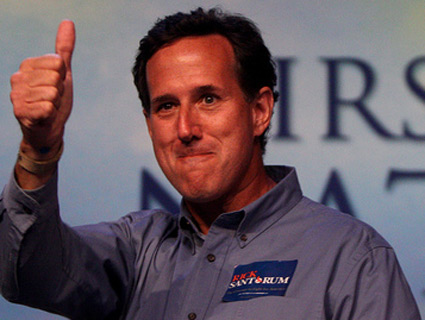

2012 GOP presidential candidate Rick Santorum<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/22007612@N05/6236330273/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

Rick Santorum wants the government out of every aspect of Americans’ lives—especially the housing market. He pledges to eliminate Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the twin government housing giants that help guarantee 90 percent of all new mortgages in America. He wants to “let capitalism work” and allow the housing market to “find its bottom.” Only then, he says, will the recovery begin. It’s a plan that would make Adam Smith proud.

Yet Santorum wasn’t always so opposed to government intervention in housing. In a deal that’s gone unreported during his presidential run, Santorum bought his first house in 1983 with a cut-rate government-backed mortgage, according to records compiled by the campaign of Sen. Harris Wofford (D-Penn.), who Santorum defeated in 1994. He received his loan through a state program to boost homeownership among low- and middle-income families. Santorum, in other words, benefited from a program whose mission mirrored that of Fannie and Freddie, the companies he now rails against and wants to dissolve. (Santorum spokesman Hogan Gidley did not respond to a request for comment.)

Santorum, then a law student and a Pennsylvania state Senate aide, landed the mortgage through a program run by the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA). He used the $41,600 loan to buy and renovate a three-story brick house in Harrisburg, the state capital. According to a 1994 Philadelphia Inquirer story, the interest rate on the government-backed mortgage was 13.08 percent—more than 3 percentage points lower than the market rate at the time.

The PHFA’s loan program was the first of its kind in the state. State bonds backstopped the mortgages, only lenders approved by Fannie and Freddie could issue them, and families earning more than $35,000 did not qualify, according to PHFA records. (Santorum’s income totaled $27,000 the year he got the loan.) The loan’s promise of a low, fixed interest rate was so enticing to working and middle class homebuyers that, as the Inquirer noted, the PHFA’s board decided not to publicize the program, fearing a “potential problem” like a mad rush on the day the loans were made available.

Despite the lack of publicity, Pennsylvanians camped out overnight in lawn chairs in hopes of getting cheap PHFA mortgages. Only a limited number were made available and they went fast. But Santorum managed to snag one. The Wofford records, which contain opposition research on Santorum, suggest that Santorum potentially got his discounted PHFA loan via “political favors,” or that his state senate job “could have tipped him off early” to the program. When asked about his loan by the Inquirer, he told the paper he’d heard about the government-backed mortgage program through his job in the state senate. But, he added, “I can guarantee you I got no special treatment.”

His discount Pennsylvania loan wasn’t the only time Santorum has been accused of receiving special treatment on a mortgage. As the American Prospect reported in 2006, Santorum secured a $500,000 mortgage from a private investment firm called Philadelphia Trust Company, even though he didn’t meet the firm’s loan criteria. Company brass had donated $24,000 to Santorum PACs and the bank’s CEO, Michael Crofton, chaired a charity of Santorum’s.

At the time he got the Philadelphia Trust loan, Santorum was a rising Republican Senator on the banking committee, giving him oversight of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Santorum knew the mission of the companies well, if only because the PHFA program he benefited from decades earlier aligned with one of the central reasons Fannie and Freddie exist in the first place: to help low- and middle-income families buy homes. In the case of Fannie and Freddie, the two companies don’t issue loans but instead buy up mortgages by the millions in order to free up lenders to make loans to new homeowners.

For much of his Senate career, Santorum supported Fannie and Freddie in this mission. He even argued for more government involvement in boosting homeownership among low- and middle-income Americans. In a 2000 law review article, he said “compassionate conservatism” must include new government policies to “lift greater numbers of the disenfranchised out of poverty.” Chief among those, he went on, was “access to safe and affordable housing,” including homeownership and renting.

In a July 2005 Senate banking committee hearing about imposing more regulation on Fannie and Freddie, Santorum said the two companies should be reformed with an eye “toward taking a more active role in creating housing opportunities for low and moderate income families.” And in the mid-2000s, Santorum also backed the Community Development Homeownership Tax Credit Act, which would have spurred the building and renovating of new homes for disadvantaged families. Fannie and Freddie backed the measure, but it never became law.

Now, Santorum slams those same pro-homeownership policies as drivers of the mid-2000s housing bubble and the market meltdown that ensued. “Part of it was government regulation and government markets that caused the bubble, and that caused the loose lending practices that led to the problems,” Santorum told MSNBC’s Ed Schultz last fall.

On the campaign trail, Santorum says he’s the lone candidate “who, throughout [his] career, has not only checked the box on conservative issues but has fought for conservative issues.” When it comes to government and the housing market, he has checked a few liberal boxes as well. And as his 1983 mortgage deal shows, Santorum didn’t let his conservative beliefs get in the way of a good deal.