Hardy Jones (kneeling) and Dr. Carlos Yaipen Llanos (right) with a dead dolphin on Peru’s northern coast Courtesy BlueVoice.org

Something awful is happening in the waters off Peru’s northern coast, where some 3,000 dolphins have died and washed ashore since January. This rates as one of the worst, if not the worst, Unusual Mortality Event (UME) ever recorded.

(I’ve been writing about the UME with marine mammals in the Gulf of Mexico since BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster here and here and here.)

In recent weeks more than 1,200 dead seabirds, mostly pelicans, have washed up along the same Peruvian beaches. And Saturday the government declared a health alert along Peru’s northern coastline, urging residents and tourists to stay away from the beach while it investigates the unexplained deaths. It also warned local officials to wear protective gear when handling dead birds and animals.

So what’s going on?

Credit: monkey sidekick via Flickr

Credit: monkey sidekick via Flickr

My friend Hardy Jones of Bluevoice.org visited Peru in late March, where he joined a crew mustered by veterinarian Dr. Carlos Yaipen Llanos, the Lima-based director of the marine mammal rescue organization ORCA Peru. In one day they counted 615 dolphin carcasses scattered over 84 miles of coast before the high tide swept them off the beach.

Two species were hit: common dolphins (both genders, all ages) and Burmeister’s porpoises (only females and calves). As Jones wrote at his blog, BlueVoice Views:

At 11am we packed into a four wheel drive Toyota pickup with a back seat cab and drove through San Jose to the beach, cranked a right turn and headed north at low tide on a beach that was mostly firm…Within a few hundred yards we began to see dead dolphins. In ones and twos, then Carlos saw a Burmeister’s Porpoise. Some were highly decomposed while others were in the surfline freshly stranded. All were dead.

Yaipen Llanos performed beach necropsies and summarized his findings:

Macroscopic findings include: hemorrhagic lesions in the middle including the acoustic chamber, fractures in the periotic bones, bubbles in blood filling liver and kidneys (animals were diving, so the main organs were congested), lesion in the lungs compatible with pulmonary emphysema, sponge-like liver. So far we have 12 periotic samples from different animals, all with different degree of fractures and 80% of them with fracture in the right periotic bones, compatible with acoustic impact and decompression syndrome…

At this point, the evidence points towards acoustic impact and decompression syndrome. However, the large aggregation of dolphins is leading towards a potential epidemic outbreak of morbillivirus, brucella or both. We have recorded morbillivirus in South American sea-lions and the Peruvian population of common dolphins is a migratory part of that at Costa Rica, so chances are high. Also, evidence of previous mass stranding of this magnitude was associated to morbillivirus outbreak in Europe during the 90’s also in common dolphins and porpoises.

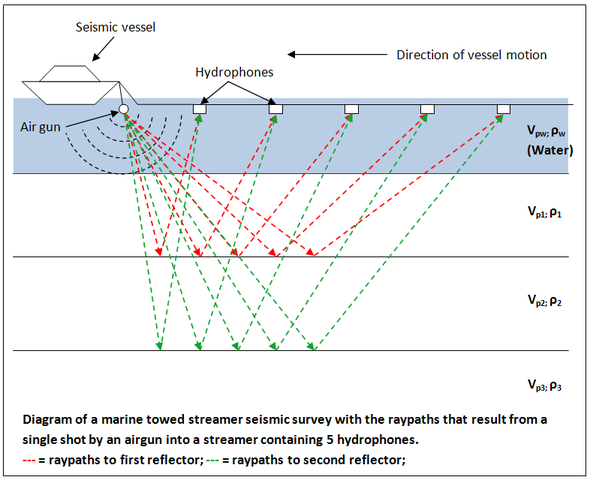

Schematic of a marine seismic survey Credit: Nwhit via Wikimedia Commons

Schematic of a marine seismic survey Credit: Nwhit via Wikimedia Commons

The worry about acoustic impact injuries and accompanying decompression syndrome is that offshore seismic testing by the oil and gas industry may be killing dolphins. Houston’s BPZ Energy has exclusive license contracts over 2.2 million acres in four blocks in northwest Peru, including offshore. They issued this statement on April 11, in which they don’t actually say much:

BPZ Energy, an independent oil and gas exploration and production company, today issued clarifying comments as a result of recent inquiries received regarding its offshore seismic activity and its possible relation to reported dolphin deaths in Peru. The Company also reaffirmed its commitment to good corporate citizenship in all matters, including social, community and environmental affairs. BPZ Energy operations in Tumbes are located 500 km north of Lambayeque where dolphin deaths have been reported.

It’s possible the dolphins and pelicans have been killed by different problems. Take your pick: In the case of dolphins, acoustic impact or disease outbreak (though officials have recently denied morbillivirus); in the case of the pelicans, some suggest starvation.

That’s because a massive pelican die-off occurred in the same area in 1997, due to a strong El Niño event in the Pacific, when anchovies migrated away from the coast and birds starved. Except there’s no El Niño underway just now, only the end of a La Niña event and a return to neutral ocean conditions, according to the Climate Prediction Center.

As with so many mass die-offs in the ocean, we may never know.