to understand instructions of guards, to take classes that make them eligible for early release, to learn skills, to know when meals are announced, to know when visitors are here to see them, to watch television, to use the telephone, to express grievances, to communicate with counselors or doctors, and to defend against claims of misconduct.”

Jack Cowley, a former Oklahoma warden who serves on the advisory board of the National Institute of Corrections (which provides federal support to corrections agencies) tends to agree. While most prison officials would say, “‘Oh, yes, we make accommodation,'” he says, “there is still this sort of deliberate indifference when it comes to back in the cellblocks.” Most state facilities, Cowley adds, try to house their deaf inmates together for mutual support, “and hopefully some staff member will find some compassion and look after them.” But “there’s not a lot of sympathy in the halls.”

In 2003, Pat approached the Florida courts with fresh evidence: an affidavit from Frank, who, apparently feeling remorseful, conceded that Felix was innocent. Felix had received it back in 1989 and given it to a jailhouse law clerk, who misfiled it as a habeas petition. When it was returned for refiling, Felix, flummoxed by the legal jargon, thought he’d been denied. Pat only discovered the affidavit years later while going through Felix’s papers.

Frank became the star witness at an evidentiary hearing the court ï¬nally granted in 2006, after a three-year delay. Pat had collected affidavits from five inmates who’d known Frank at various prisons. All swore that Frank had told them he’d pinned the killing on his kid brother in the hope of sidestepping death row. On the witness stand, Frank admitted the same: “He had nothing to do with it,” he testified. “It was me and Raymond Stanley that did it.”

Nearly a year later, the judge denied Felix’s motion for retrial or release, saying he couldn’t discern what was true.

ON A SUNNY SUMMER morning, after driving all the way from Virginia to Florida the previous day, Pat picks me up at the Jacksonville airport in her red Nissan Xterra. Our destination is the Jefferson Correctional Institution, two hours due west, a cluster of unremarkable sand-colored structures with dark, slanted roofs. When we arrive, an officer escorts us to a building where an assistant warden offers up his office for my interview with Felix. About 10 feet off stands a man with short salt-and-pepper hair. “Hi, Felix,” I call out, before reminding myself aloud, “Oh, right, he can’t hear me.”

“Oh, Garcia?” says the warden. “He can hear.”

In fact, the prison’s medical staff has deemed Felix profoundly deaf, with hearing loss exceeding 90 decibels. So he can hear, in some muffled fashion, the sound of a car horn, a Harley-Davidson, or a jet taking off, but not human voices. His prison-issued hearing aid merely amplifies the institutional din, Felix says. But because he tries so hard to accommodate and understand, guards think he hears more than he lets on.

Pat Bliss and Felix at Polk Correctional institution, June 5, 2010 Courtesy Pat Bliss.

Pat Bliss and Felix at Polk Correctional institution, June 5, 2010 Courtesy Pat Bliss.

Behind his round glasses, Felix’s face is gaunt but expressive, and his voice contains a note of desperation. He speaks and signs simultaneously, with Pat acting as our mutual translator. Felix explains that his situation has been getting worse. He was removed from a prison where he had a small community of deaf acquaintances and sent to a series of other facilities before landing here. Shortly before the move, he’d seen his daughter, now 30, for the first time since she was six months old—she lives in Florida, but too far away to visit regularly. At Jefferson, he’s housed apart from other deaf prisoners and lacks access to sign language interpreters. He lives in fear of offending fellow inmates by inadvertently ignoring them; shortly after arriving here he got into a fight and ended up in solitary.

I ask him about the rape. It happened in December 2010, he says, when two men assaulted him in a shower at the Department of Corrections’ Reception and Medical Center in Lake Butler. He reported it and for weeks afterward spent hours each day crouching in terror against his cell door, trying to decipher noises that might announce another would-be assailant. He was later transferred to the Madison Correctional Institution, where he attempted to hang himself with a sheet. The staff put him on suicide watch, Felix says, leaving him naked in a cell for six days. (Suicidal inmates, clarifies a prison official, are clad in a nonflammable, untearable paper “shroud.”)

In theory, Felix could file a civil rights lawsuit, but the Clinton-era Prison Litigation Reform Act makes it extraordinarily difficult for individual prisoners to bring a federal case. Class actions in New York and Virginia have resulted in somewhat improved services for deaf prisoners in those states, and there are suits pending against the Illinois corrections department and the federal Bureau of Prisons. A Florida lawsuit aimed at winning deaf inmates access to a device that would let them watch TV was tossed recently after prison officials argued that there were not enough plaintiffs to justify a class action. (In a deposition, an ADA compliance officer for the Department of Corrections admitted she had no idea how many deaf prisoners there were in the system; a DOC spokeswoman later told me that only 74 inmates were receiving services.)

Beyond trying to improve Felix’s lot in prison, Pat concedes, few options remain. She’s exhausted every angle in his criminal case. In theory, Gov. Rick Scott could grant him a pardon, but Scott, a tea party champion elected in 2010, has generally moved to make the clemency process more arduous. Felix will be eligible for parole in 2024, at age 62, but even then his odds will be abysmal. Only 50 Florida prisoners were paroled last year; in fact, the state eliminated parole for virtually all new convictions in 1995.

A few months after our interview, Felix was moved again, this time to Tomoka Correctional Institution, where there are deaf inmates and some programs available. He’s less isolated now but only slightly less fearful. “Many, many times, deaf people raped and beat and no help from the officers,” Felix wrote in a letter to McCay Vernon. “Many times I just want to die but have Jesus in heart…Pray every day to help other deaf.”