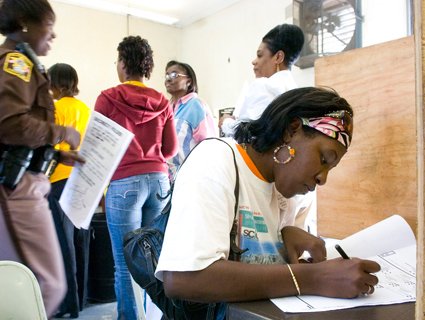

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/calliope/291772635/sizes/z/in/photostream/">muffet</a>/Flickr

Republicans in state legislatures across the country have spent the past year mounting an all-out assault on voting rights, pushing a slew of voter ID and redistricting measures that are widely expected to dilute the power of minority and low-income voters in next November’s elections. Now that effort has come to Capitol Hill, where the House* will vote Thursday on a GOP-backed bill to eviscerate the Election Assistance Commission (EAC)—the last line of defense against fraud and tampering in electronic voting systems around the country.

[UPDATE: The bill passed 235-190 on a mostly party-line vote.]

The EAC was created in the wake of 2000’s controversial presidential election as a means of improving the quality standards for electronic voting systems. Its four commissioners (two Republicans and two Democrats) are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. The commission tests voting equipment for states and localities, distributes grants to help improve voting standards, and offers helpful guidance on proofing ballots to some 4,600 local election jurisdictions. It also collects information on overseas and military voters and tracks the return rate for absentee ballots sent to these voters.

On Friday, a House subcommittee on elections will vote on Rep. Gregg Harper’s (R-Miss.) bill eliminating the EAC along with the longstanding public financing system for presidential campaigns. Republicans claim that the commission has already achieved its aim of cleaning up elections. Its responsibilities, they argue, can be reabsorbed by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), which oversaw voting machine certification prior to the EAC’s creation in 2002. Ending the EAC, Republicans estimate, will save $33 million over the next five years.

Good-government groups, including the Campaign Legal Center, the League of Women Voters, and People for the American Way, have leaped to the commission’s defense, arguing that eliminating it would pose a “threat to the health of our democracy and yet another distraction from the vital and unfinished business before the House.”

Democrats have argued that eliminating the EAC will shift the cost of administering elections to state and local governments at a time they can least afford it. Having the FEC, which oversees campaign spending, handle voting machine certification precipitated the Florida recount in 2000. That debacle led directly to the EAC’s creation in the first place. “I…do not want to see another fiasco like what we endured in 2000,” wrote Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.) in a statement denouncing the move. “It seems Republicans are more interested in keeping people from the polls than protecting the right to vote.”

While Republicans want to kill the EAC, election security experts like the Brennan Center for Justice’s Larry Norden advocate its expansion. Last year, he wrote a report listing roughly 200 cases of inaccurate vote tallies and other problems attributed to voting systems dating back to 2002. In many of the cases Norden examined, voting machine vendors like Hart InterCivic and big-time player Election Systems & Software (ES&S) blamed the mistakes on election officials rather than their machines.

During a primary election in May 2010 in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, for instance, roughly 10 percent of new ES&S machines froze up. While ES&S officials blamed county election officials, similar problems surfaced with the same model of machines in Florida. This past March, ES&S senior vice president of systems Ken Carbullido told a congressional committee that ES&S had fixed the bug. “While we may respectfully disagree with the EAC on the length of time that transpired in moving these corrections through the process, and while we may disagree with their decision to seek a formal investigation, we cannot overemphasize our willingness to be part of this program,” Carbullido said.

Just five days later, though, the commission fired back, saying in a statement that ES&S hadn’t fixed the “anomalies” in the system in question. “EAC eagerly awaits the submission of this information by ES&S so it can be tested, certified, and installed in the field to make sure that it will address and solve the issues,” the commissioners wrote in the statement.

“This is where having a national agency like the EAC to publicize these problems to all local election officials, and to force the vendors to deal with these problems as quickly a possible, is…important,” the Brennan Center’s Norden argues. Primary election snafus “may not sound that major. But on Election Day, having the machines freeze could be a disaster.”

Because regulations for voting machines vary greatly from state to state—some require that their election must be EAC-certified, while others ignore federal guidelines altogether—Norden recommends empowering the EAC to create a national database for election equipment makers. The database would offer guidelines to standardize voting machines across the country and keep tabs on the billions of dollars that have been spent by federal and local governments on new voting equipment over the past several years.

Critics have charged the EAC with exaggerating concerns over voter fraud, underplaying charges of voter discrimination, and being swayed by political influence from both parties. Richard Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California-Irvine, says that the EAC has never quite lived up to its promise. “There were a few commissioners early on who tried to make the agency into a more relevant player, but they failed and the agency became mired not only in the voting wars between Democrats and Republicans over voter fraud,” Hasen says. “It also became the target for extinction by state and local election officials who feared for any encroachment on their turf.”

But Hasen adds that the EAC has still played a key role as a clearinghouse for information on voter technology issues. Its elimination would “mark a defeat for efforts at greater centralization and rationalization of our election processes.”

While the EAC may still be working out its own problems, Norden says that it’s nowhere near as dysfunctional as the perpetually deadlocked FEC: “The public would lose an agency that—after years of building up its expertise—for all its flaws is actually functioning and regulating voting systems. They would lose that, and that’s a dangerous thing.”

Previous efforts to quash the commission haven’t gone as planned. In June, the House rejected a bill to end the EAC. Undeterred, House Republicans again targeted the EAC for destruction in October, recommending that its funding be eliminated as part of the congressional supercommittee’s effort to cut $1.2 trillion in government spending. For now, the EAC plans to continue moving forward with preparations for 2012 “until someone shuts the doors or tells us to stop,” says Jeannie Layson, a spokeswoman for the commission.

Ultimately, money could determine whether or not the lights stay on at the EAC. Between 2000 and 2004, ES&S spent nearly $300,000 lobbying Congress; so far in 2011, it has spent $15,000. In October, it retained the services of Russ Klenet and Associates, a prominent Washington lobbying firm. Vendors like ES&S have a vested interest in preventing a regulatory body like the EAC from evaluating their systems—regulatory scrutiny makes it harder for them to market and sell their equipment to elections commissions around the country. (ES&S did not respond to a request for comment.)

But if the GOP’s EAC demolition plan gets through Congress, it could give ES&S and companies like it free rein to run roughshod over accountability standards.

“Given that we are seeing this war on voting around the country,” Norden says, “it would be a terrible message that Congress would be sending to get rid of the one federal agency left to make sure our elections are actually working.”

*Correction: The story originally said that a congressional committee would be taking up the bill.